FiFo lanes are an important part of any lean material flow. They are a very simple way to define both the material flow and the information flow. In this post I want to tell you why to use FiFo, how to use FiFo, and the advantages of FiFo, as well as show you a few examples of FiFo lanes.

FiFo lanes are an important part of any lean material flow. They are a very simple way to define both the material flow and the information flow. In this post I want to tell you why to use FiFo, how to use FiFo, and the advantages of FiFo, as well as show you a few examples of FiFo lanes.

The Reason for FiFo – Decoupling of Processes

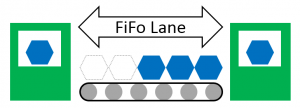

Processes usually have different cycle times needed to process one part. Hence processes have to wait for slower processes. In a static world with no fluctuations or variations, this would never change, and the processes would always have to wait on the slowest process, (i.e., the bottleneck). No amount of inventory in between will change that.

Imagine three processes as shown below, where the middle process is always the slowest one. All inventories before are always full, and all the upstream processes are blocked. Similarly, all the inventory afterward is empty, and all processes downstream are starved for material. Again, no amount of inventory in between will change that.

However, in the real world, processes are not static but dynamic. Sometimes a process will take longer or shorter time than average. In this case, a FiFo lane can improve utilization and throughput of the system. For that matter, any type of buffer can improve the system, although the FiFo lane has quite some advantages as we will see below.

However, in the real world, processes are not static but dynamic. Sometimes a process will take longer or shorter time than average. In this case, a FiFo lane can improve utilization and throughput of the system. For that matter, any type of buffer can improve the system, although the FiFo lane has quite some advantages as we will see below.

Ideally, the process with the slowest average speed should never have to wait on another process (either from lack of material or from being blocked). However, due to such fluctuations, the process may have to wait because another process is temporarily slower. This waiting can be avoided by having inventory, with the long-term slowest process working with material from a buffer inventory (if the temporary slower process is before), or filling into a buffer (if the temporary slower process is afterward).

The picture below shows you the examples, where the last process is temporarily slower and the middle process works into the empty inventory, and where the first process is temporary slower and the middle process works out of a full inventory.

Again, this works for any kind of buffer. A FiFo lane, however, does have some advantages. But first I would like to talk about what makes a FiFo lane a very special type of inventory storage.

The Rules for FiFo

There are basically two rules that are important for FiFo lanes:

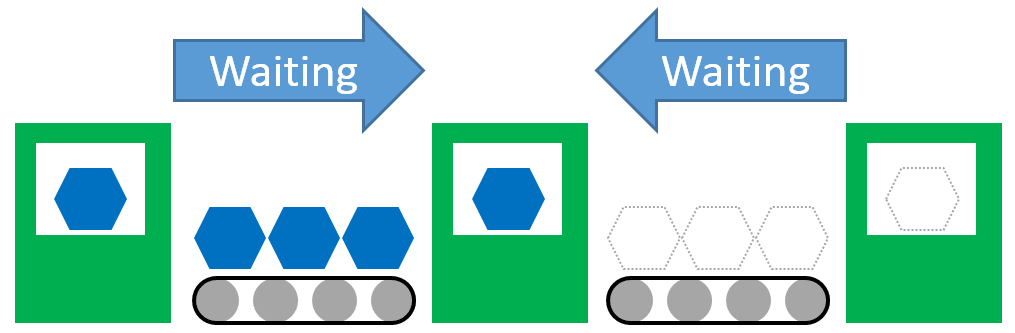

No part can overtake another part

The first part that goes into the buffer is also the first part that comes out, hence the name FiFo for First-In-First-Out. The sequence of parts has to be maintained. No part can overtake another part in the lane. No part can squeeze in from the outside either.

This rule is important to avoid fluctuations in throughput time. One of the goals of lean manufacturing is to have a smooth material flow. If parts overtake each other, then the waiting time for the other parts will be longer, and can potentially be much longer. Eventually the delayed parts will be too late too.

Imagine you’re standing at the supermarket checkout, with ten people in line in front of you. While it may take some time, you can estimate how long it will take you to pay and leave. Now imagine someone cutting in line in front of you. Certainly, you will have to wait longer. Now imagine every third person cutting in line in front of you. Your waiting time can be very unpleasant.

Imagine you’re standing at the supermarket checkout, with ten people in line in front of you. While it may take some time, you can estimate how long it will take you to pay and leave. Now imagine someone cutting in line in front of you. Certainly, you will have to wait longer. Now imagine every third person cutting in line in front of you. Your waiting time can be very unpleasant.

While in manufacturing parts won’t get upset if they wait in line longer, the customers waiting for the parts certainly will (as will your friends and family if you do not show up with the groceries).

