Everybody in lean talks about flow. You have to create flow! In particular you have to create one-piece flow. However, while this is true, I often find a lot of confusion on what flow means. Time for a post that goes to the basics and looks at what exactly flow is. My next post takes this up one step by looking at what one piece flow is.

Everybody in lean talks about flow. You have to create flow! In particular you have to create one-piece flow. However, while this is true, I often find a lot of confusion on what flow means. Time for a post that goes to the basics and looks at what exactly flow is. My next post takes this up one step by looking at what one piece flow is.

What Is Flow?

Let’s start with the easy part. What is flow? In particular, what is flow in manufacturing? In its most basic form, flow refers to the movement of parts. The opposite is parts standing still. Hence, you want to get your parts moving. To be more precise, you don’t just want them to move around randomly, but move in the direction of the value stream. Otherwise you could just put your entire plant on a ship and drive in circles, but that is not the point.

In reality, at any given time, at least some of your parts are standing still. For one, you may need to stop parts for the actual processing. While there are moving assembly lines, you may also have processes that are in one spot, for example a milling machine. Customarily, parts that have stopped for processing are not counted against your flow. If it is a batch process like a heat treatment or a drying process, there may be a lot of parts that are standing still but are being processed for a long time.

But you surely also have plenty of parts that are neither moving nor processing. Your warehouse is full of not-moving parts. And, if you are any typical company, these not-moving parts outnumber by far the moving or processed parts. In sum, flow tries to reduce this share of idle parts and hence also to reduce the lead time. This is very closely connected to the reduction of inventory. Inventory is usually needed to buffer fluctuations, hence the main lever is to reduce fluctuations to reduce the inventory. Beware. This sounds a lot easier than it is. So overall, flow aims to reduce idle inventory and to increase the share of parts in transport or in processing.

How Much Flow?

So, how much flow do you want? This is also easy only in theory. The true north of flow is 100% in processing or in transport. Just in Time and Ship to Line are common lean methods that improve flow by having less parts idle and more being handled or processed. At the same time, like most true north visions, 100% flow is not possible. You probably always have some products idling.

There is also no agreed on goal for what percentage of the parts should be flowing. In many factories, my guess would be that in excess of 95% or even 99% of the parts are idle at any given time. In this case, even getting it down to 90% would already be an improvement. The goal, simply, is to become better. Whatever your flow rate is, your target should be a higher flow rate.

There is also no agreed on goal for what percentage of the parts should be flowing. In many factories, my guess would be that in excess of 95% or even 99% of the parts are idle at any given time. In this case, even getting it down to 90% would already be an improvement. The goal, simply, is to become better. Whatever your flow rate is, your target should be a higher flow rate.

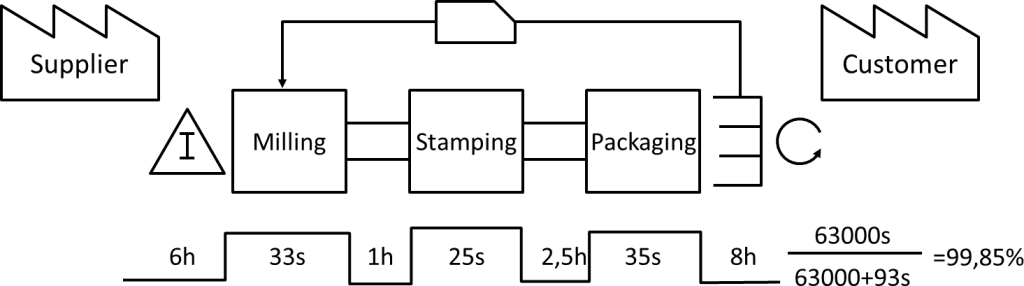

At the same time, I do not know of any plant that actually measures this flow rate. The closest thing I know is on value streams where the percentage of time a part is processed versus the entire lead time could be plotted. The simple value stream map below has a up/down line at the bottom, where the processing times and the waiting times for a typical part are added. Here, the part waits for around 6 hours in the inbound warehouse, before being milled for 33 seconds, before waiting another hour for 25 seconds of stamping.

Overall, the part is not processed for 99.85%, and only 0.15% of the time there is processing, which is hopefully also adding value. Hence, the percentage of value added time is only 0.15%. Such low numbers of value-added time is typical in many factories, and even 99.99% not value add or more is quite possible. This percentage is a close approximation of the flow, or lack thereof. But do note that these idle times do include transport, which would be part of flow. Yet, for me it makes no sense to also include the transport times, since transport by default is waste.

Hence, improving flow is more of a philosophy than a metric, and if you want a measurable KPI, the percentage of value-added time is a much better measurement than the percentage of “flow” time.

Cheating Flow?

Just for the record, the transport of the parts should also be at normal speeds. If you slow your transports down, your share of goods in progress will increase. This would follow the letter but not the spirit of material flow.

