Toyota is (among other things) famous for its team structure on the front line. They have a quite low ratio of team members to supervisors, and I believe that is part of their success. Whereas many Western companies overstuff their hierarchy, at Toyota supervisors actually have the time to help their people and to also improve the operations. Let me dig deeper into that. This blog post was inspired by the new book by Baudin and Netland, Introduction to Manufacturing.

Toyota is (among other things) famous for its team structure on the front line. They have a quite low ratio of team members to supervisors, and I believe that is part of their success. Whereas many Western companies overstuff their hierarchy, at Toyota supervisors actually have the time to help their people and to also improve the operations. Let me dig deeper into that. This blog post was inspired by the new book by Baudin and Netland, Introduction to Manufacturing.

Team Structure at Toyota

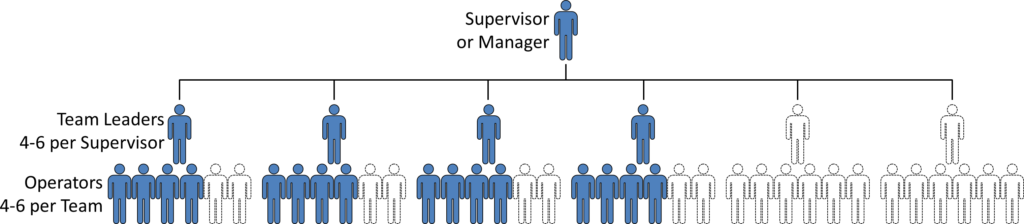

At Toyota, front-line operators are structured into teams of four to six operators (Other sources say five to eight, but my own observations tend toward the lower number). These teams are led by a team leader, called hancho (班長 for squad leader; group leader; team leader), although nowadays at Toyota the English word team leader is also sometimes used. Usually, this team leader is promoted from the operators, and is a highly experienced operator who knows the workstations assigned to the team very well. This position is somewhat a transition between operator and leadership. The team leader does not have the authority to take disciplinary action, and his work usually also includes actual operations in addition to leadership. A team leader works 40 to 60% of the time on actual production tasks, and the remaining time on supervision.

At Toyota, front-line operators are structured into teams of four to six operators (Other sources say five to eight, but my own observations tend toward the lower number). These teams are led by a team leader, called hancho (班長 for squad leader; group leader; team leader), although nowadays at Toyota the English word team leader is also sometimes used. Usually, this team leader is promoted from the operators, and is a highly experienced operator who knows the workstations assigned to the team very well. This position is somewhat a transition between operator and leadership. The team leader does not have the authority to take disciplinary action, and his work usually also includes actual operations in addition to leadership. A team leader works 40 to 60% of the time on actual production tasks, and the remaining time on supervision.

Besides actual production work, the team leader is there to support the operators. They assist operators if there is a problem, which may be indicated by the andon line. This includes problems on safety, time (a worker falling behind), and quality (product not good), although since at Toyota a defective product is usually not allowed to move forward, a quality problem quickly becomes a time problem. In any case, the team leader helps. For bigger problems, support by the supervisor or maintenance should also arrive shorty. Team leaders should make sure that material and tools are available and in working order. If an operator needs a break (e.g., for the bathroom), the team leader will take over.

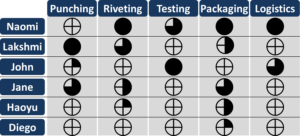

Team leaders also keep track of qualifications and training needs, for example using a skills matrix (or qualification matrix). They are able to train operators on the job, helping new operators until the newbie can do the job on their own. They verify that people follow the standards, and are the first contact for ideas on how to improve the standard. They also take an active role when implementing improvements.

Team leaders also facilitates communication within the team, upward, and to adjacent teams, also across shifts. They track performance and adherence to standards, and do the twice-yearly performance review of the operators. They are also active if a changeover should be necessary (although many lines at Toyota are flexible enough to switch products without a changeover).

Above the team leader is a group leader (a supervisor or manager, no longer an operator), who is in charge of four to six team leaders and their teams. Hence, a supervisor is in charge of sixteen to thirty-six people, although usually at the lower end. The average is around eighteen people. Please note that the names team leader, group leader, supervisor, etc. are used and defined very differently across different companies.

