You probably hate long drudging hours working in the office and feeling really worn out at the end of the day. Maybe you’re sitting in an office working right now (and of course your reading my blog means you are working 😉 ), knowing that you will be worn out at the end of the day. This post is especially for you, looking at work hours and productivity. The good news is: Less is more, but don’t overdo it!

You probably hate long drudging hours working in the office and feeling really worn out at the end of the day. Maybe you’re sitting in an office working right now (and of course your reading my blog means you are working 😉 ), knowing that you will be worn out at the end of the day. This post is especially for you, looking at work hours and productivity. The good news is: Less is more, but don’t overdo it!

Industrial Revolution

During the early years of the Industrial Revolution, the goal of the factory owner was to have his employees work as long as possible. Due to the lack of electric light, this usually meant from sunrise to sunset, sometimes even reaching sixteen hours during summer. The factory owners justified this by reasoning that if the worker was working, he had no time to get drunk and make other trouble – although I suspect that in the back of their minds was also the idea that longer work for the same wage meant more profit. With the onset of electric light around 1880, there were attempts for even longer working hours.

Unsurprisingly, workers did NOT like to work sixteen hours per day, and in 1830 unions in England discussed an eight-hour day … meaning they cut the maximum work time in half. But it was not quickly adopted, and only in 1847 did the Factory Act decree a ten-hour workday … but this was not really enforced. Only from 1867 onward was a ten-hour workday common, and only from 1900 onward was it a standard. The British Navy even switched to an eight-hour workday in 1891 for many of its employees.

Most people expected that a reduction in work hours increases productivity per hour, due to the workers being better rested. What they absolutely did NOT expect was that not only did the hourly productivity go up, the daily productivity went up too! Frequently workers were able to produce more in eight hours than they did in fourteen to sixteen hours before. Nowadays you would call this a win-win situation, where the factory owner got more stuff produced and the worker got more free time for leisure and other private activities. Their work-life balance increased significantly.

Frederick Taylor in the USA

Similarly, Frederick Winslow Taylor (the father of Scientific Management and inventor of HSS Steel) experimented with work hours in the USA. As a consultant he often advocated a reduction of work hours to improve productivity. In a plant where women were inspecting ball bearings he gradually reduced daily work time from 10.5 hours to 10 to 9.5 to 9 and finally to 8.5 hours. He found that the daily output increased by 33%, and quality got better too!

Five-Day Work Week

Throughout history, not only the daily work time but also the number of weekly workdays have been reduced. Around 1850, many people worked six or even seven days per week. Eventually companies and countries started reducing the work days. Ford reduced the work week to five days in 1926. The Fair Labor Act in the US (1938) reduced the work week to forty hours, resulting in a two-day weekend. In Germany, unions successfully promoted a forty-hour five-day work week. Their campaign had a poster with a young kid stating “On Saturday Daddy belongs to me!”

Throughout history, not only the daily work time but also the number of weekly workdays have been reduced. Around 1850, many people worked six or even seven days per week. Eventually companies and countries started reducing the work days. Ford reduced the work week to five days in 1926. The Fair Labor Act in the US (1938) reduced the work week to forty hours, resulting in a two-day weekend. In Germany, unions successfully promoted a forty-hour five-day work week. Their campaign had a poster with a young kid stating “On Saturday Daddy belongs to me!”

As a result, consumption increased. People had more time to spend money on stuff.

Microsoft Japan Four-Day Work Week

There are also modern-day examples. Just recently Microsoft Japan experimented with a four-day work week. Now, Japan has some very brutal working hours (see my post on The Dark Side of Japanese Working Society). In August 2019, Microsoft Japan tried out a radical four-day work week without reducing pay. They gave all employees special paid leave for Friday. Effectively, they reduced the work time by 20% (actually 25.4% since there were five Fridays in August).

There are also modern-day examples. Just recently Microsoft Japan experimented with a four-day work week. Now, Japan has some very brutal working hours (see my post on The Dark Side of Japanese Working Society). In August 2019, Microsoft Japan tried out a radical four-day work week without reducing pay. They gave all employees special paid leave for Friday. Effectively, they reduced the work time by 20% (actually 25.4% since there were five Fridays in August).

