In my last post I looked at the preparations for a proper ramp-up or start of a machine or process. This post is the second part where you actually press the button and start the machine. I will also discuss the ramp-down procedures, as well as a SMED-like approach to improve the ramp down and up again process.

In my last post I looked at the preparations for a proper ramp-up or start of a machine or process. This post is the second part where you actually press the button and start the machine. I will also discuss the ramp-down procedures, as well as a SMED-like approach to improve the ramp down and up again process.

Ramp-Up: Starting the Process

Now you can finally start the machine. For a small machine this may simply switching it on. For larger machines this may be a multi-step operation. This may include warm-up processes, starting auxiliary engines and control systems, before starting the main process. It may also include setting up the part to be processed. There may also be some waste, as the first parts may not be of good quality. For example, in injection molding the first parts are often scrap due to smaller temperature differences. In some cases the first parts may also be produced slower than normal.

Now you can finally start the machine. For a small machine this may simply switching it on. For larger machines this may be a multi-step operation. This may include warm-up processes, starting auxiliary engines and control systems, before starting the main process. It may also include setting up the part to be processed. There may also be some waste, as the first parts may not be of good quality. For example, in injection molding the first parts are often scrap due to smaller temperature differences. In some cases the first parts may also be produced slower than normal. Very often this also involves some quality checks. The first few presumed good parts are checked for accuracy and quality. If by any change there was an error in the set-up, you would like to know it as soon as possible before jugging an entire shift worth of production into the bin. These quality checks can be formal (i.e., a 3D measurement machine) or informal (does the machine sound/smell/feel all right?) or both.

Very often this also involves some quality checks. The first few presumed good parts are checked for accuracy and quality. If by any change there was an error in the set-up, you would like to know it as soon as possible before jugging an entire shift worth of production into the bin. These quality checks can be formal (i.e., a 3D measurement machine) or informal (does the machine sound/smell/feel all right?) or both.- Once the process is running properly, you can already put your attention on the next job. What (if any) is the next job, what material and tools do you need?

Now your machine should be up and running safely, efficiently, and with good quality.

Ramp-Down

The ramp-down has a lot of similar steps, but in reverse.

The ramp-down has a lot of similar steps, but in reverse.

- After you have completed the current part, you should turn off the machine. Again this may be an easy switch or a more complicated cool-down process, purging of leftover material (e.g., an injection molding screw), and shutting down multiple systems and computers.

- Depending on the duration of the shut-down, you may have to add covers and other parts for a longer idle time (think “Remove before Flight” tags again).

- Cleaning: Don’t leave a mess behind, not in public and not at work. Clean the machine, and remove dirt, oil, chips, and anything else so the next operator has a clean machine to start with. If the process involves glue or foam, is there a foam nozzle that needs to be removed and the machine cleaned?

- Again Maintenance: Are there any steps needed for maintenance? Do some movable parts need to be oiled? Do some parts need to be exchanged? Some processes also benefit from a visual inspection.

Not popular but necessary is Documentation. Fill out the information (paper or digital) on the product and/or the process. This will help the next operator in starting the machine, and can provide valuable clues when eliminating quality issues or searching for improvement potentials.

Not popular but necessary is Documentation. Fill out the information (paper or digital) on the product and/or the process. This will help the next operator in starting the machine, and can provide valuable clues when eliminating quality issues or searching for improvement potentials.

Creating and Improving Ramp-Up and Ramp-Down

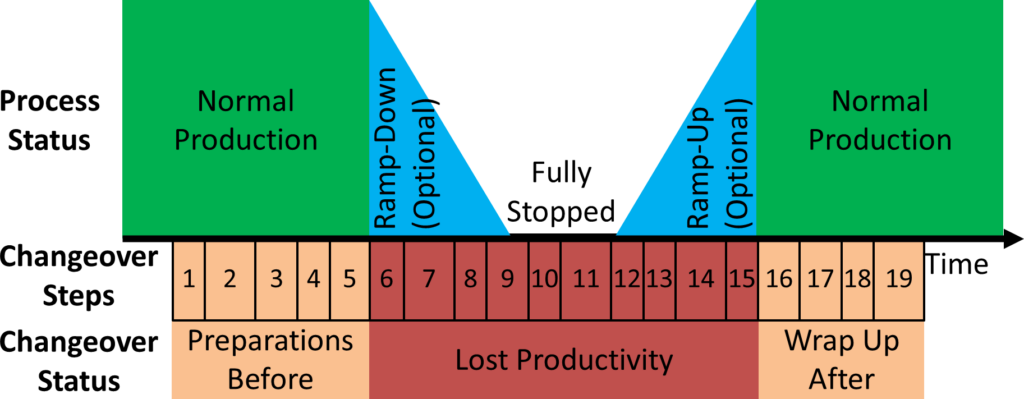

There is no explicit tool for improving the ramp-up and ramp-down procedures, but it is basically the same as SMED for changeovers, except without the changeover. Of course it could also include a changeover if needed.

- Like a normal SMED process, you first observe the ramp-up and ramp-down procedures to get a list of tasks and their duration. This observation as well as the following steps are best done as a multi-functional group, including at least one operator for the process and if necessary one technical expert if it is a larger machine. This list should include everything that is part of the ramp-up and ramp-down procedures.

- Slightly different from SMED, you should also evaluate if these steps are good, or if they could have a negative impact on safety or quality. If so, please improve the steps until you are certain that it is safe to make good parts. This is not explicit a part of SMED, but SMED would benefit from this too. Often it is done somewhat automatically when doing a SMED workshop. I have listed it here separately since chances are there has not been a detailed analysis of the ramp-up and ramp-down procedures before.

- Some of these steps will be when the machine or process is already slowed or stopped. These would be the internal processes where we lose productivity. Similar to SMED, we look at which internal procedures can be moved to external procedures. This will increase the overall time available for production. If you can move an internal step to external, it is usually worth it even if it takes longer externally.

- Again similar to SMED, see if you can shorten the internal and external procedures.

- Now you verify if these new updated steps are good. If possible try it out, maybe even more than once.

- Finally you create a standard and train the operators.

When to Standardize the Ramp-Up and Ramp-Down

Creating and following a standard for a ramp-up and ramp-down procedure is work. As with all standards, you should create a standard if the benefit of a standard exceeds the effort of creating, establishing, and maintaining a standard. Unfortunately, as all so often in lean, the benefit is there but hard to measure. If a failed ramp-up breaks your parts or—worse—your machine, you will regret not having it. Hence, you would need to estimate if it is worth the effort. Also, in lean, people often underestimate the benefit.

Creating and following a standard for a ramp-up and ramp-down procedure is work. As with all standards, you should create a standard if the benefit of a standard exceeds the effort of creating, establishing, and maintaining a standard. Unfortunately, as all so often in lean, the benefit is there but hard to measure. If a failed ramp-up breaks your parts or—worse—your machine, you will regret not having it. Hence, you would need to estimate if it is worth the effort. Also, in lean, people often underestimate the benefit.

Personally, I would go for machines and processes where I either have capacity issues, a history of problems due to the ramp-up and ramp-down, or a major worry that there will be problems due to the ramp-up and ramp-down. This is a choice you have to make.

Summary

Overall, ramping a process up and down well impacts quality, safety, and efficiency. Key for success is to educate your operators. There should be no rush to produce, but the goal should be to produce good quality safely. Now, go out, get the starting and stopping of your processes in order, and organize your industry!

PS: This post was insipred by a visit to LISI Aerospace in Saint-Ouen-l’Aumône as part of the Van of Nerds in France tour 2022 as well as a question by Joel Gomez