The Toyota Production System is widely considered to be the best production system for any larger company. Achieving similar performance is the vision (or dream?) of many companies. Pretty much all of lean manufacturing is the attempt to copy the approach of Toyota in the hope of a similar stellar performance. Yet most lean transformations fall way short of the goal. In this blog post I would like to give some insights, from a historical perspective, on why lean so often fails.

The Toyota Production System is widely considered to be the best production system for any larger company. Achieving similar performance is the vision (or dream?) of many companies. Pretty much all of lean manufacturing is the attempt to copy the approach of Toyota in the hope of a similar stellar performance. Yet most lean transformations fall way short of the goal. In this blog post I would like to give some insights, from a historical perspective, on why lean so often fails.

Failure Rates of Lean

Lean is considered to be the best approach to improve your production system, or any other system for that matter (although as a lean expert you could call me biased on that point 🙂 ). Yet, by many accounts, lean projects usually have abysmal failure rates.

Lean is considered to be the best approach to improve your production system, or any other system for that matter (although as a lean expert you could call me biased on that point 🙂 ). Yet, by many accounts, lean projects usually have abysmal failure rates.

Richter claims failure rates well above 50%. Ignizio cites 70%, 90%, or even 95% failure rates. An Industry Week study in 2007 found that almost 70% of all US plants used lean, but only 2% achieved their objectives and a further 24% achieved significant results. Robert Miller from the Shingo Prize committee found that way too many of their past Shingo lean excellence prize winners lost ground and fell behind the competition. (Sources for numbers in this paragraph are at the end of the post.)

These numbers are also consistent with what I see in industry, somewhere around 70% failure rate. I define a failure as a project that did not improve the current situation. (Please note that if I would define failure as a project that failed to impress management with nice numbers on fancy slides, the failure rate would drop rapidly to around 10%–30%.)

Normally, if something fails 70%–90% of the time, we would throw it out and never look back. Unfortunately, the alternative options are usually worse. Much has been written on the reason for these failures, but I would like to look at it from a historical perspective to see where lean went wrong.

The Toyota Production System

Lean originates from the Toyota Production System, which was mostly developed somewhere between 1950 and 1970. The key driver for this was Taiichi Ohno, back then a middle manager responsible for a machine shop. (Read more on Ohno in my post Twenty-five Years after Ohno – A Look Back.)

Ohno had already realized the value of small lot sizes and flexibility earlier during his career. Yet it was in this machine shop where Ohno together with others developed some of the ideas of lean, like pull production, kanban, supermarkets, leveling, and multi-machine handling. Key points to recognize here are:

- Ohno was managing the same shop for years, and knew the details of the work and the workflow.

- Ohno knew the people on the shop floor, including their strength and weaknesses.

- Ohno was able to observe the impact of any changes on the shop floor directly.

- If something did not work, Ohno could not just walk away. Any problems on the shop floor remained his problems until they were solved.

- If a project did not improve the situation, Ohno was able to follow up and to fix the problems (think PDCA).

Through this, Ohno and his people were able to achieve a consistent improvement, and hence he helped to make Toyota the best-organized and most efficient large company in the world.

The United States Takes Notice

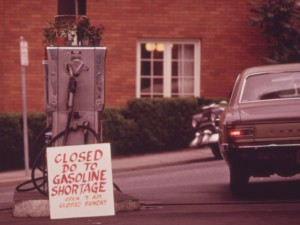

After WW II, US car makers were happily producing like they always had, ignoring the Japanese competition. The US defeated Japan in the war anyway. However, during the 1973 oil shock, US car makers encountered big problems. Customers suddenly preferred more-fuel-efficient Japanese cars over the typical US gas-guzzlers. Even with declining sales, Japanese car makers seemed to handle the problem much better than the US makers, who quickly racked up large inventories of unsold cars.

A famous 1984 study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (and the subsequent book, The Machine that Changed the World, published 1990) found that the US needed twice the manpower to produce a car, much more floor space, inventory etc., while creating many more quality problems while doing so.

