Balancing the need of high material availability with low inventory is tricky. Pull systems are a very good way to achieve this. But sometimes people argue with me that planning can be better if you use all the available information to create a production plan which then outperforms a pull system. In theory, this could work, but in practice it rarely does. After all, that is what conventional push systems are trying to achieve, usually with mediocre results. Let’s have a look.

Balancing the need of high material availability with low inventory is tricky. Pull systems are a very good way to achieve this. But sometimes people argue with me that planning can be better if you use all the available information to create a production plan which then outperforms a pull system. In theory, this could work, but in practice it rarely does. After all, that is what conventional push systems are trying to achieve, usually with mediocre results. Let’s have a look.

Introduction

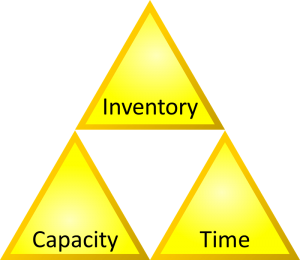

The reason that we need inventory is primarily to decouple fluctuations. Other ways to decouple fluctuations are adjusting capacity (tough to do on short notice) and waiting (which always works, but often it is least desirable to let the customer wait). Often, inventory is simply the best choice to decouple short-term fluctuations. Of course, even better but much harder is to reduce fluctuations so you don’t have to decouple them afterward.

Your production system is also a potential cause of fluctuations. Leveling aims to reduce these fluctuations. However, breakdowns and other disruptions increase fluctuations. A bad production program can also increase fluctuations. In theory, there is another option to handle fluctuations: You could just run your production system in sync with the fluctuations.

For example, if your customer requires more products, you would not need inventory if you just happened to produce more of these products. If your customer requires less, you would not increase inventory if you just happened to produce less of this product. If the output of your production system is perfectly synced with the demand, you would not need any inventory and would still achieve 100% material availability.

If you are in production, you probably already see a lot of holes with this plan. I agree on this. But, just for the sake of understanding, let’s have a look at what would be necessary to make this perfectly synced production system a reality, and why it is not possible, or at least is possible only in a limited way.

The All-Knowing Production Planner

In theory you can imagine (or dream) of a perfectly synced production system, where each produced item would perfectly match the customer demand. One possibility would be a system where there are no fluctuations at all… which is a fallacy. In reality, every production system fluctuates, some more, some even more, and some even much more.

Another purely theoretical option would be to know all fluctuations beforehand and plan around them. You would know for every part sold when the customer would order it, you would know all machine breakdowns, all supplier delays, and anything that will happen on your shop floor way before it happens.

Another purely theoretical option would be to know all fluctuations beforehand and plan around them. You would know for every part sold when the customer would order it, you would know all machine breakdowns, all supplier delays, and anything that will happen on your shop floor way before it happens.

In this case, you could include all fluctuations in the production plan, ensuring that a part is completed exactly when you need it, not earlier or later. Inventory would only exist to be worked on, or if you decide to go for larger batches (i.e., you would not order every screw separately, but a box of 500 when you need the first screw, or you may have larger lot sizes due to changeover times).

Obviously, knowing all fluctuations beforehand is impossible. You are not an all-knowing god on the shop floor, and some fluctuations you simply do not know beforehand.

Foreseeable and Unforeseeable Fluctuations

Some fluctuations you know beforehand, others only after they hit you, and some you may not even notice. With some effort you can predict maybe a few more fluctuations, but it is impossible to know them all. The question is: Can you use your knowledge of foreseeable fluctuations to reduce the inventory level and produce closer to the customer demand, even if it is not perfect?

This is possible, albeit with limitations. It is done frequently, with a common example being seasonality. Seasonality is often decoupled by increasing and decreasing capacity. You can also decouple seasonality by increasing and decreasing demand (e.g., if you are using pull systems, increase the inventory target or the number of kanbans before the season, and reduce afterward). If you are working in production, I am pretty sure you have done something like this. Similar build-ups of inventory are also common for larger maintenance shutdowns, replacement of machines, or other foreseeable and major fluctuations.

