In this post I will look at how the tractor maker Fendt handles variability in its plant in Marktoberdorf, Germany. In my view, Fendt is one of the benchmark plants in the world in handling variability. In my previous post I looked at reasons why you may (or may not) leave one part empty on an assembly line with a part normally at every fixed interval. In this post I would like to expand on the idea of playing with the distance between parts to handle such variations in the cycle time, but with a focus on assembly lines where the interval between products can vary. We will look at how Fendt uses this to wrangle its variability.

In this post I will look at how the tractor maker Fendt handles variability in its plant in Marktoberdorf, Germany. In my view, Fendt is one of the benchmark plants in the world in handling variability. In my previous post I looked at reasons why you may (or may not) leave one part empty on an assembly line with a part normally at every fixed interval. In this post I would like to expand on the idea of playing with the distance between parts to handle such variations in the cycle time, but with a focus on assembly lines where the interval between products can vary. We will look at how Fendt uses this to wrangle its variability.

Fendt

Fendt is a German maker of agricultural machines, and part of the AGCO corporation. The company was founded in 1930, and has now around 7500 employees in around five locations in Germany. In 2023 they produced a record number of 21.794 tractors in Marktoberdorf.

Fendt is a German maker of agricultural machines, and part of the AGCO corporation. The company was founded in 1930, and has now around 7500 employees in around five locations in Germany. In 2023 they produced a record number of 21.794 tractors in Marktoberdorf.

The parent company AGCO made a revenue of 14,4 billion US-dollar in 2023. As tractors a needed for operating equipment like a plough, seeder or loader wagons they have to be highly compatible with various implements from Fendt as well as other manufacturers. These implements are needed to do the different agricultural work over a planting and harvesting season.I recently had the opportunity to visit their main plant in Marktoberdorf and see firsthand their rather unique approach to manage variability.

The Challenge of Variability at Fendt

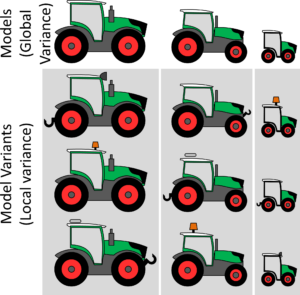

The Fendt Plant in Marktoberdorf produces tractors. Their challenge is that they have to produce eleven different models (currently—the number is likely to go up). Each model also has multiple variants. At Fendt, they call the variance between different models their “global variance” and the variance within one model their “local variance.”

The Fendt Plant in Marktoberdorf produces tractors. Their challenge is that they have to produce eleven different models (currently—the number is likely to go up). Each model also has multiple variants. At Fendt, they call the variance between different models their “global variance” and the variance within one model their “local variance.”

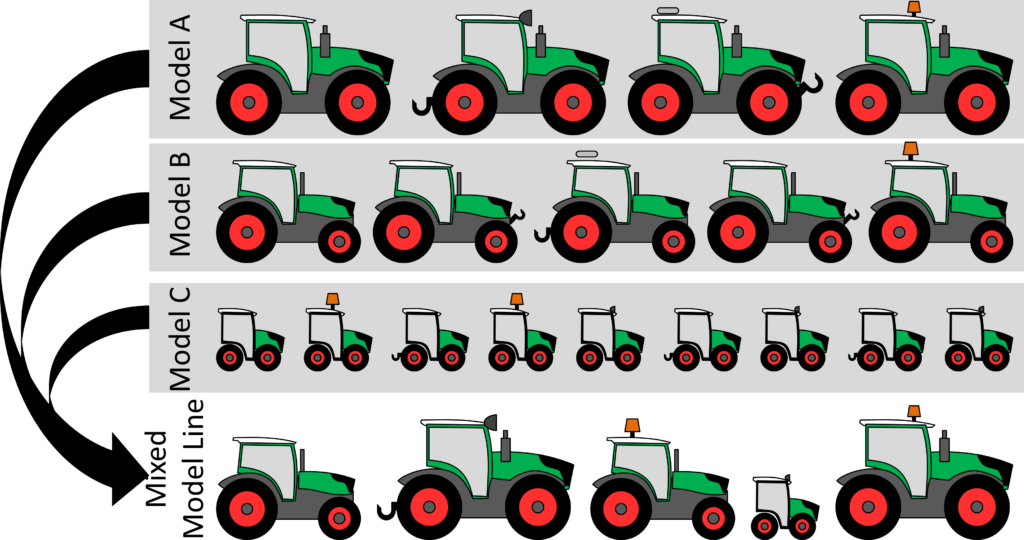

Challenges with mixed models and their different work content are nothing new. One possibility is to use sequencing, having a high-workload product followed by a low-workload product, so on average it is manageable. I have written about before in a (rather long) series of posts on mixed model sequencing.

