Lean manufacturing often talks about true north. This is the direction in which your operations should move to become better. Sometimes that may be a bit fuzzy, so let’s have a look at what true north could include.

Lean manufacturing often talks about true north. This is the direction in which your operations should move to become better. Sometimes that may be a bit fuzzy, so let’s have a look at what true north could include.

I am fully aware that reaching true north in all aspects is unrealistic. If you actually reached true north, there would be nothing left to improve… which goes against my beliefs in manufacturing. You can always get better! Hence, achieving the list below is not realistic. But hey, as I am writing this, it is almost Christmas, and it is okay to make a wish! I hope that this unrealistic list helps you to get closer to true north in at least some aspects.

Introduction

In navigation, true north is the geographic north pole. It is at the axis around which the earth rotates (the other end would be the geographic south pole). Hence, if you want to go to the north pole, you just have to keep going north. The easiest way is using a compass with a magnetic needle. However, the needle does not point to the geographic north pole, but to the magnetic north pole (which, coincidentally, is a south pole in magnetic terms).

In navigation, true north is the geographic north pole. It is at the axis around which the earth rotates (the other end would be the geographic south pole). Hence, if you want to go to the north pole, you just have to keep going north. The easiest way is using a compass with a magnetic needle. However, the needle does not point to the geographic north pole, but to the magnetic north pole (which, coincidentally, is a south pole in magnetic terms).

Furthermore, the geographic north pole does not move much (only a bit due to earth-wobbling and plate tectonics). The magnetic north, however, moves quite a bit over time. Hence, your magnetic needle will point in the wrong direction, the closer you come to the pole. If you actually are at the north pole, the needle would point south, and you would be going the wrong direction. Good maps include information on this difference, and also on how it is expected to change over time. Lean (and others) use this true-north analogy to describe the direction your company should really be going. If you don’t know your true north, you may as well be going in circles.

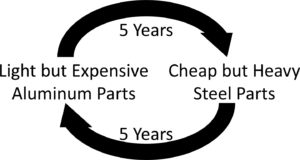

Let me give you an example from the automotive industry. There may be a push to reduce weight in cars for better performance. Hence, steel parts will be replaced with lighter but more expensive aluminum parts. Five years later, the drive is no longer weight, but cost. Aluminum parts will be replaced with cheaper but heavier steel parts. Another five years later, the drive is toward weight again, and the steel parts are replaced with the aluminum parts again. This cycle seems to repeat every five or so years. There is lots of movement, but it’s going in circles.

Let me give you an example from the automotive industry. There may be a push to reduce weight in cars for better performance. Hence, steel parts will be replaced with lighter but more expensive aluminum parts. Five years later, the drive is no longer weight, but cost. Aluminum parts will be replaced with cheaper but heavier steel parts. Another five years later, the drive is toward weight again, and the steel parts are replaced with the aluminum parts again. This cycle seems to repeat every five or so years. There is lots of movement, but it’s going in circles.

To me, a good company is a company that’s able to follow its true north even across multiple generations of leadership. Toyota, for example, pushed SMED for multiple decades to reduce the changeover time. So let’s look now at what true manufacturing in Lean could include.

Material Flow

The ideal material flow is in lot size one. This is also with a changeover duration of zero. In a world perfect for manufacturing, there would also be only one part type. However, this is not the goal for the entire company, and you probably would not want to drive toward a single-product company. However, the number of product variants should be a good trade-off between the effort of making multiple products and the benefit of making multiple products. In my experience, most companies have a lot of product variants in very small quantities whose continued existence should be seriously questioned. The production sequence of these different part types should be a perfect mix over the working duration. Distribute all part types as evenly across the day as you can.

The distance between the different processes should be zero, or as close to it as possible. Ideally, the machines are right next to each other. Do not ship parts around the world and back.

Inventory

Lean is legendary for reducing inventory. However, you can’t reduce the inventory to zero. You need parts that are worked on. You have parts in transit. But there should be no inventory except for the parts that are actually either moving or being processed. This requires Just-in-Time, Just-in-Sequence, and Ship-to-Line.

Lean is legendary for reducing inventory. However, you can’t reduce the inventory to zero. You need parts that are worked on. You have parts in transit. But there should be no inventory except for the parts that are actually either moving or being processed. This requires Just-in-Time, Just-in-Sequence, and Ship-to-Line.

