Work standards are a key component to continuous improvement. A standard is a tool that (if used correctly) prevents drifting away from a best-practice approach to do a task. Hence, I sometimes read that everything needs a standard. However, I don’t quite fully agree with this. Let me tell you when standards are helpful, and when maybe not.

Work standards are a key component to continuous improvement. A standard is a tool that (if used correctly) prevents drifting away from a best-practice approach to do a task. Hence, I sometimes read that everything needs a standard. However, I don’t quite fully agree with this. Let me tell you when standards are helpful, and when maybe not.

Introduction

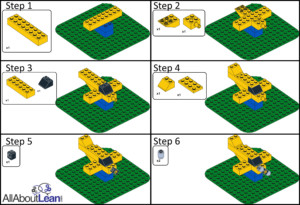

I have written an extensive nine-post series on work standards, in addition to the related standard work for organizing the process sequence. The objective of a standard is to provide a clear depiction of a task, deconstructing it into distinct stages. It ought to encompass all relevant elements, with a particular emphasis on those linked to safety and quality. A standard can encompass visual aids, textual explanations, or a combination of both. While it should include all necessary details, it also should strike a balance between too much and too few details.

I have written an extensive nine-post series on work standards, in addition to the related standard work for organizing the process sequence. The objective of a standard is to provide a clear depiction of a task, deconstructing it into distinct stages. It ought to encompass all relevant elements, with a particular emphasis on those linked to safety and quality. A standard can encompass visual aids, textual explanations, or a combination of both. While it should include all necessary details, it also should strike a balance between too much and too few details.

When to Use or Improve a Standard

Work standards are best for repeatable processes. The higher the repeatability, the easier it is to write a standard. It is said that a good takt for a standard is between thirty seconds and two minutes. For a longer takt you need to draw more on the experience of higher-skilled operators. For example, machine tools and airplanes often have a takt of eight hours or more.

Work standards are best for repeatable processes. The higher the repeatability, the easier it is to write a standard. It is said that a good takt for a standard is between thirty seconds and two minutes. For a longer takt you need to draw more on the experience of higher-skilled operators. For example, machine tools and airplanes often have a takt of eight hours or more.

Standards are most frequently written or improved to solve a problem. Where in your area of responsibility are your biggest problems with repeatable tasks? Is it quality? Cost? Time? Or, hopefully not, safety? If you have multiple possible standards that you could or should write, I find an impact effort matrix helpful. Estimate the possible impact of the improved standard versus the effort to achieve it. Select a problem that is relevant and gives a good benefit for the invested effort.

Standards are most frequently written or improved to solve a problem. Where in your area of responsibility are your biggest problems with repeatable tasks? Is it quality? Cost? Time? Or, hopefully not, safety? If you have multiple possible standards that you could or should write, I find an impact effort matrix helpful. Estimate the possible impact of the improved standard versus the effort to achieve it. Select a problem that is relevant and gives a good benefit for the invested effort.

In the (hopefully not too) long run, of course, every repeatable process of some complexity should receive a standard. Here, too, you should start with the most critical processes where a standard could give you the best improvement for the effort.

When (Probably) NOT to Use a Standard

Standards aim to improve your processes. In a perfect world, all of the actions going on in your shop floor have standards. In a perfect world, these are updated and improved at regular intervals. I read every now and then the advice to standardize everything. But this is not good.

Instead, this is wishful thinking. Realistically, you probably don’t have time to write all of these standards, let alone improve them regularly. Standardizing the cleaning service emptying your trash can have potential, but you may have more pressing issues at hand (albeit the guy emptying my trash can during my sabbatical at Keio University had some serious skills!).

You should not write a standard for a process that is not repeatable or has high variability between repetitions. Standards describe a set of actions. The more these actions differ at every interval, the fuzzier a standard will be. If you assemble a car engine, you can have detailed standards for every step. If you design a new car engine, you have at best some high-level standards, but all the details of the problem solving and product development cannot reasonably be standardized. One common task that is hard to standardize is leadership and management. Managers solve problems and make decisions, but these vary every time. A standard like the common buzzword “leader standard work” is at best a high-level checklist like “attend the shop floor meeting every day,” but this is a far cry from a proper work standard.