However, the variation for tractors is significantly larger than for cars. While cars are all somewhat similar in size, size can vary widely for tractors. The smallest tractor is a cute little thingy barely over 1 meter wide that you could drive in your front yard, whereas their biggest machines are 517 PS monsters designed to farm Texas. And they are assembled on the same line. This leads to vastly different work content for the assembly line. The main factors that influence these fluctuations in work content are engine power, length, width, and weight. At Fendt, there was also the clear management decision that “Variance has to be mastered, not reduced.” With tractors, there is no “one size fits all” approach.

Normally, such differences in workload would require different assembly lines. After all, a car maker does not make bikes, cars, and trucks on the same line… which is actually a reasonable analogy in terms of size and complexity. Unfortunately, the quantity produced does not justify separate assembly lines, and all products run on the same line.

In sum, Fendt has a product variability that is significantly greater than what most other companies experience on the same assembly line. The “usual tools” just did not cut it for Fendt, and they tackled this problem in their own way.

Solution: Adjust Distance

That is where they decided to use the distance between products to change the takt time. On a continuously moving line, the distance between one product and the next is the equivalent of the time available to work on the product at one station. If there is a large distance, there is more time until the next product needs to be worked on. If there is a small distance, there is less time. Luckily for Fendt, they already changed to an assembly line using AGVs when they introduced a new model earlier. These AGVs are also adjustable, and can extend for larger models and shrink again for smaller models. They simply programmed the AGVs to keep a certain distance from the next product, and set this distance depending on the product type. Side note: When I say they simply programmed… it is never that simple, and it is still a lot of work to change the software. For example, the AGV speeds up at fire doors so they can be closed quickly in an emergency, and then it slows down again.

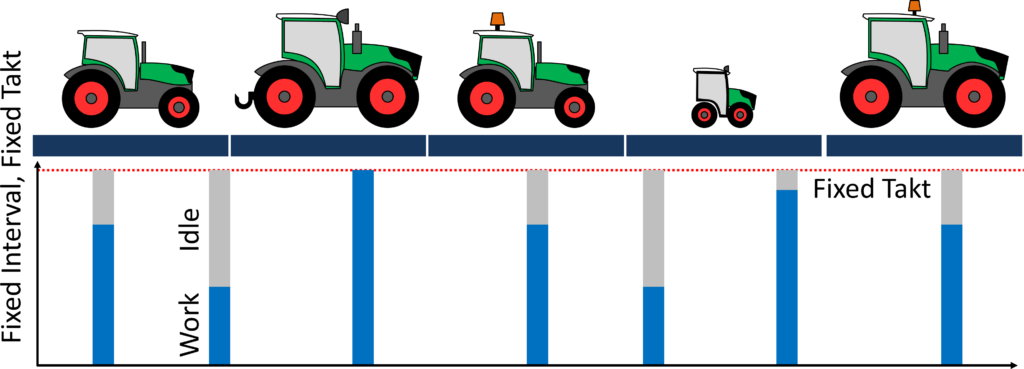

Anyway, if you would have all products at the same distance (as is common in most continuously moving assembly lines), every product gets the same time (i.e., they all have the same takt time). While you can play a bit by having a high-workload product followed by a low-workload product so that the operators can catch up, the variation at Fendt was just too much. Below is an illustration of the takt time and the wasted idle time if all products are the same distance (i.e., fixed interval, fixed takt).

