This post of this series on standards looks at how to use the standard correctly, and how to improve a standard. Hint: It is all about the people actually using the standard. This series is again getting longer than I thought, as there is much detail to be discussed. The next post will finally look more at standardized work.

This post of this series on standards looks at how to use the standard correctly, and how to improve a standard. Hint: It is all about the people actually using the standard. This series is again getting longer than I thought, as there is much detail to be discussed. The next post will finally look more at standardized work.

Document the Standard

The last step (excluding of course the always present improvement activities) is to document the new standard. Naturally, there will be a file somewhere on your hard disk or server, and probably some entries in the list of standards that your company has, including the release date, the version number, etc. This is one of the very few steps in the creation of a standard where you may not need the frontline operators that later have to work with the standard.

Put the Standard Near the Corresponding Workplace

However, the completed standard should additionally also be in printed form at the location where it is used. These are commonly folders (either ring binders or merely a box with laminated cards) that are placed close to the workspace. I have also seen the standard displayed on a monitor. Either way is fine. This way you can display the currently valid standard (e.g., for the current part in production).

Put Up the Standard for the Worker

The current standard should also be displayed out of the box. Overall, there are two possible approaches for displaying the standard.

The current standard should also be displayed out of the box. Overall, there are two possible approaches for displaying the standard.

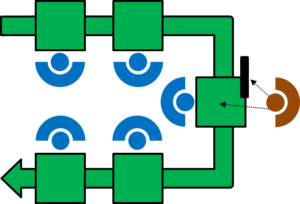

If the standard is used infrequently with long breaks between the standards, the operators can use the standards as a guide to jog their memory. For example, if there is an exotic product that is done only a few times per year, the operators may not remember the standard well. In this case, the standard should be taken out of a folder or box close to the workstation and put on the workstation so that the operator can see them. Alternatively, there can be a monitor displaying the current standard to be used for the operations. The operator then can look up at the standard whenever there is something unclear.

Put Up the Standard for the Manager

If the standard is used very frequently and highly repetitive with short cycle times, then the operators will quickly know the standard by heart. If an operator assembles a mobile phone every 60 seconds, they do not need to see the standard but have memorized the steps very well. The operators probably even dream of assembling mobile phones. In this case, there is no need to put the standard in front of the operator.

If the standard is used very frequently and highly repetitive with short cycle times, then the operators will quickly know the standard by heart. If an operator assembles a mobile phone every 60 seconds, they do not need to see the standard but have memorized the steps very well. The operators probably even dream of assembling mobile phones. In this case, there is no need to put the standard in front of the operator.

However, in this case the standard is primarily for the managers and put up so that the manager can see them. The manager may not have memorized all standards in his area. This way the manager can read the standard while verifying that the operator is actually following the standard. Depending on the layout of the workspace, this may for a U-line even be on the other side of the workplace. The managers stands outside of the U-line and observes the worker while reading the standard. This allows also the manager to verify that the standard is used correctly. Often the needs of the worker and the manager are combined and the standard is put up in a spot where both the manager and the worker can easily see them. (Thanks to Michel Baudin for the good article on this topic.)

Improve the Standard When Needed

Finally, as part of the continuous improvement activities, you should improve the standard. Of course, continuous improvement does not mean that every standard has to be improved all the time. Similar to the creation of the first standard, for the change of an existing standard there should be a (foreseeable) problem or an improvement potential. If the benefit of solving the problem or capturing the potential is worth the effort of doing so, then please do. This again is related to the cost and benefit of an improvement, and where you want to focus your energy on.

Finally, as part of the continuous improvement activities, you should improve the standard. Of course, continuous improvement does not mean that every standard has to be improved all the time. Similar to the creation of the first standard, for the change of an existing standard there should be a (foreseeable) problem or an improvement potential. If the benefit of solving the problem or capturing the potential is worth the effort of doing so, then please do. This again is related to the cost and benefit of an improvement, and where you want to focus your energy on.

All the subsequent steps are also very similar to the creation of the first standard. We select a problem that is relevant, and started a problem-solving team, the size of which may be reflected by the size of a problem. For simple cases it may be merely one or two operators and a supervisor to update their existing standard. For anything but the simplest improvements, an A3 report can help. Analyze the current state, define a goal, do a root cause analysis, develop solutions, and implement the best one. Then you can update the standard. Don’t forget to update the version number too!

However, before you make the standard live, do not forget the Check and Act of the PDCA! Test out the standard, see if it works, improve (or in the worst case, crap the improvement) if it does not work. Only if you are confident that the standard works well should you put the standard live and update or train all the relevant operators.

The Standard is Owned by the Operators

By its nature, the people most familiar with the standard are the people that use the standard regularly. In most cases, they are also the first to see problems or observe improvement potentials.

Now they could start the long trek through hierarchy to get the attention of the shop floor manager, then get his valuable time to start the improvement, and maybe, just maybe, half a year later a standard will come down from management that maybe even fixes the problem that they wanted to fix. Sounds familiar? Yeah, this is not good.

For many standards it is much easier if the ownership resides on the shop floor. Especially for smaller changes the operators should be able to do it themselves, maybe with a supervisor updating the standard document. Again, make sure that they do the check and act of the PDCA (i.e., they test the standard a few times before going life). If there are multiple shifts, there should also be a coordination between the shifts, otherwise the other shift will be surprised by a new standard that they think may not even work. Trust your employees! Recognize their contribution! If you think there are possible unforeseen consequences where a good change at one location can make lots of problems elsewhere, require management approval of the standard. But again, it is rarely the management that gives the answers and makes the standard. If anything, management must ask the right questions and support the operators to help the workers create a better standard.

In my next post I will look at standardized work (or sometimes also standard work), which is a framework for balancing a line and setting up proper standards. Until then, stay tuned, go out, use your standard, and organize your industry!

Series Overview

- Standards Part 1: What Are Standards?

- Standards Part 2: Why and Where to Do Standards

- Standards Part 3: How to Write a Standard

- Standards Part 4: How to Write a Standard (Continued)

- Standards Part 5: How to Use and Improve a Standard

- Standards Part 6: Standardized Work

- Standards Part 7: How to Write a Work Standard

- Standards Part 8: Example for a Work Standard

- Standards Part 9: Leader Standard Work

Source:

Many thanks to Osamu Higo for writing the excellent article Crucial Misconceptions on Lean – Standardization, which inspired this series of blog posts.

Professor,

It really makes sense that the standards would be a shared resource both for management and for the workers, it can be used for more than one purpose making it even more time effective (for audit and production). By giving the authority to workers to develop standards of work it can help foster an environment of continuous improvement which could lead to better outcomes and better standards all around. Documenting standards is a great way to define workflow and opens the door to measuring, analyzing and improving processes easier in the future.

Thanks