You should not write a standard for a process that is not repeatable or has high variability between repetitions. Standards describe a set of actions. The more these actions differ at every interval, the fuzzier a standard will be. If you assemble a car engine, you can have detailed standards for every step. If you design a new car engine, you have at best some high-level standards, but all the details of the problem solving and product development cannot reasonably be standardized. One common task that is hard to standardize is leadership and management. Managers solve problems and make decisions, but these vary every time. A standard like the common buzzword “leader standard work” is at best a high-level checklist like “attend the shop floor meeting every day,” but this is a far cry from a proper work standard.

Very related are tasks that use significant human creativity. If you are an artist like a painter or sculptor, you may have some standards on how to prepare the paint or set up the marble. However, the actual creation of the art is an act of creativity. If you want to standardize this process, you better get a copy machine or a printer rather than an artist.

Very related are tasks that use significant human creativity. If you are an artist like a painter or sculptor, you may have some standards on how to prepare the paint or set up the marble. However, the actual creation of the art is an act of creativity. If you want to standardize this process, you better get a copy machine or a printer rather than an artist.

Similarly, standards are not always helpful for tasks with very low repetitions. Creating and maintaining a standard is a lot of work. The benefit comes from using the standard repeatedly. If you use the standard only a few times, you may get little benefit out of the creation of the standard. In the extreme case, if you produce a part only once, you may not even be able to do a proper standard, as you would need repetitions to improve the standard.

Similarly, standards are not always helpful for tasks with very low repetitions. Creating and maintaining a standard is a lot of work. The benefit comes from using the standard repeatedly. If you use the standard only a few times, you may get little benefit out of the creation of the standard. In the extreme case, if you produce a part only once, you may not even be able to do a proper standard, as you would need repetitions to improve the standard.

However, standards can be part of individual processes within a larger process. If you build yourself a custom house, the installation of the electricity and other building codes are of course a standard. However, you would not write a detailed standard on how to create the entire house besides the blueprint. Furthermore, in some cases the impact of the standard on quality and performance can be so significant that standards sometimes are created even for very few repetitions. The Saturn V moon missions had detailed standards and procedures for the entire production process and many eventualities, and the participants were trained in the use of these standards. However, this was also insanely expensive, with multiple rockets launched for the development process before actually landing on the moon.

Finally, and probably the most common reason for not writing a standard is a lack of resources—or more properly, the decision to invest the resources into more pressing problems. If a consultant advises you to standardize everything, they don’t have to do it themselves and won’t foot the bill (on the contrary, they write a bill for you). As a manager, you will always have limited resources on time, manpower, money, and material. You have to decide where to invest these resources to generate the best benefit for the company. A lot of these resources will go into development and production. Hopefully a significant chunk will also go into improvement. Administration will also hog (more and more of?) these resources. Standards can help you to solve problems and maintain the (current) best practice. But you don’t have the resources to solve all problems. Start with the most urgent ones, and postpone the less pressing issues to a later day. It would be nice to have a good standard for emptying the trash can, but it is probably not the most urgent issue on your agenda.

Finally, and probably the most common reason for not writing a standard is a lack of resources—or more properly, the decision to invest the resources into more pressing problems. If a consultant advises you to standardize everything, they don’t have to do it themselves and won’t foot the bill (on the contrary, they write a bill for you). As a manager, you will always have limited resources on time, manpower, money, and material. You have to decide where to invest these resources to generate the best benefit for the company. A lot of these resources will go into development and production. Hopefully a significant chunk will also go into improvement. Administration will also hog (more and more of?) these resources. Standards can help you to solve problems and maintain the (current) best practice. But you don’t have the resources to solve all problems. Start with the most urgent ones, and postpone the less pressing issues to a later day. It would be nice to have a good standard for emptying the trash can, but it is probably not the most urgent issue on your agenda.

