The flexible assembly line at Toyota is a well-known manufacturing approach. Such a flexibility gives Toyota the ability to produce different models in almost any sequence. These lines were already common at Toyota around 1990, and by now they are found at many car makers. Time to take a look at how it is done and why it is good.

The flexible assembly line at Toyota is a well-known manufacturing approach. Such a flexibility gives Toyota the ability to produce different models in almost any sequence. These lines were already common at Toyota around 1990, and by now they are found at many car makers. Time to take a look at how it is done and why it is good.

Introduction

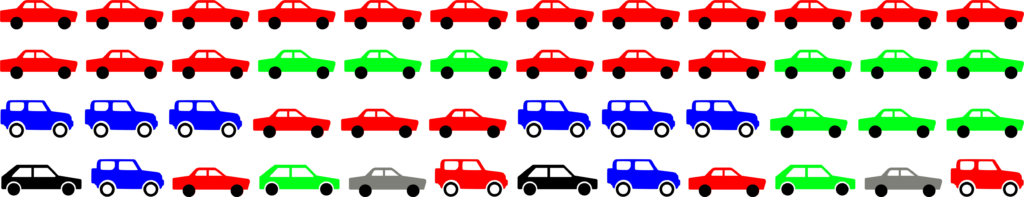

Flexible assembly lines commonly refer to lines with the ability to make different products at the same time. In automotive, the most famous company known for its flexible assembly lines is Toyota, which already in 1990 had multiple such flexible assembly lines. Nowadays there is rarely a car plant that does not (claim to) have flexible assembly lines.

For example, the Daimler Factory 56—at the time of writing one of the most modern automotive lines—produces its most luxurious S class car and Maybach (basically an S class with a different name) with combustion engines, hybrid engines, and fully electrical engines on the same assembly lines. Many quite different power plants on the same assembly line!

On a side note, please do not confuse this with flexibility in the line layout. This is (very confusingly) also called a flexible assembly line at Toyota. Read more about this on my blog post.

What Does Flexible Mean?

But let’s start with the basics. What does “flexible assembly line” actually mean? There are plenty of companies with wildly different flavors of flexible lines that all claim to be flexible. For them, having a “flexible assembly line” merely means the line is more flexible than before… which is good, as it is a step in the right direction. Yet from a lean point of view, not all of them would be considered flexible, at least not by me.

Let’s approach this from the opposite of what would be an inflexible line. Such a line makes one variant of one product only, and would need time for a changeover before switching to another product. For me, the first requirement for a flexible assembly line would be that the changeover time from one product to the next would be zero. Or, more precisely, practically zero. In other words, the changeover is fast enough that it can be done without losing any capacity on the assembly line. As soon as a product has to wait or capacity on the line is lost, it is no longer a flexible assembly line. This was the easy part for an flexible assembly line.

The next question is more difficult. How different do the products have to be for an assembly line to be rightfully considered flexible? There is, unfortunately, no clear answer, but varying shades of flexibility. For example, if the cars produced on an assembly line differ only by the color of the seat and are otherwise identical, I would not consider it to be flexible. If it would be different models, then it would be flexible. However, for example, the Daimler Factory 56 mentioned above makes both S class and Maybach models… which is nothing more than a longer, more luxurious S class. Hence, different names may not be technically so different, after all. To give an extreme example, the Czech Kolin plant makes the Toyota Aygo, the Peugeot 108, and the Citroën C1 on the same assembly line, since these are technically the same cars with different exteriors.

On the other hand, I would not expect the same line to make both fridges and cars. Hence, I would consider larger differences in the product necessary to be considered a flexible assembly line. Daimler Factory 56 assembling different power trains (combustion, hybrid, electric) for the S-class and the Maybach would be a flexible line for me, as would be the Czech Kolin plant. But this still has a lot of wiggle room…

Also, on a side note, the discussion is usually on a flexible assembly line, but I would extend this generally to a flexible production line, regardless if it is assembly, machining, or any other type of production process.