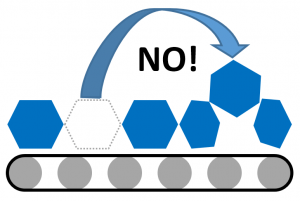

There must be a clearly defined maximum capacity

The second rule requires the FiFo lane to have a clearly defined maximum capacity. There must be an upper limit, after which the preceding processes have no more space in the lane to put parts and must stop. When the FiFo is full, the preceding process must stop.

By the way, there is no explicit rule for a minimum capacity. The minimum capacity of a FiFo lane is zero. Since it is impossible to have less than zero parts in the lane, we need no extra rule to cover impossible cases. If there are no parts, the next downstream process has to stop.

The reason for this rule is to avoid overproduction. Overproduction is one of the seven types of waste (Japanese: muda), and according to common wisdom it is the worst type of waste. If you produce too much, your system will be clogging up. Everything will be slower, waste increases, throughput time increases, and your system will be anything but lean.

Breaking the Rules

As always, some rules can be bent and others can be broken. The two rules above are what turns a buffer into a FiFo lane. These rules make a lot of sense and should be followed. However, there may be rare cases where it may make sense to break the rules. Just be fully aware that by breaking these rules you will create some problems elsewhere that you can not yet even see. The question is, is it worth it?

For example, assume you have different products on your FiFo lane and you are missing parts to process the next two products on the lane (they won’t arrive until three days later). Now you have two options:

- Wait until the missing parts arrive three days later.

- Take the products off the FiFo lane (and hence change the sequence).

Purists would say that you must not break the rules. Practice has taught me that sometimes it may be necessary to break the rules. In the example above I would break sequence and take the two products that I cannot process off the line and continue with other products. After the missing parts arrive, I would put the products back in the FiFo, possibly even jumping ahead in the line.

Let’s be clear: I don’t like it. However, I would like it even less to stop production for three days until the parts arrive.

At the same time, be careful not to make too many exceptions. You mess up your system, you teach your employees that rules in general are only optional, and worst of all you take pressure off the system to improve. Hence avoid breaking the rules as much as you can.

Advantages of FiFo Lanes

A FiFo lane has quite some advantages. First of all, it is a clearly defined material flow. You avoid overproduction and stuffing your system since the upstream process must stop if a certain inventory limit is reached (the downstream process stops anyway if the buffer is empty). Fluctuations on throughput time are reduced, and it is more likely that your parts will be completed on time. No part will be forgotten in the system until it is too late, with either the customer complaining or the part becoming old or obsolete.

It is a lean material flow. Due to the upper limit on FiFo lanes, it is not possible to overfill the system. Your system will still be able to react (relatively quickly) to changes in demand. Your total work in progress and inventory is capped. All seven types of waste (of which overproduction is the worst) will be reduced. Overall it is more efficient.

It is also a clearly defined information flow. You do not need to tell the processes at the end of the FiFo line what to do. They simply process whatever part comes down the lane. This takes a lot of management overhead off your chest. You only need to control the first process in a FiFo system; all the others manage themselves (at this point, Kanban are very useful to control the first process).

FiFo also helps visual management. It is usually easy to see if a FiFo lane is full or empty, giving you lots of clues on the status of the system, as for example the bottleneck. If you or your employees notice the FiFO getting rather full or unusually empty, they may investigate why and may be able to fix a problem before it becomes critical. Never underestimate the ability to go and see directly what is going on in your system.

Examples of FiFo Lanes

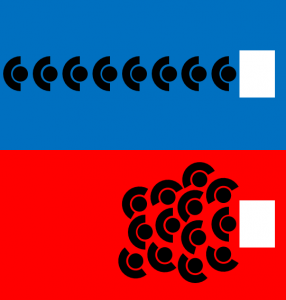

Finally, I have a few examples on FiFo lanes. One example that probably all of you have experienced at one point or another is waiting with other people for a process. This may be at the supermarket checkout, airplane check-in, the ticket window, the toilet, a fast food counter, or any kind of one-person-at-a-time service. Hopefully for you, the system utilized a FiFo lane. This is probably the most fair approach. Which of the two queues below would you rather be in?

Below is another example, the assembly line. The number of parts in the line is limited, and the parts – in this case the cars – don’t overtake each other.

Below is one of the first assembly lines in the world: the line of Henry Ford producing his model T, or in the image below the magneto line.

I hope this post on the FiFo lane was interesting to you. The mathematical details are in my next post Determining the Size of Your FiFo Lane – The FiFo Formula, and there is also a FiFo Calculator – Determining the Size of your Buffers. Now go out and organize your industry!