The result was again surprising. They determined an overall 40% productivity increase despite reducing work time by 25%! (Although it is not quite clear how “productivity” was measured.) On hard data they measured 58.7% fewer pages printed, and 23.1% less power consumption. Meetings also became much shorter. Unsurprisingly, 92% of the employees said that they liked the four-day work week, and truly enjoyed the extra day off. Unfortunately for the employees, Microsoft went back to a normal five-day work week at the end of the trial. It is to be seen (hoped) that they may repeat this trial or even implement it permanently.

Many other places experimented with a four-day workweek, as for example parts of Utah, Hawaii, Gambia, Romania, New Zealand, and the UK. Many employees enjoyed the extra day off, but others felt more pressure to complete the work in less time.

Statistical Data

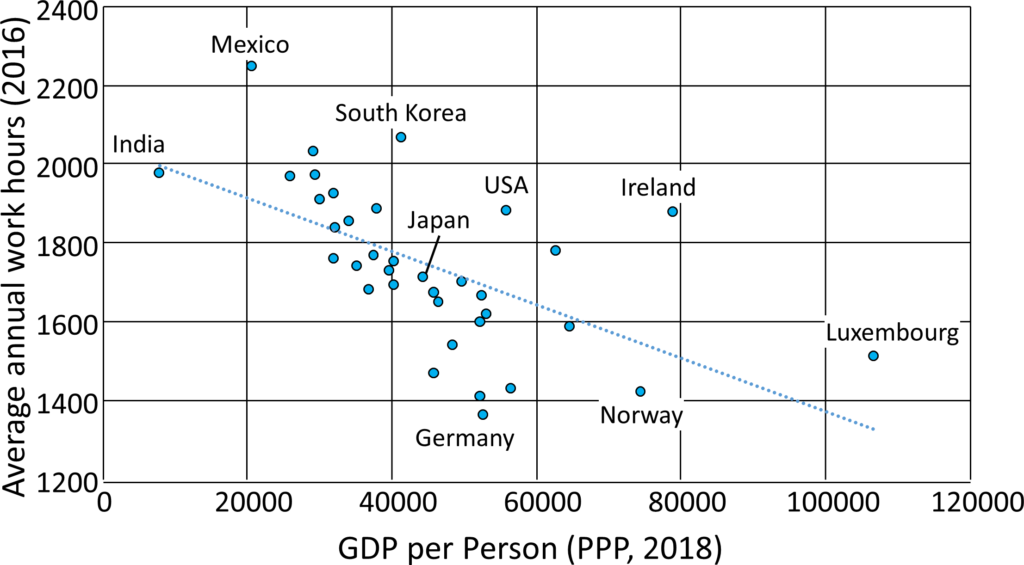

There seems also to be a statistical relation when comparing the work hours, GDP, and happiness of different countries. Below is a plot of the GDP per person (purchasing power parity) in 2018 (latest data) against the annual work hours (2016, latest data). There seems to be a clear trend that richer countries work less. The full data set is available here as an Excel file.

There seems also to be a statistical relation when comparing the work hours, GDP, and happiness of different countries. Below is a plot of the GDP per person (purchasing power parity) in 2018 (latest data) against the annual work hours (2016, latest data). There seems to be a clear trend that richer countries work less. The full data set is available here as an Excel file.

