In this and subsequent posts I will have a deeper look at the different pillars of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM). This first post looks at the pillar of focused improvement, which is practically identical with continuous improvement. However, it can be argued if this should be its own pillar or if it should be part of the foundation of a house. I will tell you which parts I like and which ones I don’t, based on my knowledge in lean. Hopefully this helps you to figure out which parts to use, which ones to not use, and which ones to modify to fit your shop floor. But feel free to disagree. I am looking forward to your comments, as I will surely learn something form them. Anyway, let’s have a look at this pillar through my “lean glasses.”

In this and subsequent posts I will have a deeper look at the different pillars of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM). This first post looks at the pillar of focused improvement, which is practically identical with continuous improvement. However, it can be argued if this should be its own pillar or if it should be part of the foundation of a house. I will tell you which parts I like and which ones I don’t, based on my knowledge in lean. Hopefully this helps you to figure out which parts to use, which ones to not use, and which ones to modify to fit your shop floor. But feel free to disagree. I am looking forward to your comments, as I will surely learn something form them. Anyway, let’s have a look at this pillar through my “lean glasses.”

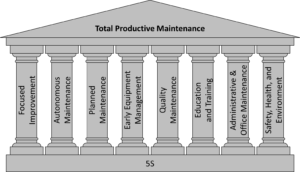

For a quick reference, here again are the eight pillars of TPM. The bold one is the focus of this blog post.

- Focused Improvement (meaning continuous improvement)

- Autonomous Maintenance

- Planned Maintenance

- Early Equipment Management (meaning Design for Maintenance)

- Quality Maintenance (which in lean would be called Jidoka)

- Education and Training (which in lean would be part of standardization)

- Administrative & Office Maintenance

- Safety, Health, and Environment

Overview of Focused Improvement

The first pillar I would like to discuss is focused improvement. In lean, this would be continuous improvement (i.e. kaizen), and much TPM literature also simply uses the Japanese term kaizen. In Japanese it is even called Kobetsu-Kaizen (個別 改善 for individual; separate; personal; case-by-case and betterment; improvement). Kaizen is obviously also one of the core philosophies in lean.

The first pillar I would like to discuss is focused improvement. In lean, this would be continuous improvement (i.e. kaizen), and much TPM literature also simply uses the Japanese term kaizen. In Japanese it is even called Kobetsu-Kaizen (個別 改善 for individual; separate; personal; case-by-case and betterment; improvement). Kaizen is obviously also one of the core philosophies in lean.

The key to continuous improvement is to first pick the right problems, and then to make sure that they are actually solved. Both parts are not that easy. To pick the right problem, hoshin kanri can help to pick larger projects. Especially for smaller projects, an estimation of the cost and benefit may be helpful.

For the actual implementation, PDCA is the right tool. As always, make sure not to forget the “check” and “act” part to verify if the “improvement” has actually improved something.

For the actual implementation, PDCA is the right tool. As always, make sure not to forget the “check” and “act” part to verify if the “improvement” has actually improved something.

In TPM, however, many descriptions of “focused improvement” seem to fall a bit short of the idea of kaizen in lean. Naturally, since the topic is maintenance, it is more focused on improving maintenance, both regarding how to do it and how to improve the performance. This is fine. The bigger problem is that TPM often focuses solely on eliminating waste, although this misconception also happens in lean frequently enough too.

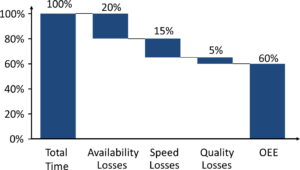

In particular, TPM focuses on eliminating losses in machine performance. Like lean, TPM calculates an Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE). This is the same as in lean, although TPM often uses a slightly different and in my view inferior formula to calculate OEE. But as in lean, they group the losses by availability, speed, and quality losses. However, the final number is the same, and the OEE is a good tool if you want to understand and reduce machine downtime.

The Types of Waste in TPM–Focused Improvement

TPM also looks at other types of waste. In lean you may be familiar with the classical seven types of waste as shown below. TPM has expanded this to many more, and uses sixteen types of waste. These are sometimes but inconsistently grouped by availability, speed, and quality losses from the OEE.

Here is one possible list of these sixteen losses. I found quite a few but different lists, but I won’t go into details here. Often it is also arranged into the classical OEE subgroups of availability losses, performance losses (or speed losses), and quality losses.

- Planned Machine Stop

- Unplanned Machine Stop (Breakdown)

- Setup and Adjustment Losses

- Ramp-Up Losses

- Minor Stops

- Speed Losses

- Defect and Rework Losses

- Shutdown Losses

- Management Losses

- Motion

- Line Organization

- Logistics

- Adjustments

- Loss of Energy

- Die Jig and Tool Losses

- Yield Losses

For me, this is not a good list (but then I may be biased by being used to the seven types of waste in lean). I have three gripes about this list, and then some more about the pillar itself. First, it seems to be overlapping. For example, a lot of the entries, like set-ups or shutdown losses, could be considered planned stops. Another example for a possible overlap are the ramp-up losses, the set-up and adjustment losses, and the adjustment losses. There may be small differences, but for me these are the same.

Second, I have the gut feeling that this list is incomplete. For example, where would you put a machine that is waiting on another machine? Is that line organization? Or is it logistics? What if it is not a line? If you have loss of energy, why don’t you have loss of wasted material? Using consulting speak, the list is not MECE: it is not mutually exclusive and completely exhaustive. In my experience, the longer a list is, the more difficult it is to make it MECE. However, it is fine if this list of losses is not intended to be MECE but only serves as inspiration.