Similarly, if you offshore your factories, a lot of parts would be on the ship moving for months toward the customer. While this numerically would improve the flow, it would also increase the lead time, which is just the opposite of what lean wants you to do.

What to Flow?

So, in general, you want to improve flow, or – more precisely – improve the percentage value add. The ultimate but unobtainable vision is 100% value add. It takes a constant effort to merely not become worse, let alone to become better. You simply do not have enough time to improve everything. So, where should you start?

As always, you should start where you get the biggest bang for the buck. Flow reduces inventory and hence also lead time. What parts give you the biggest benefit for reducing inventory? Usually, these are the expensive parts due to their tied-up capital, the large parts due to their storage cost (and related parts that require special storage conditions like refrigeration or climate control), and parts that expire quickly. As for the lead time, this is often critical for make-to-order final products. Depending on your factory, you may have some additional factors to include. This compares with the effort to reduce inventory, which is probably harder to estimate. Again, start with the part that gives you the best benefit for your effort. Don’t optimize your inventory of O rings for 2 cents each while the expensive engine blocks are piling up.

So, in sum, creating flow is in reality improving the percentage of value added time by reducing inventory, and you should start improving this with your expensive and large end products. The idea of parts actually moving (flowing) is more of a visual metaphor to highlight your parts idling in your warehouse. In my next post I will move the concept of flow one step further and explain the idea of one-piece flow. You surely have heard of this, but there is still a lot of confusion on the idea. Now, go out, get your material flowing (or at least less sitting around), and organize your industry!

Hi Chris,

A topic that has always interested me a lot. I agree partially that it is philosophical. I do think, however, that it ís important to understand also what is more exactly meant when speaking of “flow”. As a clear definition helps identify obstacles to flow, and -inversely- measures to improve flow. I also think it is important as so many “methods” claim to be improving flow, or claim to be better at it than other approaches (just think of DBR, S-DBR, JIT, DDMRP, MRP, …). When working as SC director at Valeo, my single strategy slide only said “create flow” and sites were in need of a better understanding of what exactly it meant. I was in need of a “yardstick” to measure flow that aligned with the philosophical intent of the word “flow” in a process context.

It was the reason why I further developed this topic in three blog posts in 2017:

https://thejitcompany.com/perfect-flow-1/

https://thejitcompany.com/perfect-flow-2/

https://thejitcompany.com/perfect-flow-3/

Look forward to your feedback on these posts.

Hi Chris,

Yes, asking “what is flow” is an important question that’s worthwhile addressing. However, like so many aspects related to the principles, practices, and concepts of TRUE LEAN THINKING AND BEHAVING (ala the combination of TPS/Toyota WAY), the CONTEXT in which any question about those practices, practices, and concepts is being asked and answered is even more important. Without a specified CONTEXT, the meaning being conveyed is often incomplete and potentially misleading. More specifically, whenever these sorts of questions are approached from a deterministic or reductionist POV, what’s often not conveyed is the relationships (i.e., interactions and interdependencies) that exist between the topic of interest (e.g., process FLOW) and ALL the other critical elements of a SYSTEM that need to be taken into consideration.

That said, this blog posting on the topic of “what is flow” seems to be neglecting the bigger (i.e.,more HOLISTIC/SYSTEMIC) CONTEXT in which “flow” related issues can and do occur. More specifically, “what is flow” and “why it is such a critical element in an overall production SYSTEM” is very closely related/tied to and integrated with the other critical elements comprising the OVERALL SYSTEM. And those other elements characteristically take the form of: 1) what constitutes VALUE (as perceived by customers/consumers), 2) WHAT IS THE PROCESS FOR CREATING AND DELIVERING VALUE (while at the same time generating as little waste as possible in the process), 3) what does FLOW have to do with maximizing the value being added and minimizing the waste, 4) how does flow relate to customer/consumer DEMAND and its variability, and 5) why is there a need for CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT/PERFECTION (aka ON-GOING PROBLEM-SOLVING) related to that process flow.

Without addressing these other essential HOLISTIC/SYSTEMIC considerations and thereby limiting one’s answer to a mere/simply technical description of the key characteristics of FLOW by itself carries the strong potential for conveying/promoting a reductionistic mindset; one which is antithetical to the practice of TRUE LEAN THINKING AND BEHAVING.

Bottom line: Yes, excessive inventory levels are problematic to an efficient and effective process flow. But, more importantly, ensuring that VALUE is being maximized and delivered in line with customer/consumer needs and expectations encompasses a wider range of TRUE LEAN THINKING AND BEHAVING capabilities that, if not recognized and addressed, will likely impede the pursuit and realization of world class operational (i.e., systemic) excellence.

This was a fascinating post. It was interesting how you said flow was more of a philosophy than a metric. The amount of value-added activities within the flow is the metric that is important to look at where process improvement is needed. I liked how you also included how continuous improvement for process flow is necessary not only to become better but also not to become worse. This is also how businesses can stay competitive within industries because if they aren’t progressing they are degressing.