Benefits of the Team Structure

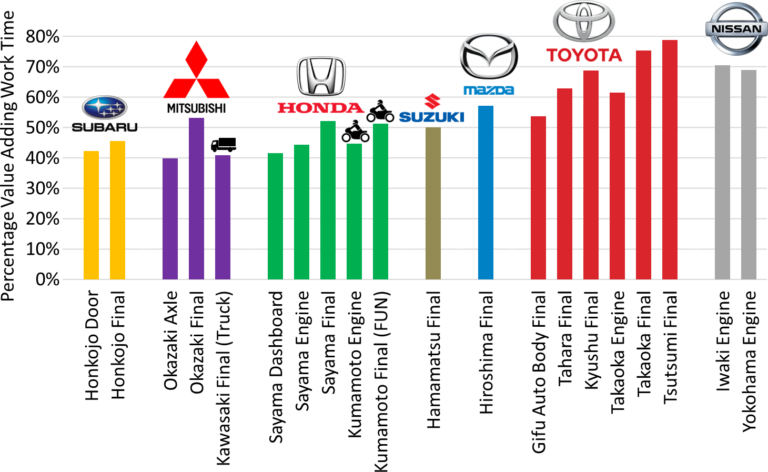

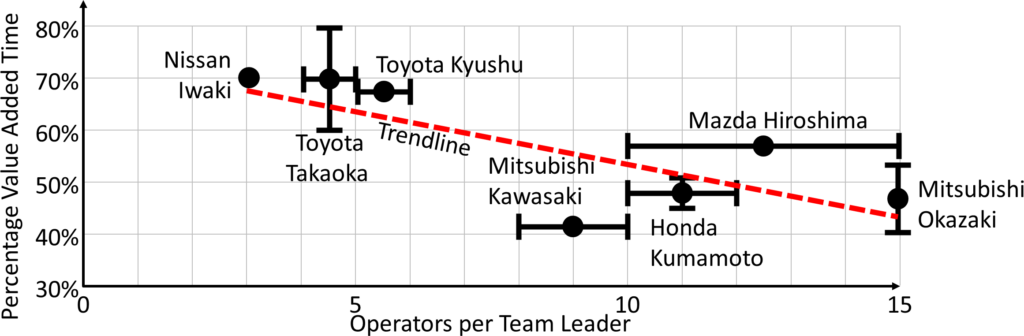

The question is, is this all worth it? Is it worth having extra workers to create small teams in order to better support the front-line worker? Toyota thinks it is (and I agree). Luckily, I have data! A few years ago I did a Grand Tour of Japanese Automotive. As part of this, I measured the percentage of the time a worker adds value at an assembly line. I also asked some of the plants of their ratio of supervisors to front-line managers.

Even back then I noticed a correlation between smaller teams and better performance, but I never put that into a chart. Now I did. Below is the relation of the percentage value add with respect to the team size of different automotive plants (and one truck plant) in Japan. I also added a trend line.

Be aware that the data is a bit messy. For example, I measured only one line at Mazda Hiroshima, with 57% efficiency. Mazda also gave me a wide range of ten to fifteen operators per team leader. Mitsubishi Okazaki told me that they had fifteen team members per team leader, and I measured two lines, the axle assembly at 40% and the final assembly at 53%. The percentage value add is a rough estimate of mine, and the team size is as told by the plant, hence both measures are a bit wobbly. Still, there is a clear correlation with smaller team sizes having much better performance. Very roughly, every reduction of team size by one adds approximately two percentage points of value adding time. (Note: Please don’t mix up reducing team size by firing people; that is something different.)