There was great interest in how the Japanese and especially Toyota managed their production. Unfortunately, there was no English-language information available on this. Of course, there was much information available in Japanese, but this may as well have been in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. The first English paper about lean appeared in 1977, and only from 1980 onward did written works appear in larger quantities. Yet, merely reading about the Toyota way did not help much. The US needed people with experience.

The First Lean Guru – Shigeo Shingo

One of the first people to arrive in the US with experience at Toyota was Shigeo Shingo. With the help of a US promoter, Shingo soon achieved the status of a guru. However, Shingo was never really an insider at Toyota. To the best of my knowledge, he visited Toyota about once every three months to teach a 4 week workshop on industrial engineering basics called P-Course . He was the moderator for one of the last workshops on SMED (back then known as QDC for Quick Die Change), while the method was already firmly established at Toyota. He tried to learn from Ohno, but met a reluctant Ohno only very few times. Overall, Shingo was probably a small fish among the many people in Japan who worked with or contributed to the Toyota Production System.

One of the first people to arrive in the US with experience at Toyota was Shigeo Shingo. With the help of a US promoter, Shingo soon achieved the status of a guru. However, Shingo was never really an insider at Toyota. To the best of my knowledge, he visited Toyota about once every three months to teach a 4 week workshop on industrial engineering basics called P-Course . He was the moderator for one of the last workshops on SMED (back then known as QDC for Quick Die Change), while the method was already firmly established at Toyota. He tried to learn from Ohno, but met a reluctant Ohno only very few times. Overall, Shingo was probably a small fish among the many people in Japan who worked with or contributed to the Toyota Production System.

Eventually he wrote a book on the “Toyota Production System” (later translated into English as the “Shingo System”). My friends at Toyota have read his books, not because he is famous in Japan (he is not), but only to learn what all the US fuzz about the great lean expert Shingo is about. They were quite disappointed and considered the book not very useful for implementing lean. Some Western lean experts I hold in high regard also agree with this.

Since this book was not authorized by Toyota, Toyota ended the twenty-year relationship, and Shingo moved to the US around 1980. There Shingo now was the one-eyed among the blind, and quickly propelled to guru status. This was helped by a tendency to boast and exaggerate on past achievements he may or may not have had (more on this in my post Shigeo Shingo and the Art of Self-Promotion. More sources also below). His view of lean manufacturing continues to shape what Westerners consider to be “lean,” which is very different from the approach at Toyota.

Lean through External Consultants

Additionally, Shingo was only an external consultant, and hence he approached lean differently than Ohno could as a manager of his own area. While external consultants are needed to bring lean into companies, they face additional challenges compared to a home-grown production system.

Additionally, Shingo was only an external consultant, and hence he approached lean differently than Ohno could as a manager of his own area. While external consultants are needed to bring lean into companies, they face additional challenges compared to a home-grown production system.

External consultants usually neither know the process nor the people very well, at least initially. At the same time, they are often hired as know-it-alls. A consultant that shows uncertainty may not be hired again. This also leads to a proliferation of additional related approaches like, for example, Six Sigma, and adding some more mysticism into the approach.

Unfortunately, lean projects do have uncertainty, and often a lot of it. Contrary to their claims, not all external consultants really know lean very well. Some do, but I also experienced, as a client, completely clueless junior lean consultants who had no idea what they were doing, with little help from higher-ups.

Unfortunately, lean projects do have uncertainty, and often a lot of it. Contrary to their claims, not all external consultants really know lean very well. Some do, but I also experienced, as a client, completely clueless junior lean consultants who had no idea what they were doing, with little help from higher-ups.

Furthermore, US managers are usually pressured by quarterly reports, whereas Toyota managers can have a longer-term outlook. As a result, consultants are often expected to show results quickly.

If you don’t know lean very well, don’t know the process, and don’t know the people, yet have to appear as the one guiding the people to the light, all the while being under time pressure, then you are in a pinch. The common “solution” is often to present a simple method with clearly defined easy steps, like 5S, SMED, or some data gathering like VSM or OEE. While these are powerful methods, on their own and used without context they do not help much. It seems that some lean literature and some consultants try to sell lean as a simple recipe for success, which it is not (see also my post “Lean is Tough” for more).

