In my last post I looked at the span of control. This is very related to the workload of the supervisor. Hence in this post I would like to discuss how to adjust the supervisor workload. Usually, this is to reduce the workload, as most shop-floor supervisors are in my opinion overworked and have no time left for improvement. In some cases, however, you may have a situation where you want to give the rare underworked supervisor more work. Most of the approaches presented will work in both directions. Let’s look at some ideas:

In my last post I looked at the span of control. This is very related to the workload of the supervisor. Hence in this post I would like to discuss how to adjust the supervisor workload. Usually, this is to reduce the workload, as most shop-floor supervisors are in my opinion overworked and have no time left for improvement. In some cases, however, you may have a situation where you want to give the rare underworked supervisor more work. Most of the approaches presented will work in both directions. Let’s look at some ideas:

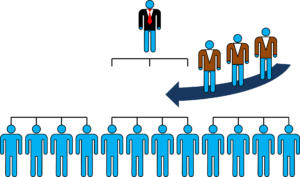

Split/Merge Groups

A common and easy solution to reduce the workload of supervisors is to make smaller groups. Toyota and Nissan use this approach on the shop floor, and their lowest-level-hierarchy span of control is much smaller than what Western industry uses. This seems to correlate with a much better performance in terms of speed, quality, and even cost on the shop floor (see my post The Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive for details).

A common and easy solution to reduce the workload of supervisors is to make smaller groups. Toyota and Nissan use this approach on the shop floor, and their lowest-level-hierarchy span of control is much smaller than what Western industry uses. This seems to correlate with a much better performance in terms of speed, quality, and even cost on the shop floor (see my post The Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive for details).

This could mean that you need more supervisors. In some cases this is the correct way to do it, and an additional person on the shop floor will reduce the work of the other supervisor(s).

Another option would be to promote a qualified worker to supervisor. On paper this will not increase the available manpower. While you have one supervisor more, you have one worker less. However, the work of managing other people does not go up linearly. Managing twenty people is MORE than double the work than managing ten people. Managers make do by cutting corners, and the quality of the management suffers. At Toyota, the lowest level (team leader) also helps out with regular work, and takes over the job of a worker if the worker is absent.

Another option would be to promote a qualified worker to supervisor. On paper this will not increase the available manpower. While you have one supervisor more, you have one worker less. However, the work of managing other people does not go up linearly. Managing twenty people is MORE than double the work than managing ten people. Managers make do by cutting corners, and the quality of the management suffers. At Toyota, the lowest level (team leader) also helps out with regular work, and takes over the job of a worker if the worker is absent.

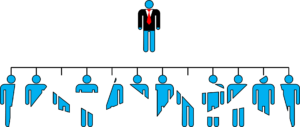

Add/Remove a Level of Hierarchy

If there is the need to split a lot of groups, it may be of interest to consider adding a level of hierarchy. This option is only for larger changes, as you need many more supervisors (to be hired or promoted). Not so good for small changes. It also comes with a lot of advantages and disadvantages, like giving people more chances for promotion but also making upper-level people more remote.

If there is the need to split a lot of groups, it may be of interest to consider adding a level of hierarchy. This option is only for larger changes, as you need many more supervisors (to be hired or promoted). Not so good for small changes. It also comes with a lot of advantages and disadvantages, like giving people more chances for promotion but also making upper-level people more remote.

Give an Assistant

Another idea is to give the supervisor an assistant, or maybe an assistant for a group of supervisors.

Another idea is to give the supervisor an assistant, or maybe an assistant for a group of supervisors.

On higher levels of hierarchy, this is very common. An assistant is often even seen as a status symbol, and on the highest levels people have multiple assistants for different tasks. In some cases such an assistant position may even be a fast-track for promotion.

On the lower levels of hierarchy, such assistants are rare. However, just because lower-level supervisors are paid (much, much) less, doesn’t mean that their workload is less. The work may have less decision making under uncertainty, and they usually leave at the end of the shift rather than amassing overtime, but they may also be overworked.

For example, when working closely with shop-floor supervisors, I notice that they do a LOT of data entry, and nobody on the higher levels cares much about that work as long as it is done. However, it is a lot of work, and I’m often wondering if it would be possible to centralize this data entry with an assistant. This assistant would specialize in data entry and could probably do the work faster than the different supervisors.

Add/Remove Other Tasks

Another option is to remove (or add) tasks from the workload of the supervisor. Are there certain repetitive tasks, possibly repetitive across multiple supervisors? Maybe you can get a person who specializes in this topic and subsequently can do the job better and faster than a supervisor?

Another option is to remove (or add) tasks from the workload of the supervisor. Are there certain repetitive tasks, possibly repetitive across multiple supervisors? Maybe you can get a person who specializes in this topic and subsequently can do the job better and faster than a supervisor?

