A minimum level in a supermarket gives you a warning that a stock out is imminent. Hopefully it also gives you enough time to prevent such a stock out, even though this may result in firefighting. In my last post I talked on how to use a minimum level. This post will look at how to determine a good minimum level.

What Influences the Minimum for My Supermarket?

Similar to the minimum of the fuel gauge, a minimum in a supermarket should give you enough time to react. At the same time, it should not annoy you with too many unnecessary warnings. To determine the minimum, you have to consider what kind of escalations you are willing to do to prevent an imminent stock out. It is almost always possible to move the kanban for the critical parts ahead in the queue for production, or more generally ahead in the information flow. Another option is shifting material in production around to accelerate the critical parts. However, shifting material around may be too much hassle and may cause even more chaos.

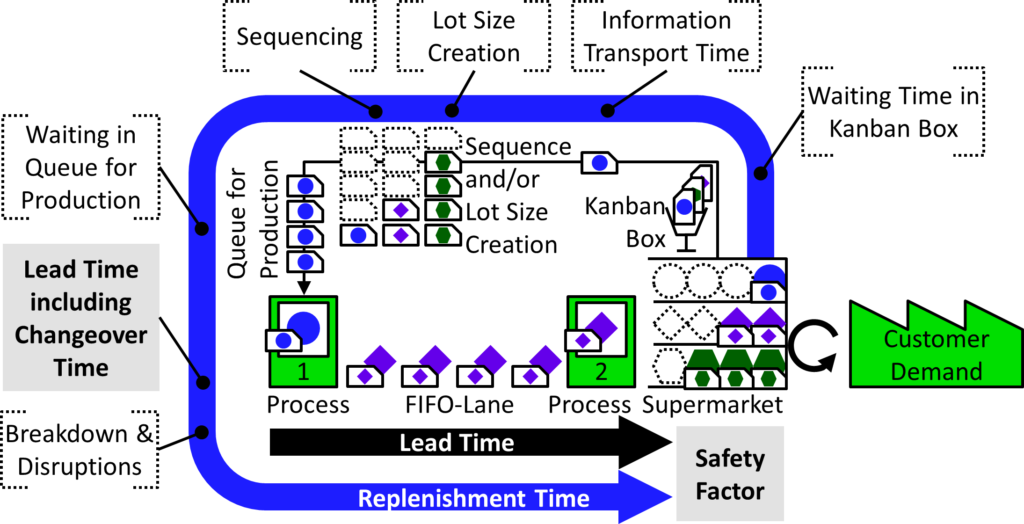

Depending on your action plan, the minimum could be different. The diagram below shows common elements contributing to the replenishment time. If you reach the minimum, there should be lots of kanban in the loop. If many of them are waiting, then you can fast-track the waiting times and get the needed parts to the front of the line in the queue for production.

How to Get a Good Minimum

Hence, the minimum level usually does not depend on the information flow in the replenishment time. It usually depends on the lead time, in combination with the emergency measures you are willing to take to prevent a stock out. What customer demand for this part type do you want to cover during the lead time, and how much can you shorten the lead time? It is almost always possible to accelerate the information flow. If you do not plan to re-sequence material during production your minimum inventory should cover the customer demand during the average lead time. This should include some safety for breakdowns, longer lead times, temporarily higher customer demand, or simply the time it takes to notice that you have reached the minimum and to take action. It should also include elements of the information flow that you cannot eliminate (e.g. a required lot size or a absolutely required production sequence).

If you plan to re-sequence the material during production, your minimum inventory could cover the customer demand during the minimum lead time, consisting of the processing times and transport times. This should also include some safety for breakdowns, delays, temporarily higher demand, or simply the time it takes to notice that you have reached the minimum and to take action.

Hence, it boils down on how much you think you can accelerate the replenishment time by skipping kanban and/or material queues. You need to cover the customer demand during this time to ensure a stable material availability. Keep in mind that in many cases you can find material in production already that will be finished.

When to Use a Minimum?

You should use a minimum level in the supermarket whenever it can help you prevent stock outs. I believe it is beneficial in many kanban systems, especially larger ones where the operators do not have a full picture of what is going on. If it is a small kanban loop where the operators have a good grasp of the situation, they may automatically react if they are running low. In a larger and difficult-to-understand pull systems, they may not. In any case, the minimum level is optional. It is quite possible to establish kanban systems without minimum levels. If you later find out that you need it, you may add the minimum later. A lot of kanban systems I have seen did not have a minimum, and those that had one did not always use it.

You should use a minimum level in the supermarket whenever it can help you prevent stock outs. I believe it is beneficial in many kanban systems, especially larger ones where the operators do not have a full picture of what is going on. If it is a small kanban loop where the operators have a good grasp of the situation, they may automatically react if they are running low. In a larger and difficult-to-understand pull systems, they may not. In any case, the minimum level is optional. It is quite possible to establish kanban systems without minimum levels. If you later find out that you need it, you may add the minimum later. A lot of kanban systems I have seen did not have a minimum, and those that had one did not always use it.

Implementing the minimum can be as simple as a colored area in the supermarket. If the inventory falls below this level, you have reached the minimum. It could also be a light signal or similar, or part of a digital system. The harder part is training the operators to understand the minimum and react if they reach the minimum.

Fine-Tuning the Minimum

Reaching the minimum causes firefighting to prevent a stock out. Hence, reaching the minimum should be an exception to avoid chaotic firefighting. Especially for a newly implemented minimum level, keep track of how often you reach it, and how often it actually resulted in escalations. If you reach the minimum too often, you may have too few kanban. A higher inventory limit (i.e., more kanban) would make it less likely to reach the minimum. If you never reach the minimum, you may have too many kanban … although this may be the lesser evil.

Reaching the minimum causes firefighting to prevent a stock out. Hence, reaching the minimum should be an exception to avoid chaotic firefighting. Especially for a newly implemented minimum level, keep track of how often you reach it, and how often it actually resulted in escalations. If you reach the minimum too often, you may have too few kanban. A higher inventory limit (i.e., more kanban) would make it less likely to reach the minimum. If you never reach the minimum, you may have too many kanban … although this may be the lesser evil.

You may find out that you still run out of stock frequently despite emergency escalations and while still having raw material available. If you lack raw materials, then it is a supplier issue. If it is an internal problem and you can’t react fast enough, then your minimum is too low. You do not have enough time to counteract the problem. In this case you may increase the minimum. Alternatively you may change the escalation procedure and maybe start re-sequencing work already in production. On the other hand, if your reaction leaves you with ample time frequently, then your minimum may be too large. Overall, like many lean methods the fine tuning is based on observing the system and adjusting as needed.

Altogether, a minimum level in a supermarket can help you to notice upcoming stock outs early enough to implement countermeasures. Usually this involves accelerating the information and material flow by prioritizing the parts that are about to run out. However, it won’t help you if you run out of everything. Getting a minimum warning too often will also increase chaos on the shop floor. Make sure to set the number of kanban and the minimum so that you reach the minimum only infrequently.

Now, go out, set a good minimum for your supermarket (if you think it will help), make sure that there is actually a response if the minimum is reached, and organize your industry!