If you don’t know lean very well, don’t know the process, and don’t know the people, yet have to appear as the one guiding the people to the light, all the while being under time pressure, then you are in a pinch. The common “solution” is often to present a simple method with clearly defined easy steps, like 5S, SMED, or some data gathering like VSM or OEE. While these are powerful methods, on their own and used without context they do not help much. It seems that some lean literature and some consultants try to sell lean as a simple recipe for success, which it is not (see also my post “Lean is Tough” for more).

Often, management is also to blame for accepting a nice final presentation with good-looking numbers over actual performance on the shop floor. Modern managers in my view spend much too little time on the shop floor (Gemba), and way too much in meetings and presentations.

Finally, the consultant may not be around long enough to see the results of the changes, or even fix possible problems (think PDCA again). It is difficult to put a deadline on an improvement project, yet consulting contracts run only for a limited period of time, which is often estimated on the optimistic side.

Finally, the consultant may not be around long enough to see the results of the changes, or even fix possible problems (think PDCA again). It is difficult to put a deadline on an improvement project, yet consulting contracts run only for a limited period of time, which is often estimated on the optimistic side.

In sum:

- A consultant has to impress the client in order to be hired (known as “beauty pageant” in consulting-speak), and appearing to know is often more important than actually knowing.

- Clients often expect quick results, and are unwilling or unprepared for the actual effort of a lean transformation.

- External consultants don’t know people, processes, and products very well.

- Lean often relies overly much on simple methods rather than holistic views.

- Short-term engagements of external consultants make a good PDCA difficult.

There are good and bad consultants out there. But even a good consultant may have problems if the client expects too much in too little time. While I still strongly believe in lean as the best approach to manufacturing, these problems above cause the low performance of many lean implementations.

I hope my view on these historic developments was insightful to you. I also hope that you understand my view of Shingo, and if you disagree (which I would be perfectly fine with), that you are nice about it 🙂 . Finally, I hope that your projects are among the 5%, 10%, or 30% of the successful lean implementations. Now, go out, do some good work, and organize your industry!

P.S.: This post was inspired by a question by T. I.

Selected Sources

- Richter, Lukáš. 2011. “Cargo Cult Lean.” Human Resources Management & Ergonomics 5 (2): 84–93.

- Ignizio, James P. 2009. Optimizing Factory Performance: Cost-Effective Ways to Achieve Significant and Sustainable Improvement. 1st ed. Mcgraw-Hill Professional.

- Rick Pay, “Everybody’s Jumping on the Lean Bandwagon, But Many Are Being Taken for a Ride”, Industry Week, 01-Mar-2008.

- Robert Miller, “Bob Miller Interview with Mike Wall,” Radio Lean, Jul-2010.

- Isao, Kato. Shigeo Shingo’s influence on TPS – An Interview with Mr. Isao Kato. Interview by Art Smalley, April 2006. (Offline, but copies can be googled in some corners of the web).

- Smalley, Art. “A Brief History of Set-Up Reduction: How the Work of Many People Improved Modern Manufacturing.” Art of Lean, 2010.

- Smalley, Art. “A Brief Investigation into the Origins of the Toyota Production System.” Art of Lean, July 2006.

- Smalley, Art. “Eiji Toyoda on the Roots of TPS.” Art of Lean, n.d.

This was a very good observation! I can remember a story that someone told us. They were invited to one of the Toyota manufacturing plants where they observed the TPS and at the end of the visit some of the attendeees stated we need to do this at our plant. One of the tour guides for Toyota then shared some advice. They stated that you do not copy Lean from another company, but need to observe what the PROCESSES are at your plant and use Lean to improve the throughput, increase the quality, and meet your customer’s expectations. Wow what a revelation!

Second, yes management attends too many meetings. The meeting-observations should be where the work is done. Here everyone has a hands-on, real time experience and everyone from the shop floor to all levels of management can understand the FIVE WHYS to where the processes are going wrong. This is truely a team effort from everyone.

