There are different ways to establish a pull system. In my last post I gave an overview of the different types of pull system. Before telling you which one to use when I want to show you the different factors that should go into your decision. What do you have to pay attention to if you want to select a pull system? This post is loosely based on chapter 3.1 of my new book All About Pull Production: Designing, Implementing, and Maintaining Kanban, CONWIP, and other Pull Systems in Lean Production. Let’s have a look:

There are different ways to establish a pull system. In my last post I gave an overview of the different types of pull system. Before telling you which one to use when I want to show you the different factors that should go into your decision. What do you have to pay attention to if you want to select a pull system? This post is loosely based on chapter 3.1 of my new book All About Pull Production: Designing, Implementing, and Maintaining Kanban, CONWIP, and other Pull Systems in Lean Production. Let’s have a look:

This is also a cross-post with the same article on Planet Lean.

Make-to-Stock Versus Make-to-Order

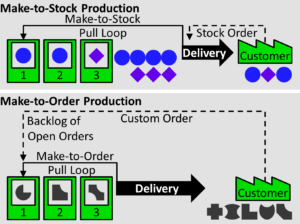

There are different criteria that you have to look at when selecting the flavor of your pull system. The most important criteria is if you produce or ship make-to-stock, or if your product is make-to-order. Was the item produced, transported, or purchased before the customer order, or only after the customer order? High-volume-low-mix and low-volume-high-mix is something very similar, but the key question is still if you aim to always have a product in inventory (make-to-stock), or if you produce only if there is an order and the customer has to wait (make-to-order).

There are different criteria that you have to look at when selecting the flavor of your pull system. The most important criteria is if you produce or ship make-to-stock, or if your product is make-to-order. Was the item produced, transported, or purchased before the customer order, or only after the customer order? High-volume-low-mix and low-volume-high-mix is something very similar, but the key question is still if you aim to always have a product in inventory (make-to-stock), or if you produce only if there is an order and the customer has to wait (make-to-order).

Make-to-stock and make-to-order have VERY different goals. With make-to-stock, the goal is to always have parts available, while requiring as little inventory as possible. You typically produce large quantities of identical products (high-volume-low-mix). The customer order starts a delivery of the item in stock, followed by the replenishment of an identical item. The item was produced in advance, and the customer (ideally) does not have to wait.

With make-to-order, production starts only after a customer order. You usually have a backlog of open orders waiting to enter the pull system. This backlog may also be sequenced according to its priority. Furthermore, a completed part is usually delivered right away after production, and you have little or no finished-goods inventory. Hence, with make-to-order, the goal is to minimize the time between receiving the order and delivering the product, while keeping the system utilization reasonably high. You typically produce many different products in small quantities or even completely unique items (low-volume-high-mix). Only after a customer order does production start. The customer always has to wait for delivery after making an order.

One important effect of this factor on your pull system is the level of detail needed for controlling your pull system. For make-to-order production, it suffices to have only a generic inventory limit across all of your parts within your pull loop. Different parts all contribute to the same inventory limit. For make-to-stock production, however, you have to set a limit separately for every single part type that is in your pull loop.

It is also possible to combine make-to-order and make-to-stock in the same system. In this case, you would need a pull system capable of handling both situations. This mix of make-to-order and make-to-stock is usually a combination of two different pull systems, often kanban and CONWIP. Such combinations of pull systems are absolutely feasible and can handle a mix of make-to-order and make-to-stock production.

It is also possible to combine make-to-order and make-to-stock in the same system. In this case, you would need a pull system capable of handling both situations. This mix of make-to-order and make-to-stock is usually a combination of two different pull systems, often kanban and CONWIP. Such combinations of pull systems are absolutely feasible and can handle a mix of make-to-order and make-to-stock production.

Production/Development Versus Purchasing

A second important distinction is the capacity limitation. Are you producing or developing, or are you purchasing items from an external supplier? This is based on the capacity limit of your system. Can you get all the items you want at once (purchasing), or do you have to do it one at a time (development or production)? Do you have to worry about the production sequence of your items, or is it no problem to just get them all at the same time? In practicality, this is often the difference if you produce or develop items yourself or if you order them from suppliers.