Second, I have the gut feeling that this list is incomplete. For example, where would you put a machine that is waiting on another machine? Is that line organization? Or is it logistics? What if it is not a line? If you have loss of energy, why don’t you have loss of wasted material? Using consulting speak, the list is not MECE: it is not mutually exclusive and completely exhaustive. In my experience, the longer a list is, the more difficult it is to make it MECE. However, it is fine if this list of losses is not intended to be MECE but only serves as inspiration.

Finally, I find it difficult to measure these losses. In general it is important to measure your key performance indicators (KPI). How do you measure management losses? How do you measure line organization? It is difficult to improve what you can’t measure.

Is This a Good Pillar?

But there is a bigger oversight besides the list with sixteen types of waste (muda). Reducing waste is important, but it is only one of three evils in manufacturing, and waste is the least important one in lean. The other two are unevenness (mura) and overburden (muri), where overburden is the most important type of waste. This is also relevant for maintenance, but TPM often neglects unevenness and overburden. But again, this unfortunately also happens in lean often enough. If you run your machine too fast or too hard (overburden), breakdowns become more likely. The same goes for the workers. If your system fluctuates (unevenness), it can also lead to maintenance problems. I admit overlooking, or at least neglecting, unevenness and overburden is common in lean, but I find these important aspects for improvement.

Finally, I believe continuous improvement is very important. However, I find it odd to make it a separate pillar. If I have a pillar for continuous improvement, does this mean that planned maintenance does not include continuous improvement? Surely not, and surely not what the creators of this house of TPM intended. If we stay with the analogy of the house, continuous improvement should be not a separate pillar, but part of the foundation, influencing all pillars that rest on it.

But again, I am a lean guy, and the TPM framework is not my natural environment. Maybe it makes more sense for people that are trained in TPM. And again, the idea of continuous improvement is very relevant! The goal of this series of blog posts is to give you ideas and suggestions on what parts of the TPM framework are useful for you, which ones are not, and how you could modify it to get the most out of it for your shop floor. In my next post I will continue with the next pillars. Now, go out, improve your maintenance, and organize your industry!

P.S.: Many thanks to Leandro Barreda and Gil Santos for nudging me to write about maintenance.

Series Overview

- A Brief History of Maintenance

- What Are the Goals of Maintenance?

- An Overview of the Eight Pillars of Total Productive Maintenance

- The Pillars of TPM – Focused Improvement

- The Pillars of TPM – Autonomous Maintenance

- The Pillars of TPM – Planned Maintenance

- The Pillars of TPM – Early Equipment Management

- The Pillars of TPM – Quality, Training, Administration, and Safety

- The Pillars of TPM – The Missing Pillar Reactive Maintenance?

Interesting that you refer to ‘speed losses’. So often the word ‘performance’ is used – which is so vague as to be meaningless. I’ve always preferred the word ‘utilisation’. This would then cover a speed loss – so if a -say- packing machine is supposed to be running at 200 packs / min and its only running at 180, the loss is clear. If its running at 200 but only 180 charging slots are filled, or if its running at 200 but ‘fillers’ (people or machines) are not working at all then its clearly being under-utilised, although its capable of running at the right speed.

Context is also important. At an extreme, a combine harvester might be under-utilised for 11 months of the year ….but it doesn’t matter, as long as its capable of 24/7 running at harvest time!

Hi Steve, unfortunately definitions often vary. If I hear utilization, I would think about the machine running, but regardless of the speed and quality. If you include speed and quality, I would call this OEE. But unfortunately, this is not standardized.

In aviation, it is common to receive improvement reports. Problems solved by maintenance and sent to the aircraft manufacturer in order to be applied to the rest of the aircraft belonging to other customers. Something like a “recall” but carried out by the maintenance team itself.

Hi Christoph,

I totally agree with your point here. I always interpret these pillars as having overlapping starting points rather than trained work through a structure that has no agreed upon order. To that point, I believe it was Seiichi Nakajima who devised a 12 step process. The pillars being the ingredients, the 12 steps being the method or instruction. The entirety of TPM tends to be more readily adopted by Japanese companies than by European and American companies. In some part due to competition from RCM (Reliability Centred Maintenance). Which I would argue tends to similarly get more lip service than it does real engagement.

My rationale for a business adopting RCM over TPM is that many of the ‘pillars’ and a good part of the 12-step process is already in place. The US aircraft industry which spawned RCM and US military which quickly adopted it had for a longer period of time established, standard work, design for maintenance (Design for ‘X’) through Mil-Hdbk-472 and later Mil-Hdbk 407A, effective training training and importantly service organisation delivery and ‘organisation’ wide engagement.

Having an easily maintainable design and well trained maintenance technicians is nothing without the ability to deliver the correct parts, the right documents, as well as in date consumables to the right place and the right time, at the right price is a significant part of the availability equation.

Hi Jonathan, I have to admit I have not yet looked deeper at RCM (Reliability Centred Maintenance). But I do have some critical views of TPM, too, besides the good parts. More to come soon 🙂

Hi Christoph,

I really enjoyed when you talked about the first pillar and how you tied focused improvement into continuous improvement in the Kaizen principles. As a student learning about lean principles and Kaizen is the most impactful to me because it is a stressful thing for me to think about getting a job after finishing school and making changes to any kind of business, but thinking of it as just looking for little things that you observe and over time that makes a huge difference.