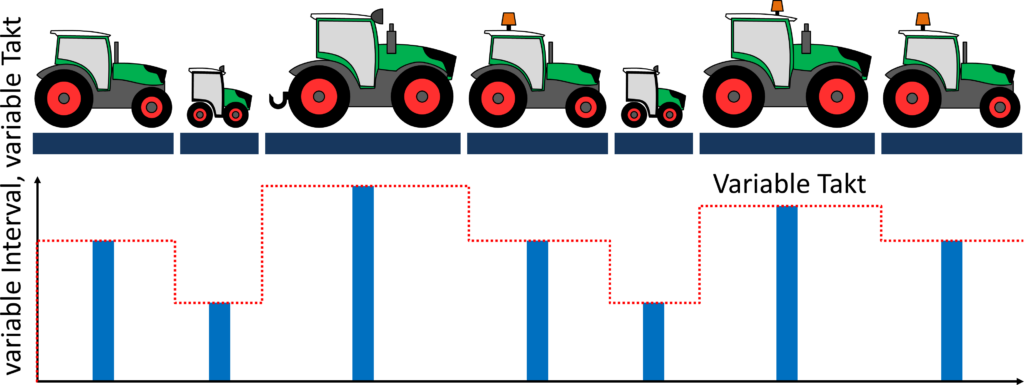

As mentioned above, Fendt plays with the distance between their products on the assembly line through the control of their AGVs. Their average distance between products is 7.5 meters, but the shortest is 6.75 meters and the longest is 9.86 meters. This gives the different products effectively the ability to adjust the takt time between 90% (6.75 meters) and 130% (9.86 meters). This roughly corresponds to the total workload for the different tractor models. Hence, smaller products that need less time to do the work get less time, whereas larger products receive more time. Below is an illustration for such an variable interval, variable takt assembly line. They can also adust the speed of the assembly line, but usually run at an average takt of slightly over five minutes.

Fine Tuning

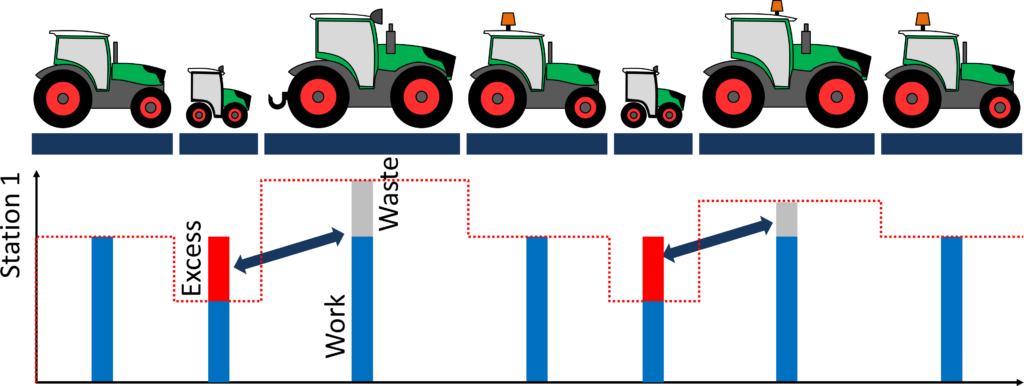

However, the graph above is oversimplified. While larger tractors require on average more work, this is unfortunately not evenly distributed. Some stations may indeed have more work, whereas other may have less, or at least not quite as much. It is unlikely that one takt for one product (i.e., one distance) will fit all stations along the line.

Here, Fendt has also developed quite a few solutions, including sequencing the products that for most stations a product that has not enough time (i.e., excess workload) is followed by a product that has too much time (i.e., idle time), as illustrated below. But this is only one out of a few approaches they have done to manage variability.

But this I will discuss in more detail in my next post. Now, go out, look at the sources of your fluctuations in your manufacturing system, wrangle them, and organize your industry!

Source

The primary book on variable takt is Bebersdorf, Peter, and Arnd Huchzermeier. Variable Takt Principle: Mastering Variance with Limitless Product Individualization. ISBN 978-3-030-87169-7, Springer, 2022. (also available in German) Many thanks to Mr. Bebersdorf for explaining me his approach.

PS: Thanks to Jonathan Folberth for showing me Fendt, and to Peter Bebersdorf for explaining variable takt!

Martin Hofmann 😎

Very innovative application of pull production. Looking forward to your next post on the topic.

Hello, I was wondering if Fendt uses AGVs for their entire line or if, for example, for the final ones where the wheels have already been installed the tractors are put on their wheels and moved using another type of conveyor (like roller or slat platforms), and also how this choice would eventually impact the flexibility of the overall line

Hello Luca, the tractors are on AGVs for most of the time (including the assembly of the drivetrains beforehand, albeit these are separate AGVs. Only at the very end they are on their own wheels, shortly before the testing stations.