And this brings me to a key point: Besides being foreseeable, these fluctuations are major. What about doing the same thing for smaller fluctuations by adjusting the production plan and capacity to have inventory for these smaller fluctuations? Sounds too nice to be true, right?

It is too nice to be true. While it is possible in theory, it quickly becomes more and more work for the planning. Instead of doing this two (seasonality) or three times (maintenance) for a product or line per year, you would have to do this weekly or even daily. This would be a lot of effort. Few planning departments would be prepared for this enormous increase in workload. In the extreme case, every product would be make-to-order for the predicted customer demand. This would be an immense workload. And you still would have to deal with the unforeseeable fluctuations. At one point, the reduction in inventory would simply no longer be worth the effort to do so.

It is too nice to be true. While it is possible in theory, it quickly becomes more and more work for the planning. Instead of doing this two (seasonality) or three times (maintenance) for a product or line per year, you would have to do this weekly or even daily. This would be a lot of effort. Few planning departments would be prepared for this enormous increase in workload. In the extreme case, every product would be make-to-order for the predicted customer demand. This would be an immense workload. And you still would have to deal with the unforeseeable fluctuations. At one point, the reduction in inventory would simply no longer be worth the effort to do so.

Many ERP push systems try to calculate the schedule on the best available data, but still need safety buffers (time or inventory) for unforeseen fluctuations. Despite all that, they usually perform worse than pull systems. If you would try it, you would end up with a push system, having lots of work, and the unforeseeable fluctuations would still mess things up significantly (especially for job shops, where small fluctuations can have an enormous impact on the lead time).

If You Do It, Do It with Pull

There is one way out of this, which could be a good compromise between workload and impact. You do it with a pull system. A make-to-stock pull system is an (almost) automatic system to refill your inventory to the target level. The only thing you adjust periodically is the inventory level.

Well… adjust more often. Foreseeable fluctuations can be handled by increasing and decreasing the inventory level in your pull system. Increase or decrease the number of kanban to match the expected fluctuations. But again, this is not easy. If your pull systems are quite new, then put your effort on improving the stability of the pull system. Adjust only infrequently (maybe every quarter, or only twice per year for seasonality), even if you may have a sliver more inventory than bare-bones necessary. Because frequent adjustments of the inventory level are still quite a bit of work, albeit probably easier and definitely more stable than scheduling every single product.

If you have the planning capacity for more frequent adjustments, you could adjust more frequently. Or, you could put the effort into reducing fluctuations! Rather than addressing the symptoms by planning with the fluctuations, you could address the root cause and reduce fluctuations! Overall, I am not always convinced that a higher planning effort is worth a small reduction in inventory, but of course it depends on the details of your industry.

If you have the planning capacity for more frequent adjustments, you could adjust more frequently. Or, you could put the effort into reducing fluctuations! Rather than addressing the symptoms by planning with the fluctuations, you could address the root cause and reduce fluctuations! Overall, I am not always convinced that a higher planning effort is worth a small reduction in inventory, but of course it depends on the details of your industry.

Summary

Sometimes software tools are sold with the promise to plan around the fluctuations. I believe this is an enormous effort and nevertheless has a high risk of stock-outs. If you really want to adjust to fluctuations, don’t do it for every part, but for short periods by adjusting the inventory limit of your pull system. This will be much easier and much more stable. But if you can, put your effort into reducing the fluctuations rather than managing them. Now, go out, reduce your fluctuations, or let your pull system take care of them if you are short on time, and organize your industry!

Great that you touch this theme.

In my earlier carreer being a Director Operations, my planning department was in charge of analysing daily what has happend a day, sometimes half a day before. With approx 10.000 end items we manufactured, we have been responsible for the european central warehouse (only our products) as well intercompany orders from the US plus OEM orders. Every day we started aprox 100 workorders and had always between 500 and 1.000 work orders on the floor.

