Product variants drive up cost. The more variants you have for the same quantity sold, the higher your production cost. Inversely, if you can reduce your number of variants, you can reduce your cost. In this post I will give you some general suggestions on how to reduce your number of variants. Hopefully these inspire and help you to become more efficient.

Product variants drive up cost. The more variants you have for the same quantity sold, the higher your production cost. Inversely, if you can reduce your number of variants, you can reduce your cost. In this post I will give you some general suggestions on how to reduce your number of variants. Hopefully these inspire and help you to become more efficient.

Why Variants Are Bad

Variants increase complexity. The more product variants you have, the more parts you need to obtain or make, track, and keep on stock. Overall, this increases your inventory. It also increases your fluctuations. The sales of two products at half the quantity will fluctuate proportionally more than one product with full quantity. Ten products at one-tenth the quantity will fluctuate even more. The impact of these fluctuations are often not well understood in industry, but they cause a lot of trouble, most significantly the risk of running out of parts, but also the risk of excess stock. Also, making a part very seldom requires more effort by the workers to remember how to make it, more effort to set up the tools, etc. It is an economy of scale, where a low-volume product is much more expensive than a high-volume product. Hence, the number of variants are a major cost driver for manufacturing and logistics.

Variants increase complexity. The more product variants you have, the more parts you need to obtain or make, track, and keep on stock. Overall, this increases your inventory. It also increases your fluctuations. The sales of two products at half the quantity will fluctuate proportionally more than one product with full quantity. Ten products at one-tenth the quantity will fluctuate even more. The impact of these fluctuations are often not well understood in industry, but they cause a lot of trouble, most significantly the risk of running out of parts, but also the risk of excess stock. Also, making a part very seldom requires more effort by the workers to remember how to make it, more effort to set up the tools, etc. It is an economy of scale, where a low-volume product is much more expensive than a high-volume product. Hence, the number of variants are a major cost driver for manufacturing and logistics.

Why Variants Are Necessary

On the other hand, variants are necessary. It is rare that a company has only a single product and all customers will be happy with the same product you provide. One example would be tap water. You get one type of water, and the the water supply company does not give you an option of low-chalk or sparkling tap water. Another example would be if the supplier has immense power over the customer, and for example in former East Germany the Trabant car had very few options, yet people were still waiting on average for seventeen years to get one.

On the other hand, variants are necessary. It is rare that a company has only a single product and all customers will be happy with the same product you provide. One example would be tap water. You get one type of water, and the the water supply company does not give you an option of low-chalk or sparkling tap water. Another example would be if the supplier has immense power over the customer, and for example in former East Germany the Trabant car had very few options, yet people were still waiting on average for seventeen years to get one.

But most companies have variants simply because the customer wants them. Having slightly different products attracts more customers and/or more market segments, and overall provides more sales. Hence, the number of variants are a major driver for sales.

A Trade-Off?

The first obvious direction is a trade-off. Is the cost of producing a variant worth the sales? Or, more generally, does the sale cover the cost, is there a profit? It sounds like an easy solution to do the math for every product, and keep those that make a buck. Unfortunately, we run into a common problem again with lean manufacturing. It is very easy to calculate the revenue from a sale. It is much harder to calculate the cost of making the product. Especially the impact of fluctuations are nearly impossible to pin down financially. Thus, cost accounting often ends up with a revenue that exceeds the (far-underestimated) costs. It does not help that the cost data may be outdated and from times when the product was selling well and had significant economies of scale. Overall, manufacturing is often losing the trade-off with sales due to the inability to measure fluctuation costs.

The first obvious direction is a trade-off. Is the cost of producing a variant worth the sales? Or, more generally, does the sale cover the cost, is there a profit? It sounds like an easy solution to do the math for every product, and keep those that make a buck. Unfortunately, we run into a common problem again with lean manufacturing. It is very easy to calculate the revenue from a sale. It is much harder to calculate the cost of making the product. Especially the impact of fluctuations are nearly impossible to pin down financially. Thus, cost accounting often ends up with a revenue that exceeds the (far-underestimated) costs. It does not help that the cost data may be outdated and from times when the product was selling well and had significant economies of scale. Overall, manufacturing is often losing the trade-off with sales due to the inability to measure fluctuation costs.

