The next pillar in this series on Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) is planned maintenance. The idea is instead of fixing issues after the machine breaks, you do maintenance so it doesn’t break in the first place. Like autonomous maintenance, this is one of the pillars where TPM really shines and adds value to manufacturing. Let’s have a deeper look into planned maintenance.

The next pillar in this series on Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) is planned maintenance. The idea is instead of fixing issues after the machine breaks, you do maintenance so it doesn’t break in the first place. Like autonomous maintenance, this is one of the pillars where TPM really shines and adds value to manufacturing. Let’s have a deeper look into planned maintenance.

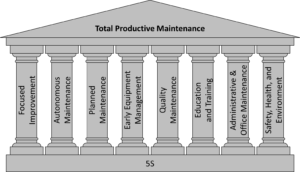

For a quick reference, here again are the eight pillars of TPM. The bold one is the focus of this blog post.

- Focused Improvement (meaning Continuous Improvement)

- Autonomous Maintenance

- Planned Maintenance

- Early Equipment Management (meaning Design for Maintenance)

- Quality Maintenance (which in lean would be called Jidoka)

- Education and Training (which in lean would be part of standardization)

- Administrative & Office Maintenance

- Safety, Health, and Environment

Overview of Planned Maintenance

Another very useful tool is planned maintenance. In Japanese this would be Keikaku Hozen (計画 保全 for plan; project; schedule; scheme; program; and preservation; integrity; conservation; maintenance). Sometimes it is also called preventive maintenance or, if it includes lots of data gathering, predictive maintenance.

Another very useful tool is planned maintenance. In Japanese this would be Keikaku Hozen (計画 保全 for plan; project; schedule; scheme; program; and preservation; integrity; conservation; maintenance). Sometimes it is also called preventive maintenance or, if it includes lots of data gathering, predictive maintenance.

The basic idea here is to do preventive maintenance (i.e., fix it before it breaks). In most cases this will be a regular scheduled maintenance, although there may also be unplanned preventive maintenance (i.e., unplanned planned maintenance?) if there is information on an upcoming problem. Hence it may have been better to name this pillar “preventive maintenance” rather than “planned maintenance.”

Let’s take an example of your car. You have scheduled maintenance (i.e., your regular oil change). The advantage of the scheduled maintenance is that you can schedule it for a time when you don’t need your car. You do it before or after (instead of while) you have to drive across the continent.

Let’s take an example of your car. You have scheduled maintenance (i.e., your regular oil change). The advantage of the scheduled maintenance is that you can schedule it for a time when you don’t need your car. You do it before or after (instead of while) you have to drive across the continent.

Unplanned maintenance in your car would be a yellow warning light . This indicates that something is amiss and should be checked eventually. (Don’t mix this up with red warning lights, which usually indicate serious problems and the car should be stopped as soon as safely possible. Consult your manual for proper procedures). Yet, you still may be able to schedule the maintenance to a time of your convenience, rather than RIGHT NOW.

Unplanned maintenance in your car would be a yellow warning light . This indicates that something is amiss and should be checked eventually. (Don’t mix this up with red warning lights, which usually indicate serious problems and the car should be stopped as soon as safely possible. Consult your manual for proper procedures). Yet, you still may be able to schedule the maintenance to a time of your convenience, rather than RIGHT NOW.

The same applies to machines on your shop floor. With planned maintenance, you can schedule the downtime for maintenance (both scheduled and unscheduled preventive maintenance) to a time of your choosing. If it is an annual maintenance event, you of course pick the off-season. If it is a shorter period (weekly or monthly), you may pick an off-shift or a weekend.

In any case, you can plan the production capacity much better. Not only that, but you can also plan the maintenance capacity much better. You distribute your scheduled maintenance over time, so your maintenance personnel is neither overloaded nor underworked, while still having capacity for emergency repairs. You can even postpone a scheduled maintenance somewhat if your maintenance people are busy dealing with breakdowns.

Benefit of Planned Maintenance

Planned maintenance is usually the cheaper option over random unplanned breakdowns. A breakdown usually comes when you need the machine the most. Your car may break down when you just left with your family for a three-week road-trip vacation, or when you are on your way to a job interview for your dream job. These are really bad times for a car to break down. Rather than you planning the maintenance, the maintenance plans you. In a factory, it may also lead to workers idling, delayed deliveries, and other effects from the delay. The repair may also be much more expensive. If you neglect to change your oil in your car, sooner or later your engine is going to die on you. You could have had a lot of oil changes for the price of a new engine.