Toyota, for example, has a mind-boggling number of people on the shop floor who solve problems. Western companies would be amazed to see how many people at Toyota exist solely to support the shop floor. In the Western world these people were often cut, with drastic results on quality and speed.

Optimize

Yet another way to reduce the workload of the supervisor is to optimize and improve his work. Can you reduce walking distances? Does he have the tools he needs, and are these tools working well? Quite a few tools from the lean toolbox could be applied here, from 5S to the spaghetti diagram.

Yet another way to reduce the workload of the supervisor is to optimize and improve his work. Can you reduce walking distances? Does he have the tools he needs, and are these tools working well? Quite a few tools from the lean toolbox could be applied here, from 5S to the spaghetti diagram.

This, by the way, is one of the few ideas that work only in one direction. Optimization is there to make things easier or better. Nobody in their right mind would make things intentionally worse just so his people have more workload.

Don’t Split Workers (Too Much)

Another common mistake is to assign the same worker to multiple groups. This is not common on the shop floor, but very common in projects.

Another common mistake is to assign the same worker to multiple groups. This is not common on the shop floor, but very common in projects.

A worker is most effective if he has two or thee projects. Any more than that and the effort of just keeping up to date becomes too much.

Let me give you a real-world example I’ve observed. The leader in question was in charge of three projects. Each project had about forty people assigned to the project. However, the total number of people on all three projects was forty-seven! Even worse, the total number of man hours assigned to the project was the equivalent of thirteen people! If you are now questioning my math skills … well … The average worker was assigned to ten different projects! The average worker was split on ten projects, some of them with this supervisor, others with other supervisors, with roundabout 10% of his time assigned to one project. This is madness!

Just keeping up to date and attending the necessary meetings required more than 10% of the time. The workers did what every sensible worker would do: they picked one or two projects that they worked on, and pretty much ignored the rest.

On the shop floor, similar things happen to supervisors, who often have to do all the improvement projects. A plant I know had about forty-five major improvement projects, but almost all of them relied on a critical shop-floor manager who was also busy with keeping the plant running in the first place. Hence, there was not really any improvement going on. Please don’t make the same mistake, and don’t assign too many projects to a worker.

Don’t Cut the Organization to the Bone

A lot of the problems of overloaded workers come from cost cutting. If you read some of my other blog posts, you may know that I often have a problem with cost accounting. A lot of the work of supervisors and support staff is hard to quantify, and the value is difficult to measure.

A lot of the problems of overloaded workers come from cost cutting. If you read some of my other blog posts, you may know that I often have a problem with cost accounting. A lot of the work of supervisors and support staff is hard to quantify, and the value is difficult to measure.

Traditional cost accounting often has the approach that if they cannot measure it, it must be zero. Hence the value of support staff and supervisors is zero. The cost of an employee, on the other hand, can be measured well. As a result, over the years more and more of this “cost without value”was cut, and many shop floors are running on fumes. (Toyota being again a notable exception).

Consequences of Excessive Workload

Overall, try to have a good workload for your supervisors (and also for your workers). It may not always be easy to determine, as few workers will complain about too little work. It may also be difficult to hire more people, as this will make you unpopular with your own boss (or your shareholders).

If your people are continuously overworked, people will start cutting corners and do sloppy jobs simply because they don’t have time. Eventually, this workload will be seen as normal, and even if you increase the number of people, the “sloppy job is okay” attitude may prevail. Similar effects may happen with underwork (which is common in Japanese offices, where little gets done in an awful long workday).

Now, go out, adjust the workload of your supervisors (and by that I mean reduce, not increase!), and organize your industry!

Thanks, another interesting post. It’s very relevant for me, since I am a production floor team lead. I sympathize with the feeling of having little time for improvement.

Christoph, I wanted to ask for more detail about your comment that “the work of managing other people does not go up linearly.” I’ve done some supervision of teams at several different scales, and this seems plausible based on my experience, but I can’t think of any reasons for this effect. Care to elaborate a little?

Hi Jeremiah, on one hand there is some economy of scale, a meeting for 20 takes not twice the time than a meeting for 10. But on the other hand, you now have many more interactions between people, and less time to manage each of them. A manager should talk with his/her people regularly. The more people there are to manage, the longer the delay between interactions, and the more things have changed since the last interaction, requiring more time to get updated and/or more time to fix things that happened since the last interaction.

Larger groups also trend towards being more occupied with themselves, and “bureaucracy” and “politics” increase, without necessarily a matching benefit.

This may not be the only reason, but I believe that often the diseconomy of scale outweighs the economy of scale in managing larger groups directly.