How to Reduce Variants

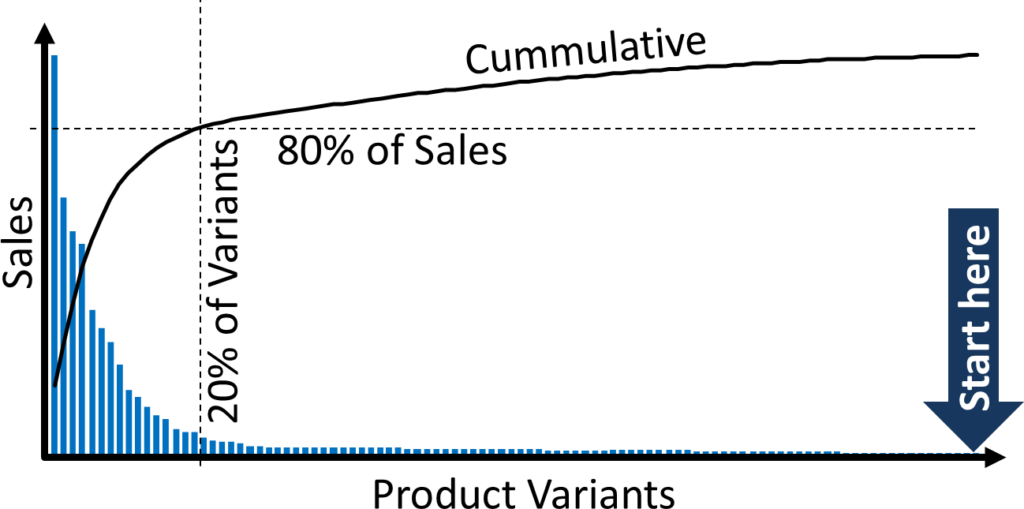

Reducing variants requires you to look at every product you sell and determine whether making it is still worth the effort. This is a slow process and requires time and determination. Don’t start this analysis with the high runners—these you are likely to keep. Instead start with the products that sell the least—those have the best chances of being eliminated. Below you see a bar plot of 100 (fictions) products with their sales quantity, sorted from the best selling to the slowest selling product. The line is the cumulative number of sales (different scale). You probably have seen similar plots before, these Pareto diagrams are famous, and you will probably find that 80% of your sales are from roughly 20% of your products.

Hence, start looking at the least-selling products first. Can you eliminate these? Such low-selling products are often either failed products, products at the end of their life cycle, or the result of previous bad product decisions.

This will in all likelihood always be a battle with sales, which is measured on how much they sell. As mentioned above, they have the advantage that the revenue can be measured much easier than the cost. But, assuming there is a neutral discussion (yes, I know, I am an optimist), then the revenue generated should be compared to the cost, including an estimation of the additional cost from fluctuations and a lack of economy of scale. This gives you an idea whether the product is viable on its own.

However, you rarely sell only independent products. You probably have a family of similar products. The question is, what will the customer do if the product is no longer available? Is it a lost sale, or will the customer switch to an alternative similar product from your product line-up? Unfortunately, here you have even less reliable data than for the standalone cost-benefit analysis. Nobody really knows what the customer will do until after the fact. You may end up with manufacturing arguing that there are plenty of good alternatives, while sales argues equally enthusiastically that the customer will never ever come back. It is a tough, gut-based decision.

However, you rarely sell only independent products. You probably have a family of similar products. The question is, what will the customer do if the product is no longer available? Is it a lost sale, or will the customer switch to an alternative similar product from your product line-up? Unfortunately, here you have even less reliable data than for the standalone cost-benefit analysis. Nobody really knows what the customer will do until after the fact. You may end up with manufacturing arguing that there are plenty of good alternatives, while sales argues equally enthusiastically that the customer will never ever come back. It is a tough, gut-based decision.

Additionally there may be other considerations. Do you have a major customer who insists on this product? I once had such a case where a major customer infrequently also wanted to buy a very exotic product. In fact, he was the only one who occasionally bought this exotic product. Yet, the customer insisted on having this product and threatened to switch to a competitor if it was no longer available. In this case, it makes sense to keep on producing. Or, more generally, are there external factors that require this product? Besides a customer, having this product may also be required due to government regulations, contractual obligations, or simply as a way to annoy your competitor.

Additionally there may be other considerations. Do you have a major customer who insists on this product? I once had such a case where a major customer infrequently also wanted to buy a very exotic product. In fact, he was the only one who occasionally bought this exotic product. Yet, the customer insisted on having this product and threatened to switch to a competitor if it was no longer available. In this case, it makes sense to keep on producing. Or, more generally, are there external factors that require this product? Besides a customer, having this product may also be required due to government regulations, contractual obligations, or simply as a way to annoy your competitor.

Overall, deciding on which product to ax and which one to keep is a tough question. In my next post I will also look at the related question of how to reduce the part variants that go into products. Now, go out, ax your most inefficient and slow-selling products, and organize your industry!

Classic Problem for many companys. I just wanted to add a little side note. If you have customers – like mentioned above – that expect custom made goods try to extract this variant out of the main flow. Henjiunka is a great tool but has its limits – sometimes it is cheaper to create a new line rather than force a “bad” product into a good adjusted product mix.

Great post on product variants. I like how you talked about how some product variants are necessary for customer satisfaction. You posed good questions to ask to see if product variants are really necessary. I feel many companies have problems with carrying too many of the same or similar products, which can hurt them in the long run.