We had installed a forecast analyst who tracked the whole day incoming orders against their original forecast as well our own production plan. For all orders which were not in line with their forecast and outside our own runrates we (the planning team- not sales or productmanagement) contacted immediately the customers (in our case the different country managers in the world) and asked if this demand is a new client they have or a campaigne they are running or why this unusual order came up. Depending on the response, we changed asap our parameters and sometimes started building a small stock for the central warehouse to cover future demands.

Sure this was an additional position in the planning team but the pay off was incredible as we generally could deliver 95 % of orders within a day.

Hello Gerhard, Thanks for the war stroy from the front line. I guess it was a tough sell for accounting, which probably calculated the cost of the forecast analyst, but cannot really calculate the benefit (and hence set it to zero).

Toyota has lots of people to help with all kind of improvements, more than most western companies.

Great article, after working in a large warehouse this summer that used a pull system, it was clear that with a better thought out plan, the system could be improved. Often times by failing to do proper forecasting, certain items were running out quickly while others were failing to move off of the shelves at all. It is certainly interesting to look at the idea of adjusting production capacity to best match customer demand, but as said in the article this is extremely hard to interpret. It is also important to state that many companies do not manufacture their own products and instead are buying and reselling the end customers. This means they have no way of adjusting their production capacity; however, they are still able to adjust their future orders.

Hello Tim, I think Pull is already pretty good. A plan (i.e. push) could be better, but it is a LOT of work, and if you mess up it will be (much?) worse.

I always enjoy reading your insight into these topics! My favorite part of today’s is that you point out that nothing can really ever be perfectly planned or executed throughout a production system. The reality that all systems fluctuate in some manner is just a matter of fact. Companies that have an easily adjustable system I would agree have a better chance at fixing issues that occur as they happen therefore leading there to be less fluctuation throughout.

Ellen, yes, that is unfortunately a common mistake of many ERP programs, where the solution in theory is perfect, but in practice something changes and it falls apart like a house of cards.

Great article Chris! I know firsthand how introducing a finished goods buffer between production and delivery can reduce the noise significantly. The production can produce to replenish the goods based on consumption, while the consumption data along with forecast data can guide the setting up of the buffer levels of the finished goods.

Lakshmi, Many thanks for the confirmation from the front lines 🙂

Great Article. I like how you noted that nothing can ever be planned or executed perfectly throughout a production system. All systems fluctuate in some way. Companies that can be flexible and have an easily adjustable system would have a better chance at fixing problems and compensating for other issues as they come along.

I know only three things for sure

– Every day I have to make a lot of choices

– Some time in the future my life will end

– All plans are wrong

The third one will need inventories. The size will depend on the fluctuations that cause problems in the factory.

Excellent article.

Virtually all ERP/APS systems are push – they can only handle one independent inventory position and the rest of the BOM is dependent demand. The only attempt to rectify this (ie. provide software that is specifically designed to enable pull replenishment across multiple echelons) is Demand Driven MRP – one of the earliest whitepapers from the Demand Driven Institute was actually called “Lean finds a friend in DDMRP” Given that nearly all manufacturing companies use some form of ERP, their attempts at Lean have rarely included ‘end-to end’ pull unless they’ve tried desperately to, very expensively, ‘frig’ the system and almost always failed / got something inadequate – I’ve seen a few!

ERP has been a major hindrance to full Lean implementations for this reason but since DDMRP appeared SAP and MS Dynamics have invested / made it available through their ERP to the satisfaction of DDI as have a host of other software providers.

As ever with innovations there are some who still say that DDMRP isn’t really Lean – well its not! Its “merely” a software designed to enable multi-echelon pull in manufacturing / distribution companies and provides such functionality as inventory position(s) location support, inventory position(s) target sizing, ROP/ROC and concurrent planning (ie. forecast-driven capacity planning alongside the the pull replenishment). As such it helps companies overcome their biggest Lean blocker which is their ERP system!

Sorry for the “commercial” but Lean needs all the support it can get as manufacturing companies feel they have to jump on the ‘digitalisation’ band wagon prevent them and wasting $Ms on AI powered push-MRP