Maintenance is good. Maintenance is useful. But like all other tools, the wrong type of maintenance can cause more problems than it wants to solve. Hence, in this post I would like to point out some of the flaws of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM). Don’t get me wrong. TPM is useful and has its strengths, but it also has its weaknesses. You need to know both to use TPM properly. I am looking forward to your input in the comments, as I am sure I will learn something.

Maintenance is good. Maintenance is useful. But like all other tools, the wrong type of maintenance can cause more problems than it wants to solve. Hence, in this post I would like to point out some of the flaws of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM). Don’t get me wrong. TPM is useful and has its strengths, but it also has its weaknesses. You need to know both to use TPM properly. I am looking forward to your input in the comments, as I am sure I will learn something.

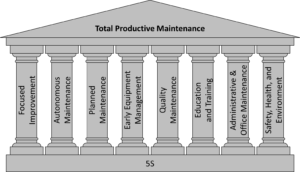

A Brief Critique on the Structure of the Pillars of TPM

Total Productive Maintenance is often based on eight pillars, although some use seven and others use nine, and they are not always the same. Regardless, these pillars contain a lot of good ideas. However, the structure of these pillars is a bit wobbly. Most pillars describe how to do maintenance. However, with the administrative & office maintenance, they stray from the “how to” to the “where.” This would open up another box of topics, which could contain many more areas like logistics, services, healthcare, and so on. Hence, to me it fells like it is either excessive or incomplete.

I would also take 5S out of the foundation, as it is not such a critical method for me. (Useful? Sure! But foundation material? Probably not). Instead, the pillars of focused improvement (or continuous improvement), education and training, and safety, health, and environment are much more overarching, and I would move them into the foundation.

I am also missing the topic of reactive maintenance. What do you do when the machine breaks down? It is supposedly to be part of the Planned maintenance pillar, but often it is not even mentioned, and usually glossed over. I assume the idea is that with preventive maintenance (or planned maintenance, as it is called in the pillars), breakdowns will not happen. However, I believe this is a fallacy. Preventive maintenance can reduce the likelihood of breakdowns, but it is impossible to eliminate all breakdowns. Probably among the best-maintained machines in the world are commercial aircraft, and even so a plane crashes every now and then due to technical problems. This is despite large sums that are put into maintenance of aircraft. However, in most companies the breakdown of equipment does not result in three hundred dead people, and – depending on your company – it may be cheaper to have an occasional breakdown rather than put vast sums into maintenance. Hence, even though it is only after a breakdown, reactive maintenance should also be an important topic in most companies. Besides, even if you miss all other forms of maintenance, reactive maintenance is the default form of maintenance.

TPM often sees itself as the overarching topic in manufacturing, and from the TPM point of view everything else is second to TPM. A similar example would be Total Quality Management (TQM), which often sees everything else as second to TQM. As I am a lean guy, I of course see everything else as second to lean. Well… I am trying not to, but sometimes it slips in. Depending on your view, you can see TPM as a (group of) tool(s) or as the whole toolbox. If you see TPM only as one set of tools, then topics like focused improvement (kaizen), education (standardization), and possibly also quality maintenance would be not part of TPM but part of the bigger toolbox.

Don’t get me wrong. All of these are important topics. Just make sure you don’t do redundant activities. If you already have a good approach toward continuous improvement, do not create a second one just for TPM, but have TPM as part of your overall improvement approach. If you already have a strong quality program, don’t establish a second one with TPM, but have the quality part of TPM as part of your overarching quality efforts. It all depends on which topic is “big” at your company. A quality guy sees quality as the most important aspect of a company. A maintenance guy sees maintenance as the most important aspect. A lean guy like me… is obviously correct and lean is the most important topic in the world </sarcasm>. In any case, make sure neither to overlook these topics nor do them redundantly.

A Better Version of the Pillars?

Just for fun, I created a different house of maintenance. It is loosely based on total productive maintenance, but with quite a bit of reconstruction. Safety (or the pillar for safety, health, and environment) went into the foundation. Similarly, focused improvement was renamed to continuous improvement and also moved into the foundation. Education and training was renamed to standards as the third layer in the foundation. The pillar early maintenance was renamed to design for maintenance, although it is for me a smaller pillar. The pillars of quality maintenance, and administrative maintenance were dropped altogether, since I think that they belong into other houses (e.g., the house of total quality management quality) if you so will. Finally, I added the missing pillar on reactive maintenance.

Just for fun, I created a different house of maintenance. It is loosely based on total productive maintenance, but with quite a bit of reconstruction. Safety (or the pillar for safety, health, and environment) went into the foundation. Similarly, focused improvement was renamed to continuous improvement and also moved into the foundation. Education and training was renamed to standards as the third layer in the foundation. The pillar early maintenance was renamed to design for maintenance, although it is for me a smaller pillar. The pillars of quality maintenance, and administrative maintenance were dropped altogether, since I think that they belong into other houses (e.g., the house of total quality management quality) if you so will. Finally, I added the missing pillar on reactive maintenance.