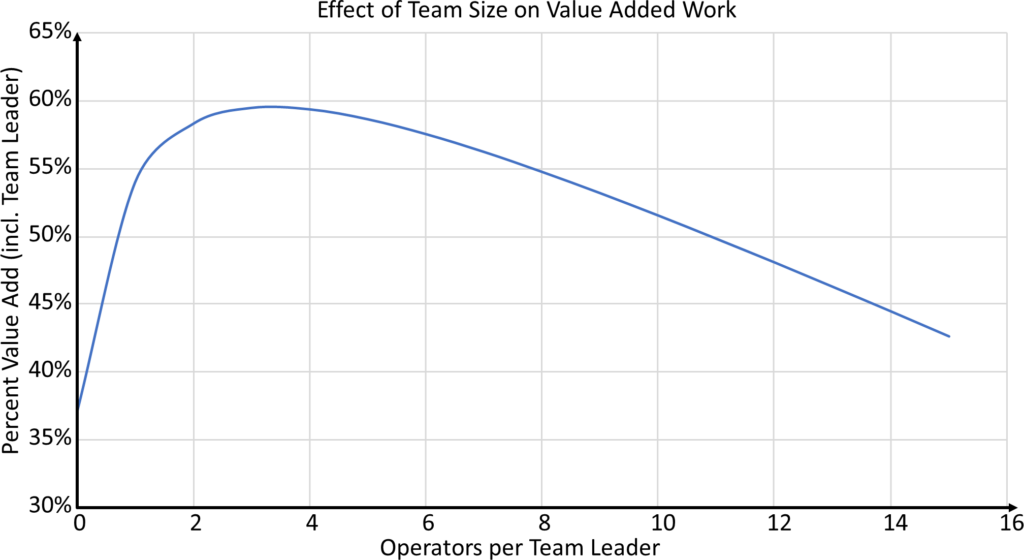

Let’s continue the number crunching. If you have fifteen operators for each team leader, then there are teams of sixteen people including team leader, or 6.3% of your people are team leaders. If a team leader works productively only 50% of the time, you have 3.1% of the people (half of 6.3%) doing overhead, and 96.9% actually working on the product. Your value add is 44%, so effectively 43% of the time of all your people is generating a benefit for your company (96.6% working at 44% efficiency).

If you have ten operators for each team leader (i.e., teams of eleven including the team leader), then 9.1% of your people are team leaders, or 4.5.% of the time of your people is overhead, with 95.5% of the time working in the product. However, the percentage value add has increased to 55%, and effectively 52% of the time of your people is generating a benefit for your company. Plotting this for any team size between fifteen and zero (all people are team leaders) gives the following overall value added work. Based on these estimations, the ideal team size is somewhere between two and six people, just where Toyota has its team sizes.

Please be aware that this is only a rough estimate, with lots of assumptions. The data is not very precise (a confidence interval would be all over the place), I made a linear extrapolation beyond the rage of my data (i.e., team sizes below three), I assumed that a team leader costs the same as a operator, and so on. On the other hand, I doubt that a team leader of fifteen people will still be able to work 50% of his time on the product. But overall, it seems to be worth the effort to make smaller team sizes of around two to six operators per team leader. On a side note, in projects it is also recommended to have team sizes of three to six people for ideal performance.

Why Don’t We Do That in the West?

So why don’t we do this in Western companies? The answer is – as all to often in lean – accounting. The cost of a supervisor or team leader can be measured very well. The benefit is really hard to nail down. If accounting cannot measure it, it sets it to zero (i.e., a team leader has no value for accounting). Hence, to improve the numbers, team leaders got reduced and we often find team sizes of twenty, thirty, and even more operators for a single supervisor or team leader.

So why don’t we do this in Western companies? The answer is – as all to often in lean – accounting. The cost of a supervisor or team leader can be measured very well. The benefit is really hard to nail down. If accounting cannot measure it, it sets it to zero (i.e., a team leader has no value for accounting). Hence, to improve the numbers, team leaders got reduced and we often find team sizes of twenty, thirty, and even more operators for a single supervisor or team leader.

Naturally, the team leader is totally overwhelmed with work, and can barely make ends meet, let alone properly help his operators or support improvement. Hence, efficiency goes down and the whole operation suffers.

Reversing this is difficult, since you would have to add team leaders, which cost money, but it takes some time before the benefit of smaller teams is realized (another example of the valley of tears in lean). However, in the long run, it would be quite worthwhile. Now, go out, reduce your team size and get your operators the support they need, and organize your industry!

