This post looks at more plants we visited on our Van of Nerds tour in France in 2022. The focus this time is the aircraft industry, in particularly the engines. We visited a major maker of aircraft engines, or their nacelles and thrust reversers to be more precise, Safran in Le Havre. But we also visited two suppliers for engine components. LISI specializes in high-performance bolts and screws for aircraft, but also has some highly advanced digital displays on their shop floor. JPB makes well-designed inspection ports for aircraft engines, for which they developed some really clever digital solutions, which they now also provide to others. It was definitely a set of highly interesting visits. Let me show you!

Safran Nacelles in Le Havre

Safran is a French company with 77 000 employees that design and produce aircraft engines, rocket engines, and other equipment that can fly. One of their subdivisions is Safran Nacelles. The nacelle is the structure that cover the engine, attached to the aircraft. It channels the engine’s airflow, brakes the aircraft during landings, through its built-in thrust reverser, and reduces noise of the engine. The factory goes back to a workshop from 1896, but became Safran only in 2005 after a merger of two other companies ( SNECMA and SAGEM).

Safran is a French company with 77 000 employees that design and produce aircraft engines, rocket engines, and other equipment that can fly. One of their subdivisions is Safran Nacelles. The nacelle is the structure that cover the engine, attached to the aircraft. It channels the engine’s airflow, brakes the aircraft during landings, through its built-in thrust reverser, and reduces noise of the engine. The factory goes back to a workshop from 1896, but became Safran only in 2005 after a merger of two other companies ( SNECMA and SAGEM).

Like most aircraft plants, I was struck by the cleanliness of the location. We looked in detail at the building of nacelles, their carbon-fiber composite operations, and their thrust reverser assembly line. The assembly line was particularly interesting. They build the two halves of a thrust reverser in parallel on an assembly line with seven stations. A robotic arm lifted the huge half thrust reverser, and was able to position it exactly where the operator wanted it. These robotic arms were on wheels, and could move to the next station when completed. In fact, it was a continuously moving assembly line, although at 5 millimeter per minute the movement was not really visible.

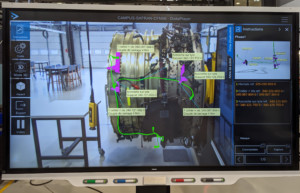

Like many low-volume flow lines, the time at one station is roughly one shift, as this makes the assignment of workers much easier (see also Trumpf). At Safran, the takt was seven hours. They also matched supply with demand by having idle stations for one shift. It is hard to remember seven hours’ worth of tasks, and a good work standard including the documentation of all completed tasks was necessary. Hence, particularly interesting was that they used augmented reality for the operator instructions. This was exactly the system we saw earlier at the CampusFab (photo shown here). It was really cool to see this actually used in action, although it was at the time of our visit only the final test before full implementation. Overall an impressive plant.

LISI Aerospace in Saint-Ouen-l’Aumône

LISI Aerospace with 5500 employees dates back to a clock factory in 1777, which turned into a screw factory, and now into a company specializing in fasteners for the aircraft industry. You could call them screws, but these are anything but your ordinary hardware store bolts. These are high-end, ultra-lightweight marvels of material science and engineering. A typical aircraft has over 10 000 types of fasteners.

LISI Aerospace with 5500 employees dates back to a clock factory in 1777, which turned into a screw factory, and now into a company specializing in fasteners for the aircraft industry. You could call them screws, but these are anything but your ordinary hardware store bolts. These are high-end, ultra-lightweight marvels of material science and engineering. A typical aircraft has over 10 000 types of fasteners.

Compared to other companies I visited, the material flow was much less complex. Instead of assembling complex parts, they merely cut a piece off a titanium rod and machine it into a screw. Each part went through only a few steps before completion. Despite all the machining, it was an extremely clean plant. They have on average one week worth of material inbound, and one week worth in production.

Compared to other companies I visited, the material flow was much less complex. Instead of assembling complex parts, they merely cut a piece off a titanium rod and machine it into a screw. Each part went through only a few steps before completion. Despite all the machining, it was an extremely clean plant. They have on average one week worth of material inbound, and one week worth in production.