This is not a variant of the pillars of Total Productive Maintenance, but something different. I am also not a big fan of drawing houses, but maybe it helps you to see which parts I consider important and which ones less so. This house is also not perfect and has for example overlap between preventive/reactive maintenance and autonomous maintenance. Yet, I like it better than the old one. Again, just for fun.

A Warning on Maintenance in General

Maintenance is usually very useful and necessary. But like any tool, it can be used incorrectly. Focusing too much on maintenance runs the risk of neglecting other areas. A more holistic view of the entire system gives a better overall performance, of which maintenance is only one of many aspects. In most companies the risk is more of neglecting maintenance rather than overdoing it. However, there are also examples of doing too much maintenance.

Maintenance is usually very useful and necessary. But like any tool, it can be used incorrectly. Focusing too much on maintenance runs the risk of neglecting other areas. A more holistic view of the entire system gives a better overall performance, of which maintenance is only one of many aspects. In most companies the risk is more of neglecting maintenance rather than overdoing it. However, there are also examples of doing too much maintenance.

For (a slightly older example) example, a detailed analysis by C. H. Waddington found that preventive maintenance itself created unscheduled downtime in their aircraft during World War II (hence this is sometimes known as the Waddington Effect). The preventive maintenance increased the breakdowns rather than reducing them, with the chances for a downtime being highest shortly after the maintenance.

Subsequent studies by Ignizio supported this and also found that planned maintenance can increase downtime significantly. He also found that maintenance intervals may be too frequent, and 30% of the preventive maintenance was too frequent, increasing cost. Between 30% to 40% of preventive maintenance effort was spent on machines that had few failures to begin with, hence there was no benefit from the maintenance effort. Only 13% of the maintenance efforts actually created value for the company, whereas 19% were a waste of resources. Overall, it is difficult to determine where to do preventive maintenance, how to do it (a lot of the negative effects were from sloppy standards and time pressure on the maintenance personnel), how often to do it, and so on. Yet, not doing it may be worse. This post concludes a lengthy eleven-post series on maintenance. Now, go out, do maintenance, but not too much, but not too little either, and organize your industry!

Source

- Ignizio, James P. Optimizing Factory Performance: Cost-Effective Ways to Achieve Significant and Sustainable Improvement. 1st ed. New York: Mcgraw-Hill Professional, 2009. ISBN 0-07-163285-9.

- C. H. Waddington OR in World War 2: Operational Research Against the U-Boat, 1946.

I’ve experienced various ‘philosophies’, and all regard themselves as overarching. Masaaki Imai talked of the ‘kaizen umbrella’ under which came TQC, TQM, JIT etc.

I’m not comfortable with dropping 5S – or preferably 5C from the foundations. I always found #3 Clean & Check to be a real eye-opener, and as well as establishing a starting point, a basis for routine cleaning (which is basic maintenance, even if a bit janitorial) – and condition monitoring, itself the basis for establishing routines hopefully reflecting actual needs …thus avoiding excess PPMs. It’s also the basis for developing the capabilities of operational staff through undertaking routine maintenance tasks such as lubricating, tightening, changing filters etc. …leaving the time-served technicians to undertake tasks more appropriate to their capabilities.

Hi Steve, I like the description of “umbrella” philosophies, where whatever method it is tries to be in charge of everything else. For me as a lean guy, the top umbrella is obviously lean 🙂

Completely agree with you view on the TPM house and the comparison between TPM, TQM & Lean. The saying goes “If you only have a hammer you’ll see every thing as a nail to be hit”. Similarly we have to use the right tool for right purposes.

On the Waddignton effect on Preventive maintenance, I belive this is why we have to move away from time based maintenance to condition based maintenance that’s triggered by sensors and even IoT.

But I belive another area always not focused is quality or reliability. Most of the TPM efforts seems to focus on improving availability rather than focusing on reliability, which some causes is a hidden factory.

I agree with Steve Milner on 5S. It would make sense to include it within Autonomous Maintenance Pillar rather to drop it completely. Especially the first 2S i.e cleaning and arranging fit well with operators routine daily maintenance activities.

It’s is such a pity that 5S is not wel understood. I learned in this topic that all of you really don’t grasp the real purpose of 5S. This valuable program is the first loss analysis when starting such a big change program as TPM. It create more ownership for future losses. It learns that people see more losses -and/or create a platform that with losses they suffer for many years are elminated., people feel listened to. 5S is all about change and has nothing to do with only cleaning etc. . It makes sure that the team dynamics are becoming visable , Its makes sure that people leran to work with KPI’and KAI’s etc. It makes sure that teams agree upon deviding ownership of area’s that use to be nobody’s care. I can go on and on, That is why 5S is in the foundation.