Planned maintenance is usually the cheaper option over random unplanned breakdowns. A breakdown usually comes when you need the machine the most. Your car may break down when you just left with your family for a three-week road-trip vacation, or when you are on your way to a job interview for your dream job. These are really bad times for a car to break down. Rather than you planning the maintenance, the maintenance plans you. In a factory, it may also lead to workers idling, delayed deliveries, and other effects from the delay. The repair may also be much more expensive. If you neglect to change your oil in your car, sooner or later your engine is going to die on you. You could have had a lot of oil changes for the price of a new engine.

How Much Planned Maintenance

The question is now what type of maintenance you should plan when. This is difficult to answer. Since breakdowns are (hopefully) rare occurrences, it is difficult to get good data on the types and frequencies of breakdowns. It is also a lot of work to collect the data. For example, the airline industry has usually good data on their planes, since there are a) a lot of them and b) people really don’t want planes to crash. Hence, a lot of effort is put into understanding and maintaining aircraft.

It may be different in your company. The machines you are using were probably produced in much smaller quantities than aircraft, or your machine may even be unique. Still, even then you may get your hands on data for the components. Manufacturers often have information on the life cycle of ball bearings or valves. You may also start to collect data yourself. This can be, for example, statistics on previous breakdowns. One plant I worked in had a testing machine that pressure tested some pipes. They noticed that the O-ring sealing the connection between the machine and the part wore out every 15 000 parts, leading to false positives (i.e., defects that were not really defects). The solution was to change the O-ring every 12 000 parts to be on the safe side.

It may be different in your company. The machines you are using were probably produced in much smaller quantities than aircraft, or your machine may even be unique. Still, even then you may get your hands on data for the components. Manufacturers often have information on the life cycle of ball bearings or valves. You may also start to collect data yourself. This can be, for example, statistics on previous breakdowns. One plant I worked in had a testing machine that pressure tested some pipes. They noticed that the O-ring sealing the connection between the machine and the part wore out every 15 000 parts, leading to false positives (i.e., defects that were not really defects). The solution was to change the O-ring every 12 000 parts to be on the safe side.

You may also observe machine performance. Statistical process control is a tool from quality management, but it can easily be adapted to monitor the performance of your machine. If you see any worrying trends, counteract before the machine breaks.

You may also observe machine performance. Statistical process control is a tool from quality management, but it can easily be adapted to monitor the performance of your machine. If you see any worrying trends, counteract before the machine breaks.

Collecting this data is an effort and an expense. The more data you collect, the more effectively you can plan your maintenance, the better it is to find a trade off between too much and too little maintenance. But this is hard and there are no easy solutions. In many cases, especially in smaller companies, this comes down to gut feeling, which may or may not be accurate. Another problem is that if you do lots of planned maintenance, your machines will rarely break, so it looks like the maintenance may not have been necessary in the first place. Then there are also different stakeholders. The maintenance department may get yelled at if something breaks, hence they tend toward more maintenance (and hence to more maintenance people and hence more power for the head of maintenance). Maintenance consultants may also err on the side of too much maintenance, since it is what they are paid for. Plant managers, on the other hand, may or may not err toward too little maintenance, especially since there is a time lag between reducing maintenance expenses and the machine blowing up. By the time machine performance suffers from too little maintenance, the manager may already be on another position.

Again, a very valid and useful tool for industry! Now, go out, maintain your machines so they don’t break (or at least break less), and organize your industry!

P.S.: Many thanks to Leandro Barreda and Gil Santos for nudging me to write about maintenance.

Series Overview

- A Brief History of Maintenance

- What Are the Goals of Maintenance?

- An Overview of the Eight Pillars of Total Productive Maintenance

- The Pillars of TPM – Focused Improvement

- The Pillars of TPM – Autonomous Maintenance

- The Pillars of TPM – Planned Maintenance

- The Pillars of TPM – Early Equipment Management

- The Pillars of TPM – Quality, Training, Administration, and Safety

- The Pillars of TPM – The Missing Pillar Reactive Maintenance?