Information Flow

The information flow should be instantaneous, and without any loss of information or miscommunication. All required information should be available. However, there should be no excess information, since it requires effort to gather and store, and it may hide the actually relevant information.

The information flow should be instantaneous, and without any loss of information or miscommunication. All required information should be available. However, there should be no excess information, since it requires effort to gather and store, and it may hide the actually relevant information.

Fluctuations

Simply said, there should be no fluctuations (mura) whatsoever. The customer orders regular like a Swiss clockwork, and suppliers and production deliver parts and products with equal regularity. Nothing of source-make-deliver should fluctuate. The production should be a flow shop, and the line should be perfectly balanced without any waiting time.

Simply said, there should be no fluctuations (mura) whatsoever. The customer orders regular like a Swiss clockwork, and suppliers and production deliver parts and products with equal regularity. Nothing of source-make-deliver should fluctuate. The production should be a flow shop, and the line should be perfectly balanced without any waiting time.

Quality

The perfect requirement for quality is simple: Zero defects and zero rework! Nothing should ever be defective or reworked. If there is a defect (which of course never happens), the processes should detect the defect automatically and the process should be stopped. This is the idea of Jidoka, or autonomation.

The perfect requirement for quality is simple: Zero defects and zero rework! Nothing should ever be defective or reworked. If there is a defect (which of course never happens), the processes should detect the defect automatically and the process should be stopped. This is the idea of Jidoka, or autonomation.

Waste

There should be no waste (muda). You surely know the seven types of waste. These should be eliminated.

Overburden

There should also be no overburden of the workers (muri). First and foremost, this requires a perfect safety record. It would also require the work being neither too difficult nor too easy, but just right without being monotonous. All employees and other people should be treated with respect. The workers should have a positive attitude toward work and the company.

There should also be no overburden of the workers (muri). First and foremost, this requires a perfect safety record. It would also require the work being neither too difficult nor too easy, but just right without being monotonous. All employees and other people should be treated with respect. The workers should have a positive attitude toward work and the company.

Continuous Improvement

If you have achieved true north, then there would be nothing left to improve. Nevertheless, on the way to true north, continuous improvement is an important part. Hence, you should have continuous improvement, or kaizen. This is not assigned to a continuous improvement specialist, but is engrained with all employees (including the CEO) and supported by management. Improvement follows the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) sequence.

If you have achieved true north, then there would be nothing left to improve. Nevertheless, on the way to true north, continuous improvement is an important part. Hence, you should have continuous improvement, or kaizen. This is not assigned to a continuous improvement specialist, but is engrained with all employees (including the CEO) and supported by management. Improvement follows the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) sequence.

Where Paradise Meets Reality

True north is not realistic. True North is a dream… but you never should stop dreaming! The idea is not necessarily to reach true north (do you actually want to go to the north pole every time you pick up a map?). But it should help you to find the right path.

You will also find that there are contradictions in the above list. For example, there should be no fluctuations, but work should also be not monotonous. Or, the effort of achieving zero defects may not be worth the cost. The closer you get to these different true norths, the more contradictions you will find. Luckily, most companies, possibly even including yours, still have a looong way to go before they even get close to true north.

Furthermore, you won’t be able to push everything toward true north at the same time. And that is where this laundry list of industrial paradise above may be helpful. Pick your focus areas! Which areas from the long list above are most relevant to your company? Where are you, and where do you want to be? If safety or generally overburden of the workers is unsatisfactory, it should be high up on your list, as should be quality. Continuous improvement is the actual process that helps you to go toward true north, wherever it may be for you. Overall, you have to decide which direction is most relevant for your company in the long term. It may not even be on this list, since I make no claim for completion. But you should know where you want to go. Otherwise you will be just wandering around aimlessly. Now, go out, pick your direction, and organize your industry!

Very good. Your texts are excellent. Congratulatios!

Very good, thanks for sharing Sir

Hi Christopher,

This may not mean much to you given you’re not from the US, but once upon a time in the sport of US football, there was a team that captured the hearts and minds of the nation’s sports fans (along with many others). The name of that team was the Green Bay Packers. As the team’s history history reveals…

The Green Bay Packers are the most successful franchise in professional football history. The team was founded in 1919, joined the NFL in 1920 and has won 13 titles in its 93 years of existence. Other teams may have won more Super Bowls, but none have more championships.