A second important distinction is the capacity limitation. Are you producing or developing, or are you purchasing items from an external supplier? This is based on the capacity limit of your system. Can you get all the items you want at once (purchasing), or do you have to do it one at a time (development or production)? Do you have to worry about the production sequence of your items, or is it no problem to just get them all at the same time? In practicality, this is often the difference if you produce or develop items yourself or if you order them from suppliers.

Production systems usually produce one item after another. Hence the sequence of your orders is relevant. Your production system has a limited capacity, which could be measured in parts per day. If you want to produce too much at the same time, your production system gets clogged up. Some products may be completed early, others may take longer.

However, if you order different goods from different suppliers, you need not think about the sequence of your order. You don’t think if you should order parts A from supplier X first and then parts B from supplier Y. You just order them all at the same time. Even if you order multiple parts from the same supplier, you rarely worry about the sequence of the order. Instead, you let the supplier figure it out.

Flow Shop Versus Job Shop

Another less important factor relevant only to production but not to purchasing is if you have a job shop or a flow shop. Flow shops are much easier to handle. If you can turn your system into a flow shop, it will almost always be beneficial for your system. You only need to control the first process; the others are usually controlled automatically through a FIFO (First-In-First-Out).

If, however, you have a job shop, you need to manage not only what to produce with your system, but have to manage every process in the job shop. POLCA specializes in job shops, but requires more effort because job shops in general require more effort. For mixed systems that have some elements of a flow shop and some elements of a job shop, you may choose which concept fits your system better. Have you arranged your processes in a sequence that fits most products? Then it is probably closer to a flow shop. Were you unable to find a sequence since so many different products have different sequences? Then it is probably closer to a job shop.

High Demand Versus Low Demand

Another smaller factor relevant only for make-to-stock or ship-to-stock is the demand of a particular item. Do you sell large quantities or only a few items? This is also a relative factor. Judging if an item is high demand or low demand is relative to your system. This may also be very different depending on the product type. In particular, it may influence kanban systems to decide what variant of kanban you should use.

Another smaller factor relevant only for make-to-stock or ship-to-stock is the demand of a particular item. Do you sell large quantities or only a few items? This is also a relative factor. Judging if an item is high demand or low demand is relative to your system. This may also be very different depending on the product type. In particular, it may influence kanban systems to decide what variant of kanban you should use.

Small and Cheap Versus Expensive or Large

Finally, a consideration for make-to-stock systems is also the cost and effort of having the item in inventory. Most times, this is based mostly on the value and the size of the item. If the item is expensive, you probably don’t want to tie up too much capital in excess inventory. If the item is large, you probably don’t want to use up too much storage space. In both cases you may invest additional effort to reduce the quantity and hence reduce the tied-up capital or required storage space. For example, if you make cars, you don’t want to put too many expensive and bulky engine drive trains on stock.

If the items are neither large nor expensive, you probably don’t worry too much about your inventory as long as you have enough. In this case, having a bit more material than needed is usually nothing to worry about. Hence, here you may choose a method that may not have the smallest possible inventory limit, but is easier on the management of the pull system.

In my next post I will use this info to give you more guidance on what pull system to use when. Until then, stay tuned, and go out and organize your industry!

Series Overview

- Pull: A Way Forward for Supply Chains – Guest Post by John Shook

- The Different Ways to Establish Pull Production

- What Are the Criteria to Decide on a Pull System?

- Which Pull System Is Right for You?

- What Different Pull Systems Can Be Combined?

Source

This blog post is summarized from my latest book on pull production, where you will find many more details on all of these systems and how they can work together. You will also find a foreword by John Shook.

Roser, Christoph. All About Pull Production: Designing, Implementing, and Maintaining Kanban, CONWIP, and other Pull Systems in Lean Production. 441 pages: AllAboutLean.com Publishing 2021.