Having said that, please do not use my words as an excuse to avoid standards. Standards are VERY helpful and useful, and not using standards at all would be gross neglect in most cases. If you lack the resources for creating standards everywhere, it merely means that some standards will be created later than others. I am merely trying to help you to figure out where to best use standardization, and where probably not. But YOU DO NEED STANDARDS! Now, go out, set up standards where they are sorely lacking, and organize your industry!

Excellent treatment of the topic!!

Thank you Christoph for your article.

This is a subject of contention in the plants I work in when it comes to maintenance activities.

When we have a safety event (near-miss or accident) involving one of our technicians performing a maintenance task, almost always one of the root causes is a lack of standardized work.

And while we invest in documenting, there is always a lot of detail that gets inevitably missed.

Your article touches on reasons why this is a challenge for us, so thanks again.

Best Regards,

Brandon

Well done as usual. I have seen too many consultants try to place work standards on processes that are not repeatable or have lots of time between processes.

In the end, everything should have a standard, whether it is written or spoken. However, it is not as complicated as it seems. Yes, repeatable, predictable processes get a formal write-up (combo/spaghetti charts) and are given priority over other less repeatable processes.

A sheet of pictures of the high-level steps will suffice for very long cycles over many days or for a very high mix/low volume facility.

Jobs such as maintenance should have check sheets of a preventative nature at critical timeframes. Involve equipment manufacturer reps and process engineers to ensure nothing is overlooked on the check sheet. Review breakdown data trends to guide timing/frequency and areas to check. Make sure it is reviewed to ensure it is being followed. One maintenance Supervisor I knew used to take apart a few pieces of machinery, i.e., panels, and place a small piece of paper with the word “coke” written on it. He then told his people if they brought him the piece of paper, he would give them what it said. This is how he ensured critical checks were being performed (or not).

Process engineers should have engineering change logs and boundary samples.

No “standardized work” documentation needs to exist if many things a person does have individual standards, i.e., the proper way to label secondary containers, a picture in a conference room showing how it should be left, a visual JSA, One-Point Lessons, or other activities guided by policies.

If resources are an issue, start by borrowing a standard from somewhere else and modifying it as necessary. Ask vendors and supplier reps for help in establishing a standard. Ask your connections on Linkedin. Some state agencies provide this kind of service for free, i.e., https://www.okalliance.com/. Ask the person doing the job to write down the key steps in sequence, with a time for each step.

One of the reasons there are so many meetings at many companies is due to a lack of standards – primarily the reason they call a meeting – to get everyone’s input or buy-in before something is done. If a standard existed, they wouldn’t need a meeting – they could refer to the standard and get on with their life.

Everything should have a standard (if you want to have a sane, productive, and more satisfying work life).

“One common task that is hard to standardize is leadership and management.”

Probably. But I would suggest that work standards are a way of regulating or controlling the behaviour of those lower down the pecking order; those “below the salt”. Lean and Lean consultants have not found a way of regulating leadership behaviour for the better. Perhaps it is hard, but I suggest there are ways by which the leader, like Caeser’s wife, is seen to understand the importance of standards by voluntarily regulating his or her behaviour. For example, some of the Lean tools could be applied to leaders and managers: Kamishibai Boards which are publically displayed so everyone knows where he or she is.

Then there is the wider definition of standards which should address the minimum levels of skill that should be achieved by anyone who is responsible for the well-being and development of others. There is some whispering in the Lean galleries about mentoring and coaching that should be brought centre stage. Can the CEO or the first-line supervisor demonstrate a world-class (the minimum) ability to coach someone else with their change proposal in the form of Toyota’s A3? Can they do this regularly, say to the tune of 10-20 every year? If they cannot, then there is a need for a standard or for the person to be replaced.

it’s a vary nice website