This post looks at how to reduce fluctuations (mura) in manufacturing. It is a continuation of the previous post that looked at why fluctuations are so bad. Be warned, tackling fluctuations is often a tedious task that never ends, but it one of the important fundamentals for lean manufacturing. After all, the more stable a system runs, the more efficient it is. Leveling is one major method to reduce fluctuations that focuses on the production schedule. Line balancing is another one that focuses on the work content.

This post looks at how to reduce fluctuations (mura) in manufacturing. It is a continuation of the previous post that looked at why fluctuations are so bad. Be warned, tackling fluctuations is often a tedious task that never ends, but it one of the important fundamentals for lean manufacturing. After all, the more stable a system runs, the more efficient it is. Leveling is one major method to reduce fluctuations that focuses on the production schedule. Line balancing is another one that focuses on the work content.

How to Tackle Fluctuations

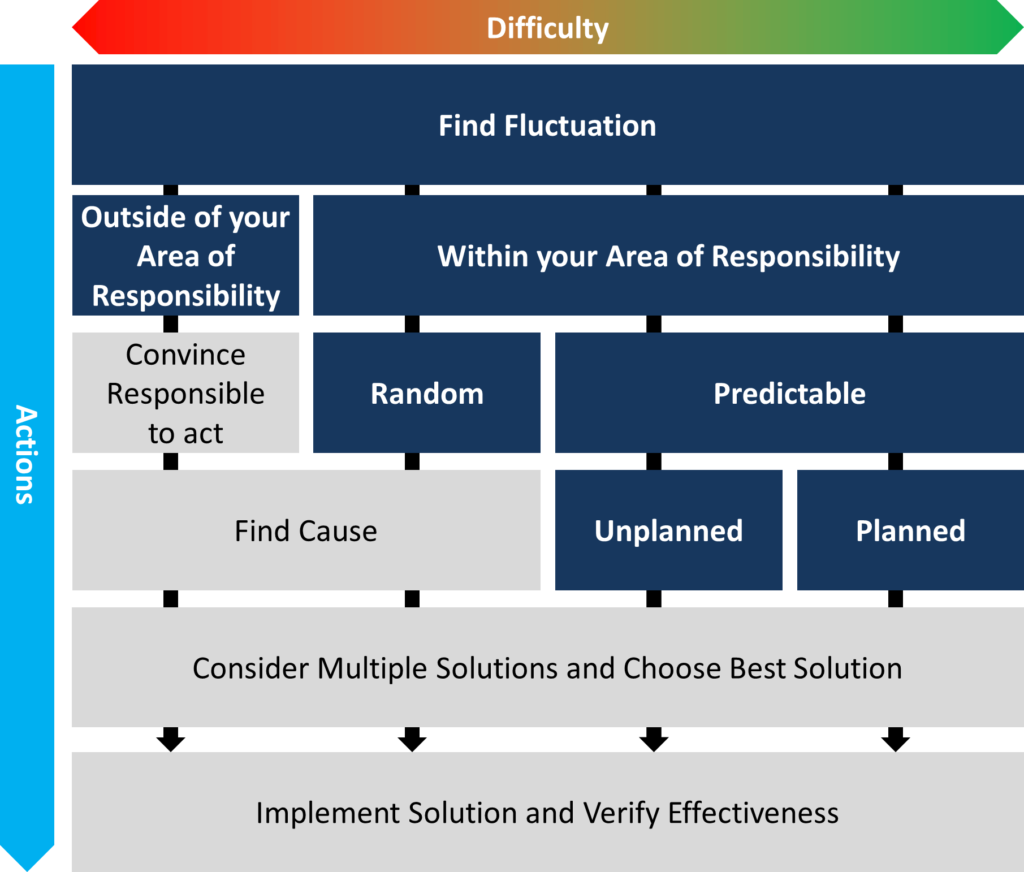

The process of reducing fluctuations follows a certain schema. I will go into more details of each of them later on. The illustration below also visualizes this approach. And again, it is tedious work!

- First, you would have to find the fluctuation to tackle.

- Next you have to check where it originates. If it originates outside of your area of responsibility, congratulations, you have found the probably most difficult problem. Not only do need to find the root cause, a solution, and implement the solution, but you also have to convince the person in charge to do so.

- If it is within your area of responsibility, it is a bit easier. You have to distinguish between random fluctuations like machine breakdowns, and predictable fluctuations like seasonality. If it is random, you have to find the root cause before developing and implementing a solution.

- If the fluctuation is predictable, then you have to distinguish between unplanned fluctuations like seasonality, or planned fluctuations like your production plan. The easiest case is probably a planned fluctuation, because (in theory) you could reduce it merely by changing your plan. In any case, you still need to develop a solution, implement it and check if it worked.

However, please note that due to the large number of possible reasons for fluctuations, this guide is only a rough outline. There are still plenty of things for you to analyze and decide on.

Select Fluctuation

The first question is which fluctuation you want to tackle. This is not an easy question. There will be lots of sources of fluctuations on your shop floor. It will feel like a ship in a stormy ocean, trying to decide which wave to investigate. It may be that you don’t even have much time to investigate a wave in more detail, since you are just trying to survive a wave. After this wave has passed, you are just trying to survive the next one, and so on. Switching this metaphor to the shop floor, you are constantly firefighting but not changing any of the fundamentals. You need to find time to reduce the size of the waves hitting you!