Last, you need to be very patient. There are no quick fixes! My suggestion is, if you always done it the way you always have, you will always get what you always got! Bad English maybe, but the right observation. Lean is Kaizen continuous improvement. When Lean is thought of as a three month project, it will surely fail. It took many years to get where you are, take some time to undo and improve your processes. It’s worth the trip!

Great comment, Dennis. Lean seems to be mostly looking “outward” for solutions, whereas Toyota mastered a good mix of outward for inspiration and inward for improvement. Nothing can replace real shop floor visits!

I believe that companies that say they are attempting to become lean fail to do so in the most important ways. I do believe most efforts result in improvement but usually are fairly limited by the existing management system and refusal to really change much.

More than “lean failing” I would say transforming to a different management culture fails. Saying lean fails makes it seem to me that what a lean management system was in use and failed which is not really the case it doesn’t seem to me.

I wrote about these ideas on my blog

https://management.curiouscatblog.net/2012/02/15/why-use-lean-if-so-many-fail-to-do-so-effectively/

and discussed them in this podcast

https://management.curiouscatblog.net/2016/12/07/podcast-building-organizational-capability/

Yay, a comment by the curious cat himself 🙂 I like your blog and read it often. And, in response to your comment, I agree with you.

🙂 I am glad you enjoy my blog.

Many thanks, are greats insights from a historical perspective on why lean so often fails and those could be considered as lessons learned… I really appreciated the statistical numbers and to achieve a consistent improvement lean concept deployment, yes it was insightful for me.

The interesting is that history narratives took me back to the beguinning of 90’s year when I received from my manager a small reading in japonese language, a copy of an apostille, about JIT and TPM to try to make some applications on my on area, it was a big challenge for me on that time but I with my teamwork could understand the meaning by some ilustrations and informations as a guide, that was my first contact with TPS and Lean concepts…

Based on my experience the “Atitude” and the “Cultural changes” are determinating for a successful lean implementation, know the processes and the people are crucial for the desired results with a longer-term outlook, never in a short way. Hence, I also still strongly believe in Lean as the best approach to manufacturing.

The issue is not if IEs make manufacturing work! It is getting everyone involved (teamwork) to solve their problems on the shop floor. The objective is to not only practice the principles of TPS-Lean but to also mentor and teach others. There are only so many IEs that can be carried in a plant and they are also limited if they are torn between issues that arise on a daily basis. SMEs-subject matter experts that are are working where the work is performed should be counted on to use the 5 Whys, Pareto, Cause and Effect diagrams, etc. to find where the process has gone amiss and then experiment-DOE to see if their assumptions were correct. The objective is to be inclusive and not exclusive and to utilize everyone who is involved in the processes utilized so that they can be continuously improved. Just relying on a few for the many is not the TPS or Lean system. That is where America’s manufacturing was back in the 1970s. We need not go back to this model.

some people say that a lean supply chain is a risky supply chain. I understand that JIT and minimal inventories can be risky but not sure what else?

Interesting article. I think we need to look at the word “failure” a little more closely. Most lean efforts do not fail if the definition of fail is did we get better. Most of the time an improvement does get implemented and some of it (but not all of it) gets sustained.

If we alter the definition of failure to “the changes I thought were going to materialize in my business did not happen.” Then the failure rate is much closer to the 70% figure you suggest. This was not only true of lean, but the 70% figure also relates to improvement efforts done under other banners: TQM, Value Engineering and the myriad of other improvement methodologies that have come and gone over the last 40+ years.

There are a host of reasons why. We wrote extensively about this problem in 2010 “Escape the Improvement Trap.” Here are some of the keys:

1. Company A pretty much goes about the business of improvement as Company B, they both get better but from a competitive perspective, nothing much changes.

2. All waste is not important. The most important waste is waste that gets in the way of ‘value creation.’ If value is poorly defined (lacking policy deployment, lacking meaningful strategies, lacking alignment, etc.), then it is impossibly to know which waste to most aggressively pursue. Thus changes get implemented, but nothing meaningful happens. The good news is Company B is going about this exactly the same way.