How to Become (More) Flexible

The primary goal for a flexible assembly line is to get the changeover times low enough that they do not interfere with normal production flow anymore (often simply called a changeover time of zero). This can be achieved basically by having the tool match the product. Either the tool is generic and can fit any product on the line, or the product has generic features and all products can fit the one tool, or a combination thereof.

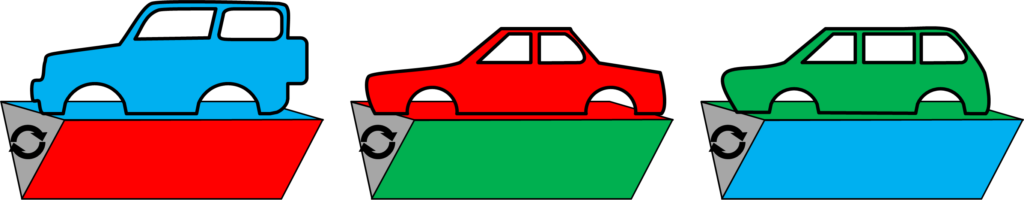

An example from Toyota for a tool that can fit multiple products is a triangular workpiece holder/carrier. This is simply a triangular structure that rotates so the top matches the product as illustrated below. Side note: This is an example where the changeover time is not zero (the tool needs a few seconds to rotate), but it is fast enough so that it does not hamper the flow of the products.

An example of a product that has been designed with tool flexibility is the “Modularer Querbaukasten” (MQB) at Volkswagen. This is an auto body design that allows different wheelbases and car lengths while having similar parts that can be attached by similar tools. Volkswagen uses this for around forty models. Many other car makers have similar concepts (Mazda is particularly admired for this within Japan).

There are many more possibilities. In some cases it requires hardware changes, in others you merely have to adapt the software. If human workers are involved, do not forget to train them, though.

Why It Is Good to Be Flexible

This flexibility—if used correctly—has many advantages. By having multiple products or product categories on the same line, you can use the capacity for different products. Hence, if one product is having a slump and another a peak in demand, the flexible line can simply make more of one than the other. This flexibility allows you to better meet the needs of the customer. For example, in old times a model at Toyota was profitable if they sold 20 000 per year. Nowadays, using even more flexibility, it can be profitable from 5000 vehicles per year. Although, both of the above you could also do with a batch production that has changeovers.

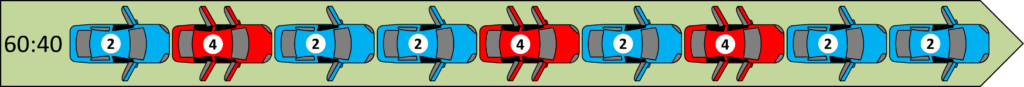

But what you can do only in a flexible assembly line is mixed model sequencing. This is a complex topic, hence I wrote a twelve-post series on Mixed Model Sequencing. For example, if you have a two-door and a four-door model, you sequence them at equal intervals so that the door assembly station does not get over- or underworked.

Smaller lot sizes also help you to reduce inventory and lead time. As a flexible assembly line can do lot size one, it can have a large positive impact on the inventory and the lead time. Overall, this flexibility can reduce manufacturing cost by producing more efficiently, allow faster adaption to changes in demand, and also reduce lead times. Now, go out, make your system flexible, and organize your industry!

Christoph, excellent post as usual and very informative. When we started the Toyota Georgetown KY site flexibility was limited to having a station wagon every four vehicles because the interior required an additional four minutes. The advances since 1988 have been substantial and in Toyota fashion, this has been the result of continuous improvement with well tested processes. Walk before running has always reduces risk. Tesla tried to run when starting production in the former NUMMI facility and had 25% productivity compared to the joint venture performance for several years. Quality and reliability still lag industry averages.

The flexible assembly line at Toyota sounds a lot like a Reconfigurable Manufacturing System, coined by prof. Korean in 1999. If you have more of these type of cases, they would for sure be interesting to read about

Hi Bjørn, Toyota used such flexible assembly lines long before 1999. Also, when googling for “Reconfigurable Manufacturing System”, the first link claims that it was “Originally developed by the University of Michigan College of Engineering’s Research Center”.