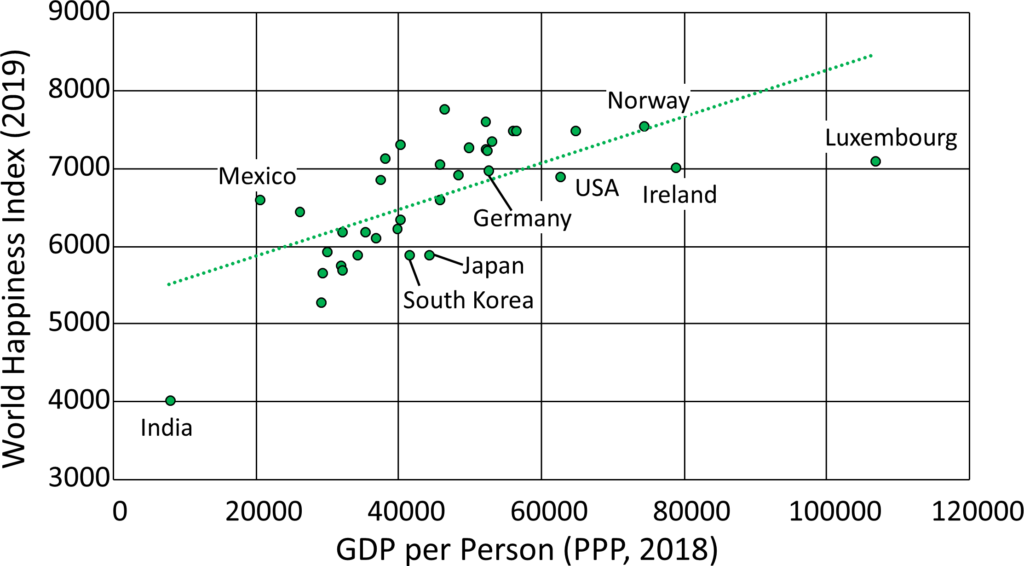

Similarly, plotting the happiness of these countries (as measured by the World Happiness Index) against GDP also shows a clear relation. There is also a strong relation between work hours and happiness.

Correlation Is Not Causation

Now, looking at this data, the extrapolation is clear: If nobody works, we would be the richest and happiest country in the world … although while I feel that while this linear extrapolation is attractive, it is probably not true. I doubt that we would be wealthy if nobody worked. Hence, the trend of reducing work hours while producing even more probably would not go on indefinitely. There are also examples where a reduction in work hours did not work out well, as for example the thirty-five-hour work week in France.

It may also apply only to a lesser degree for some situations. If you work at an assembly line that has a certain takt, then the output is indeed very closely correlated to the working time. Yet, measuring productivity in office jobs is tricky, and hard numbers are difficult to come by. I personally believe that a good mix of work and leisure is important, but I find it really hard to give concrete advice on working hours. It probably differs from industry to industry, from task to task, and even from person to person. But I am convinced that more working hours is not always better. In any case, despite the lack of solid advice, I hope this blog post was interesting to you. Now go out, take time to relax, and organize your industry!

P.S.: Many thanks to Rapinder Sawhney from the University of Tennessee for his great presentation at the ELEC 2019 in Milan that gave me the inspiration for this post!

Thanks for knowledge sharing Chris. Your post reminded me of a similar and also not intuitive question: taxation. Obviously, If you tax 0% then the Government has cero money but if the tax goes up to 100% is the same thing, no money for the Government. This is well illustrated by a Laffer Curve.

By the way, I’m writing from Mexico while sipping a latte at 10am on a Tuesday so I guess I’m a pretty happy outlier 😉

Hi Miguel, as a Professor I am also a very happy outlier 🙂

Not sure whether I should consider myself an outlier since I am in a taxi enroute to my hotel after flying from Italy to Germany. I’ve been following Allaboutlean blog for a while and I enjoyed the posts. Keep the posts coming please

All this could be interesting if true. The GDP and Hapiness and average working hours are so synthesized KPI that it is hard to believe the simple correlations are working.

And indeed if you take a look to the cirrelation index there is a quite poor one not strong: R2=35% only for GDP per person vs average annual work hours and R2=43% only for GDP per person vs hapiness. When R2 > 60% we can say that there could be a correlation.

In fact when you take out of data the extreme dots : India, Mexico, USA, Norway, Switzerland, Ireland (?) and Luxembourg we see a strong correlation between GDP and annual work hours – 79% and 68% with hapiness. That suggest that linearity stops when GDP is very low and very big – and it works in the middle. Withe hapiness the correlation is better polynomiale, but with annual work hours it is not true.

But it is needed to get more dots to analyze correlation forward

Thanks for the article

Virgil

I agree, Virgil. As i said “Correlation Is Not Causation”, this is not stong, solid science, but all a bit fuzzy. It definitely breaks down at the extremes. With a linear model working not at all would be wealthiest, but that is (unfortunately) not true. Thanks for the background analysis!

Thanks for sharing these great knowledge and I have a question what about split breaks time for blue colors from one hour one shot to four breaks each one 15 min or two each one 30 min these action increase in productivity or not especially for high effort jobs

Hi Ramy, the timing of breaks is another important topic. But keep in mind that two breaks of 15 minutes will loose more productivity than 1 break of 30 minutes due to ramp down/start up times for the operators. For desk jobs a single 1 minute phone call can loose 5 minutes of work time due to the mind switching from the original task to the phone and back.