Source for some data and the inspiration

I was inspired to write this blog post by the excellent book by Michel Baudin and Torbjörn Netland, where they discuss the team structure on page 17. I added my own data to theirs to create this post, but the entire book is recommended reading 🙂

Baudin, Michel, and Torbjørn Netland. 2022. Introduction to Manufacturing: An Industrial Engineering and Management Perspective. 1st edition. New York, NY: Routledge.

very good reading thanks !

we hear often about “autonomous teams” or “cross-functional teams” in several industries where someone from production and from other support function (methods, Q, SC…) meet on daily basis to solve issues and talk about KPIs…

Would you recommend a team leader for this task or rather for the manager (of the team leaders)?

Thanks in advance!

BR

Your observation on “why we don’t do that in the West” is totally on target. To meet aggressive cost controls, we tend to staff with very high spans of control, resulting in the team lead or supervisor feeling like a “hamster on a treadmill.” Additionally, those individuals are often inundated with non-value added administrative work that limits their ability to hang at the Gemba.

Hi Christoph,

Good info here… And in the section pertaining to why the West does not follow a similar tact in using a low leader to worker ratio to improve value-added-time performance, the answer – you highlight the reason as being that it has everything to do with overarching GAAP protocols. As such, that reason begs the larger question of whether or not the traditional/mandated method of tracking a business’ performance does not actually create a barrier to the implementing LEAN BEST PRACTICES ala the combination of the TPS/WAY?

As a footnote… it certainly has struck me over the years (decades) that this is the case and that attempting to do anything close to what Toyota is capable of doing is akin to the Sysiphean scenario/punishment of having to push a boulder up a hill… only to have it roll back down again once it reaches the top. This phenomenon essential remains unresolvable without dealing with its root cause(s). And as such, it makes for a good environment for continuously selling/promoting various [incomplete] aspects of Lean THINKING AND BEHAVING… but NEVER the whole enchilada as in TRUE LEAN THINKING AND BEHAVING ala the combination of TPS/WAY.

Bottom line: Here’s the $64/fly-in-the-ointment question… Realistically speaking/thinking, is pursuing TRUE LEAN THINKING AND BEHAVING actually a lost cause in the West (i.e., any company subject to following GAAP) or is doing the “FAKE” Lean thing (i.e., using a piecemeal approach) actually adding more VALUE (for customers) than is being WASTED in TIME/EFFORT (for company employees)?

An excellent post covering a vital topic.

The Toyota system is founded upon the “family”. The team leader does all of the things mentioned, acting in the role of “0lder Sibling” to the team. Hence no ability to discipline formally, only to explain and convince. The Cummicho or Group Leader is the parent figure.

This allows much freedom of communication and has the ability to treat individuals as people, rather than simply as assets. It also provides a sense of belonging to the team member, even on an organisation of thousands.

For more information please see “The Balance Of Excellence” available as paperback or ebook from Amazon world-wide.

Good post covering a unique concept

Small Teams do prove to be beneficial to a company. A team Leader is as good as his/her desire to perform the role they applied for. As a former team leader, I took pride in my opportunity to make our work as efficient as possible. This required establishing relationships with key personnel in my support network (maintenance, quality, safety, and union).

With a unified support network in place, a lot can be accomplished at the floor level supporting jidoka (Built in Quality). If any link in this support chain breaks, it can take you back to firefighting daily just to make production. So, make your choice and good luck

Very interesting article regarding Team Structure. I’m working in the Trucks/Construction Machine Industry and we have identified the Team size as a trigger for improvement.

The Team size is very important but the way Toyota works with the small Team is much more important for me : They are deeply involved in their process (I can say they own their process) and they have the autonomy to improve it and to try new ideas. In our western companies, most of the time, improvement are performed by manufacturing engineers. We think our People are involved, but we only ask them their feedback and it is definitively not involvement. Another important point is the way the support functions collaborate with the front line : most of the time, operators are skilled enough to take decision (maintenance, quality, ..) and the support function are there to bring expertise and to train and develop the People.