But what impressed me the most was their digital integration. They had highly advanced digital shop floor boards that were well integrated with the machine data, and used by the operators. This was for me such an important topic that I plan to write a separate article on shop floor boards. LISI uses the software from a startup called Fabriq, although I found it surprising that the data is also hosted at the software vendor.

But what impressed me the most was their digital integration. They had highly advanced digital shop floor boards that were well integrated with the machine data, and used by the operators. This was for me such an important topic that I plan to write a separate article on shop floor boards. LISI uses the software from a startup called Fabriq, although I found it surprising that the data is also hosted at the software vendor.

Another personal highlight for me was their use of CONWIP. CONWIP is a way to do pull production for make-to-order products. Even though LISI makes screws, these are high-end screws often make-to-order instead make-to-stock. Hence, since 2017 they decided to use CONWIP. As the author of the bible on pull, “All About Pull Production,” I was very happy to see this type of pull system so well implemented.

JPB Système in Montereau

JPB Système is a small, family-owned company with around 150 employees, that started in 1995. They make self-locking for-access ports for borescopes to inspect aircraft engines. It is basically a screw that closes the hole for the borescope without the need for any extra anti-vibration locks. After the founder passed away in 2006, the son took over, bringing a very interesting set of qualifications along. He studied programming, but had to get familiar with the mechanical engineering side of the business. Hence, he is comfortable both in the mechanical and the digital world, which was clearly visible on the shop floor.

JPB Système is a small, family-owned company with around 150 employees, that started in 1995. They make self-locking for-access ports for borescopes to inspect aircraft engines. It is basically a screw that closes the hole for the borescope without the need for any extra anti-vibration locks. After the founder passed away in 2006, the son took over, bringing a very interesting set of qualifications along. He studied programming, but had to get familiar with the mechanical engineering side of the business. Hence, he is comfortable both in the mechanical and the digital world, which was clearly visible on the shop floor.

For one thing, he was able to bring the different data structures of the different machine makers under control (no easy task, I tell you) and integrate them all into a digital shop floor display. I will talk more about this in an upcoming posts on digital display boards.

Another very neat feature was the use of vibration sensors. They developed a small computer that is simply attached to the side of the machine using magnets. This KeyProd system has a vibration sensor and simply measures the vibration of the machine. With two learning cycles, algorithms can understand the proper operations of the machine, and from then onward track the machine status. It can count the pieces, analyze an OEE, and even detect micro stops—which are usually very tough to analyze. By simply sticking this digital brick to the side of a machine they can bring an old machine into the digital world. They can also bypass complicated different machine databases and integrate the machine status on the same data platform. I found this so impressive that I plan to write a longer blog post on this too, as a simple paragraph won’t do justice to the possibilities from this gadget.

Another very neat feature was the use of vibration sensors. They developed a small computer that is simply attached to the side of the machine using magnets. This KeyProd system has a vibration sensor and simply measures the vibration of the machine. With two learning cycles, algorithms can understand the proper operations of the machine, and from then onward track the machine status. It can count the pieces, analyze an OEE, and even detect micro stops—which are usually very tough to analyze. By simply sticking this digital brick to the side of a machine they can bring an old machine into the digital world. They can also bypass complicated different machine databases and integrate the machine status on the same data platform. I found this so impressive that I plan to write a longer blog post on this too, as a simple paragraph won’t do justice to the possibilities from this gadget.

They also set up their plant to run two shifts. A third night shift is fully automated, and no workers are present. After the workers refill the material at the end of the second shift, they leave, and the system runs on its own till morning (with the occasional shut down due to a problem). Overall a highly impressive and dynamic company.

Altogether, the van of nerds in France was a huge success. Special thanks to nerds Franck Vermet and Michel Baudin for organizing the sites. I will definitely write a few more blog posts in the future on some details we learned from this tour (e.g., on dashboards and vibration technology). Now, go out, keep on reading, and organize your industry!

PS: Fellow Nerd Michel Baudin (and Cécile Roche) has also written about the trip. Here are his blog posts, check ’em out for a different view of the same tour 🙂