3. Improvement is seen as belonging to the experts, be they internal black belts, external consultants, or formal improvement teams. There is no rigorous focus on ‘daily improvement, standard work….). Senior leaders hope this improvement stuff will make a difference as we implement improvement ‘projects’ but the business operates as it has in the past. So the culture does not change.

4. It is much safer to be average than it is to try to truly transform. You don’t typically get fired for being ‘average.’ Leaders don’t believe the degree of improvement that is possible. So they don’t fully commit to the discipline needed to do this well.

There are a few others, but I think these cover the keys. It is depressing how few organizations are highly effective at improving. One of the questions I ask on every site visit we do to applicants for the AME Excellence Award is “How do you know you are doing this more effectively today than you were doing it last year?” I don’t care what response I get for any one conversation. But when you talk to a lot of people it is interesting what you can learn about the culture.

Nice article,I feel nothing has been went wrong ,we have to see from angle of change in technology, all the required data we now can see on the screen so manual intervention is less , in other words one or the other tools from 7 QC tool could not be useful but Kaizen , 5S and Muda have no alternative for improvement and excellence in any organization.

Great discussion. As and ex-consultant and now an Operations Management professor, I feel I can weigh in on this topic. My empirical research demonstrated that the vast majority of companies that successfully deploy a Lean Management approach, have invested time and resources in “strategically readying” their organizations for Lean deployment. They cultivate executive leadership, supervisory level leadership, institutional culture and climate as well as lean skills in concert to prepare the organization, and as such have higher degrees of Lean Competency and realization of Lean benefits. Organizations that take a “just-do-it” approach to Lean implementation, without adequate investment time and resources to prepare the organization, are typically disappointed in their results. Unfortunately, they blame Lean and not their lack of preparation as the root cause of their disappointing results.

I am currently on a lean manufacturing team with my company now. The scope of the project is huge! I do not see how we will ever implement this type of style into or company tho. We have so much variation with in our facility. We are not creating the same exact product over and over. We are like burger king. The customer has it their way. We are more like a job shop. A job shop that does 15mil. a month. I have little hopes for this project. I am all ears tho and sure we will take something from it. I’m not sure we will see the gains they are showing in predictions. NVAT/VAT can we reduce this can we better that? yes. Can we make it one line and expect it to flow in such a manner? I do not see this. We have some process that take 12 hrs to complete. This will be interesting to see tho.

A good read – I will be sharing this.

One of the things that struck me the most was how personal it was. It wasn’t (as you say) an external person coming to ‘make change’, it was someone who knew and cared from the inside…

I have heard that’s one of the problems we are having with capitalism, in previous eras the ‘owners’ were present and much more connected with the impact of their actions, decisions…

Lean is first of all a culture. A culture of having front line employees participating in continuously improving operations. External Consultants or distant Managers can’t change the culture.

In my opinion, the failures come from misunderstandings of TPS. For example, Toyota people and Ohno explained TPS consists from 2 pillars (JIT and Jidoka). When I studied TPS, I had a big doubt about these “2”, and thought that “2” are really major pillars? After the study, finally I found the right answer (Japanese book by Professor Hiroaki Satake, retired). He pointed out: The pillars of TPS are “Pull” and “Multi-Process Handling”. If my opinion is right, the failures come from the wrong explanation by Toyota people and Ohno, because when people studied TPS and implemented improvement project, they must stick to JIT and Jidoka and set “2” as major points of the project.

I guess if the people implement the project 1) Based on their situations, 2) Understanding of TPS, fully and deeply, 3) Take step-by-step method, the failre rate must be low.

Of course, Toyota people and Ohno have (had) the rigt for explanation of TPS.

Dear Osamu, very good comment. It happens to be that JIT and Jidoka are “invented” by members of the Toyoda family. Toyota is working on increasing the fame of their own family members, and this is probably why these two were chosen. I do like your (or Prof. Satake’s) point much more. I was also thinking about what the key elements of the Toyota production system are, but I do not (yet) have a definite answer.

Very help full detail.