One of the most notable figures (for both leadership and inspiration both on and off the field) in the team’s history was Vince Lombardi…

As head coach and general manager of the Green Bay Packers, Vince Lombardi led the team to three NFL championships and to victories in Super Bowls I and II (1967 and 1968). Because of his success, he became a national symbol of single-minded determination to win.

One of the sayings the he is renowned for is as follows…

“IF WE CHASE PERFECTION, WE WILL CATCH EXCELLENCE.”

[Actual unabridged quotation: “Gentlemen, we will chase perfection, and we will chase it relentlessly, knowing all the while we can never attain it. But along the way, we shall catch excellence.”]

And in the CONTEXT of TRUE LEAN THINKING AND BEHAVING, that’s the role of highly-compelling TRUE NORTH ORIENTATION. And like PERFECTION, it’s NEVER truly attainable; but, if one defines it in a way that is truly inspirational/motivational to all TEAM MEMBERS and pursues it accordingly (i.e., COLLECTIVELY), one will likely attain AND SUSTAIN a level of EXCELLENCE that is difficult (for any other entity) to mimic… ala Toyota.

Sorry… Christoph, not Christopher.

Hello Jay, well said. True north is true perfection, and – unlike the geographic north pole – you can never reach it.

Don’t mind about the “Christopher“. It happens all the time…

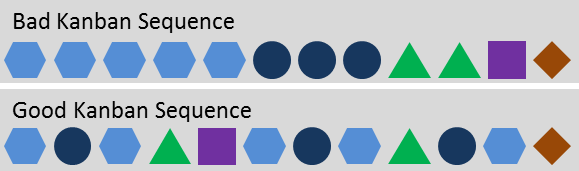

I don’t understand about your material flow kanban comparison. Why would you not want to group like with like? In the factory where I’m in charge of lean/continuous improvement*, our operators batch what’s similar so they can reduce the number of changeovers needed. Our schedule looks like your “Bad Kanban” graphic. Am I misunderstanding?

*I am not a specialist! I’m working with our managers and employees to coach them about principles and processes that will allow us to achieve greater stability and less waste. I provide the guidance and direction while supporting the workers and making sure their needs are met.

Great article! It’s nice to have dreams of manufacturing paradise!

@Renee, this is the idea of balancing/leveling/heijunka.

1) Making large lots reduce the c/o time, which saves time. This saved time can be measured easily by accounting

2) Making small lots increases the total C/O time, but requires less inventory and makes faster lead time. However, while the benefit is often larger than the additional time needed, many of these benefits are hard to quantify (see my post on the cost of inventory).

Overall, traditionally plants preferred large lots and less change over effort, but the insight from lean is that smaller lots are often better for the overall performance of the plant, even though it is hard to calculate this benefit.

Hi Christoph,

I like your posts! Delighting and well written as always you hit the very concept of lean in eliminating waste! There is this notion of having ‚to see‘ waste first before it can be eliminated.

If lean principles like OPF (one piece flow=zero waste) are not applied consistently resulting in an ideal state – the true north, the biggest portion of waste cannot be seen, and consequently not be eliminated.

Getting a true north, either as pure idealistic (zero waste with no system constraints considered) or a technically idealistic (considering system constraints like e.g. capacities) reveals all the waste compared to a current state. This is commonly part of the gap analysis.

At this point not having seen the whole waste (commonly known as gap analysis) we see improvements but NOT in pursue of true north. This constitutes a shortcut unfortunately taken quite frequently. This may be one of the reasons for lean projects not delivering substantial results.

It may sound strange but in Lean Thinking improvement is not enough – we might run in circles not holding towards true north!

Hi Christoph,

I enjoyed reading your post about “True North” in lean manufacturing. I found the symbolism to be quite spot on. I think that you comment about true north being perfection in lean manufacturing to be an interesting concept. When I think of lean I think of continuous improvement, and always trying to reach close to perfect. I also note your point about true north taking a long time for a company to achieve.

@Renee I also have wondered about the optimal Kanban order at first. Mixing the parts uniformly will lead to a balanced distribution at the outflow, optimally meeting the customer orders, which came in with the same distribution. Ideally, change over time is zero too. Of course neither is attainable in practice and reducing change overs might be the actual optimum – impossible to get to true north.

@Hemuth, yes, fluctuations (mura) often both generate and hide waste (muda). That is why Toyota considers fluctuations worse than waste. The worst is still overburden (muri)

Hi Nikolaus, actually, having a lot size of 1 is one of the true north goals that are actually achievable 🙂