Maybe you are in the lucky situation that your waves are already much smaller. You are no longer in constant fear of drowning, but try to optimize yourself and make the waves even smaller. While this is probably much more profitable than a stormy ocean, it still leaves you with the problem which wave to tackle. And again, this is not an easy question. Toyota does quite a bit of monitoring to detect fluctuations, so it can act upon them.

Anyway, regardless if the waves are crashing over your head or just gently rocking your boat, you have to pick one to look at in more detail. Chances are that you have certain types of recurring problems. Those that give you the biggest headaches are potential candidates for improvement. Select a few of them for further consideration.

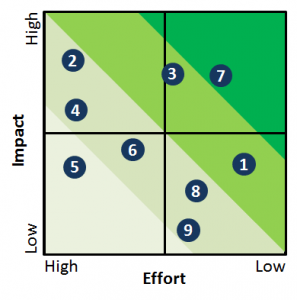

Like most improvement projects, the trade-off is between the impact and the effort of getting the impact. As explained in a previous post How to Manage Your Lean Projects – Prioritize, this is easiest done in an impact-effort matrix. Please note that both the impact and the effort are guesstimates. You probably don’t have any hard values, but take your (or your people’s) best guess.

Fluctuations Originate Outside Your Area of Responsibility?

Fluctuations can have a multitude of reasons. Your next steps depend on a couple of questions as described above. The first question you should ask is if the fluctuation originates within your area of responsibility, or not. If it is within your area, you have good control of the possible actions. It will be more difficult if it is from outside of your area. For example, if your supplier’s quality is rather unpredictable, then you have to work with your supplier to improve quality.

Fluctuations can have a multitude of reasons. Your next steps depend on a couple of questions as described above. The first question you should ask is if the fluctuation originates within your area of responsibility, or not. If it is within your area, you have good control of the possible actions. It will be more difficult if it is from outside of your area. For example, if your supplier’s quality is rather unpredictable, then you have to work with your supplier to improve quality.

The frequent problem with fluctuations originating from outside your area is the challenge to motivate others to work on the fluctuation. Hopefully, your supplier is actually willing to work on what is essentially your problem. Depending on your connection to the supplier and your influence on the supplier, the supplier may or may not be interested in the additional work to reduce fluctuations. In the worst case, you will get empty promises and no results. This can happen especially when you’re only a small customer for the supplier.

However, do consider that even though you think the fluctuations come from the supplier, they may actually originate with you! For example, if the deliveries of the supplier are somewhat chaotic around the desired delivery date, check if you don’t actually order just as chaotic on short notice from the supplier. There are probably other fluctuations that caused the fluctuations of the supplier, and it rarely originates only from one location.

Such situations can quickly turn into a blame game. You blame your supplier, your supplier blames you or someone else, who then again blames someone else. Soon, the week is over, everybody is frustrated, and nothing has improved. Don’t go down that road; nothing useful will come out of it.

It is much better to address fluctuations originating from your own area of responsibility. These you can actually improve yourself … although it may be more work than just blaming someone else.

Random or Predictable Fluctuation?

The next question you have to ask yourself is if the fluctuations are random or predictable. Predictable ones are easier to understand, because you probably already know why the fluctuation is happening. Seasonality is a common, predictable fluctuation. More difficult are random fluctuations. They happen with no warning. Common examples are machine breakdowns. Often with random fluctuations you first have to find out why the fluctuation is happening. This will feel like a detective work. You have to collect clues (data) to understand the situation and to catch the killer (the fluctuation).

Actually fixing it may often be quite simple. I had plenty of situations where a machine was behaving erratically and messing up the material flow just because a sensor came loose over time. Simply tightening the screws fixed the problem.

Planned or Unplanned Fluctuations?

The final question to ask is if your fluctuations are planned or unplanned. Many fluctuations are unplanned. Some are at least predictable like seasonality, but others are almost impossible to predict like machine breakdowns. However, some other fluctuations are actually planned! This sounds counterintuitive, because why would you plan fluctuations? However, by setting up a production plan, a work schedule, or an imbalanced line, you actually plan fluctuations! Planned fluctuations are hence often easier to understand, since they are … well … planned. To reduce them you just have to … well … plan better. Key examples here are leveling or line balancing. In my next post I will talk a bit more on the difficult topic of reducing fluctuations. Now, go out, tackle those waves, and organize your industry!

The final question to ask is if your fluctuations are planned or unplanned. Many fluctuations are unplanned. Some are at least predictable like seasonality, but others are almost impossible to predict like machine breakdowns. However, some other fluctuations are actually planned! This sounds counterintuitive, because why would you plan fluctuations? However, by setting up a production plan, a work schedule, or an imbalanced line, you actually plan fluctuations! Planned fluctuations are hence often easier to understand, since they are … well … planned. To reduce them you just have to … well … plan better. Key examples here are leveling or line balancing. In my next post I will talk a bit more on the difficult topic of reducing fluctuations. Now, go out, tackle those waves, and organize your industry!